Berkshire Bach Ensemble's

A 15-year-old Berkshire tradition moves to Colonial Theatre

By: Michael Miller - Jan 05, 2007

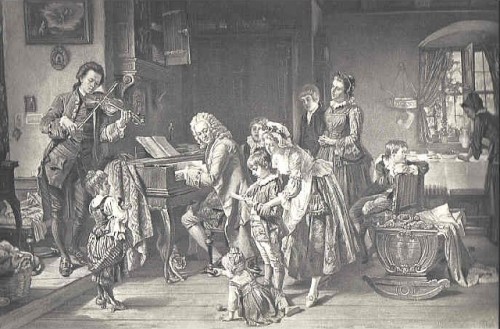

A few months ago, reviewing a Williams faculty concert which combined Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart with examples of the music enjoyed in places like Williamstown in the early nineteenth century, I was fascinated by the abyss between the two cultures. The crudeness and churchiness of the American songs demonstrated that there existed absolutely no context in the former English colonies for the sociable music of the Europeans. I could imagine Beethoven's harmless Septet with its rambunctious (but eminently salonfähig) energy conjuring up the spirit of some diabolical orgy, or at least something like the effect of Le Sacre du Printemps at its first performance. As abstract and spiritual as it can be, music is a fundamentally social art. It cannot thrive without people who take pleasure in gathering for occasions calling for works like Beethoven's Septet, Mozart's Masonic Singspiel, a Brahms symphony, or masses by Palestrina, Byrd, Verdi, or Stravinsky.The Berkshire Bach Ensemble's performance of J. S. Bach's Brandenburg Concertos under the direction of Kenneth Cooper at the Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield was all about context. The theater is new—as everybody knows, splendidly restored after years of disuse, but the BBS New Year's Concert is an established tradition, now in its fifteenth iteration. Monday afternoon, when many television screens were a-dance with football, the Colonial's spacious lobby was filled with a festive crowd, among which I saw many familiar faces. I sensed general delight with the renovation and anticipation of the music to come. This would appear to be just the sort of human situation Mr. Cooper was there to create. As he said in his program notes to an earlier New Year's Concert, "Bach, as we are well aware, was part of a large, 'extended' family, which met every year for music and good company. Bach's house, according to his son Philipp Emanuel, was 'like a beehive,' swarming with people, open to all. We at Berkshire Bach love this image and feel that we all are now members of Bach's global, very extended family."

The newly resurrected theater can't have hosted a more salutary event, since Bach's beloved, perhaps excessively familiar music, Cooper's warmth and enthusiasm, and the gusto of his mostly outstanding players transformed it into a thoroughly homey sort of place—maybe to a fault, since at least one family with small children seemed a bit too much at home for their neighbors, who were there, after all, like the rest of us, to listen to Bach. In any case, it looks as if the Brandenburgs at the Colonial is already on its way to becoming a holiday tradition—and a welcome one at that.

The acoustics of the Colonial Theatre, as heard from my seat roughly in the middle of the floor, were excellent for this music. The balance was perfect in an ambiance which was free of any excessive reverberation, verging on dry in fact (but pleasantly so), and all of the instruments came through as they should. I could see that the mixing desk was manned, but I could hear no trace of amplification, which would have been entirely inappropriate. I made an inquiry and learned that light amplification was used in the parts of the balcony because of some dead spots, but none in the main hall. (Hint: spring for good seats at the Colonial.) Built in 1903 as a legitimate theater, it is a first-rate venue for small classical performance groups, and I hope the management will make the most of it—and resist any temptatation to use any electronic enhancements.

The older tradition of the BBS performances themselves creates a safe environment, one in which personal quirks and experimentation can flourish unscathed, and Mr. Cooper is thoroughly at home with it. I am new to these concerts, and my comments will reflect issues which old-timers will have come to terms with years ago, but I'll make them anyway in the hopes that anyone who hasn't yet gotten into the habit or anyone who has gotten a little bored with the Brandenburgs will come next year and refresh their listening habits.

"Our version," as Mr. Cooper calls it, is unusual, remembering even that the Brandenburgs are familiar to many people through Wendy Carlos' synthesizer or Dave Brubeck's jazz arrangements, to name only two alternate "takes" on Bach's score. What is most remarkable is that his liberties, however challenging they may seem, derive from performance practices current in Bach's own time. Manuscripts with alternate notes and instrumentation exist from Bach's pupils and sons, and not a few of these variants appear to have been occasioned by causes as mundane as the availability or lack of a particular instrument and a competent player. Modern conservatories teach Baroque ornamentation fairly routinely. However, it is Mr. Cooper's way to take a scholarly hint and run with it as far as he can. The results are great fun and a revelation of the spirit of Bach's music, however self-indulgent or irritating they may occasionally prove to be. After all the foundations of Bach's music are as robust as its surface, and, like Shakespeare's plays, it can easily survive a substantial amount of benevolent abuse.

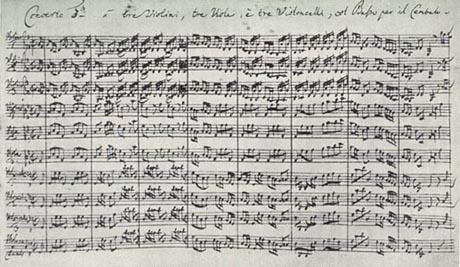

One of the most notable features of Bach's set of concerti in the Italian style is the variety of their instrumentation. Each concerto relies on several instruments combined in different ways, and the instrumentation of each concerto is strikingly diverse. When, in his formal dedication to the Margrave of Brandenburg, Bach referred to them as "Concerts, que j'ai accommodés àplusiers Instruments," he meant it in a significant, if ambiguous way. Malcolm Boyd has observed that it can mean both that there is a variety of different instruments, both string and wind, and—most innovatively!—keyboard, and that the concerti are to be played by several—not many—instruments, with fluid transitions from solo to ripieno. Overall the twenty-one musicians (including Mr. Cooper) comprising the Berkshire Bach Ensemble were enough to allow for some doubling of string parts when desired. Modern instruments were combined with some some period instruments. Soloists stood, while ripieno musicians sat, occasionally merging their musical roles, following Bach's interweavings. Mr. Cooper basically hove to fairly deliberate tempi with marked accents and rests. There were some intonation problems in the earlier part of the concert, which diminished by the third concerto and only reappeared in the viola parts of the sixth, but on the whole the playing of most, particularly as soloists, was truly impressive.

In Bach's first concerto, a variety of instruments join in solos without any one of them assuming dominance, that is, oboe, bassoon, two hunting horns, and "violino piccolo." The last of these, a miniature violin of higher pitch than standard, is not always easy to find, and modern performers often stay with the conventional instrument. Here it was done with a vengeance, since the soloist, Deborah Buck, who played superbly, used a large-sounding, dark-toned modern violin, which sounded like some sort of super-Guarneri. (In fact the instrument was made by the late nineteenth century maker, Vincenzo Postigliano, who often copied Guarneri instruments.) Her contribution, replete with extensive ornament and that of the fine wind soloists were a particularly attractive part of this performance, which otherwise included the most daring and least successful of Mr. Cooper's manipulations of Bach's scoring. A part for tympani was added, following Bach's own rearrangement of the third movement of this concerto for Cantata no. 207, as well as a tambourine and cymbal in the dance movement with which Bach decided to conclude the work—which is odd enough in itself—as well as further variations and additions. Works like this were often used in Bach's time as preludes to vocal works, and in fact a version of this one was used in this way. However, in its setting in the Brandenburgs, it functions as the prelude to an interlude—an extended dance movement as long as any two of the others—in "our" version, that is. Mr. Cooper considers this to be "country music," a fitting conceit for our particular region, and this would justify the added percussion. It was fun to listen to, and it was really the interpolation of the tympani which undermined the overall effect, since it was just too distracting, at least as it was executed. (But let's not forget that Bach did in fact combine tympani and horns on occasion, most notably in the cantata BWV 143, "Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele.") In his decisions Mr. Cooper was of course following Bach's lead, but it was also sagacious of him to lay down his strongest challenge first.

The second concerto, with Bach's bizarre and wonderful solo group of recorder, the rare clarino trumpet, oboe and bassoon, was less tempting to Mr. Cooper's imagination—beyond a wealth of ornament—and was neatly played. The trumpet disaster in the first movement was easily forgivable in view of the fiendish difficulty of the instrument, often sidestepped in performance by substituting a standard trumpet, a horn, or even a sopranino saxophone. In the third Mr. Cooper's gave his imagination more scope by adding wind parts, following Bach's adaptation of the first movement as an introductory sinfonia for his Cantata no. 174 of 1729, but expanding them radically to fill the entire concerto. The second movement of this concerto consists of only a two chord cadence, an invitation to improvisation, but rather than improvise like most contemporary players, Cooper has substituted Bach's sinfonia in e minor, the seventh of his three-part keyboard inventions, and it sounded particularly beautiful in his arrangement, with prominent oboe solos, eloquently played by Meg Owens and Martha Heller. In the fourth Marjorie Bagley's solo was particularly impressive. She managed the ornament with aplomb and showed a remarkable fluency in shifting back and forth between expository passages and virtuoso interludes, as well as in her interactions with the splendid recorder solists, Allison Hale and Judith Mendenhall. The fifth with its revolutionary keyboard part put Mr. Cooper in the role of soloist, together with Judith Mendenhall playing the traverse flute and Patrick Wood, violin. He played the great cadenza-like solo brilliantly, calling forth a well-deserved round of applause which lasted pretty much through the final ritornello and caught fire again after the final cadence. The sixth brings us back to a sonic world somewhat like the third (as written in Bach's 1721 manuscript, at least). It is scored for strings alone with violins omitted, one cello, two viole da gamba, and bass. With Mr. Cooper setting a broadish tempo, BBS regular Liuh-Wen Ting played most expressively in her lead viola part, and in spite of the wandering intonation the final concerto was as compelling as the others.

Taken as a whole this reading of the Brandenburgs was festive and enjoyable, Mr. Cooper's alterations were founded on precedents in Bach's own reuse of the material, and for the most part the ornamentation was in the proper style and attractively played. What is there to object to, really? Or, better, what issue arises from this interpretation, which after fourteen years must be considered a mature one? This interpretation follows a course of its own, not only in its extensive ornament and rescoring, but in its pragmatic combination of period and modern instruments. (It's worth noting that performances by mainstream symphony orchestras entirely on modern instruments have become something of a rarity.) Mr. Cooper's rationale lies in Bach's constant adaptation of his earlier work, as he reused it later in different contexts. It does the public no harm to enter into Bach's creative process—or compositional practice—in this way, but we must remember that the "Brandenburg Concertos," as we know them, owe their existence to the finished manuscript Bach specially copied for presentation in 1721. He specifies instrumentation precisely, and even if we have difficulty interpreting indications referring to obsolete instruments today, no one has ever suggested that Bach's instrumentation is not successful as he set it down on that occasion. In fact a deeper rationale has been discovered for almost every compositional decision Bach made in these pieces. One recent writer has even found political and metaphysical dimensions in the scoring and structure presented by the 1721 manuscript.

What this document represents is a thoroughly thought out collection of concertos and movements that Bach had composed and performed during his period of employment by Prince Leopold at Cöthen, beginning in 1717, and probably even earlier, when he was at Weimar. He was most likely hoping the Margrave of Brandenburg would offer him a better job, but he was also following a pattern he repeated several times during his career of synthesizing a systematic compilation of a body of work he had done. Some have observed that, after making the grand summa, he tended to lose interest in the form and moved on to something else. When we find later rearrangements of movements of the Brandenburgs they appear in cantatas, a more substantial form than the concerto, which continued to be in demand through the remainder of his career at Leipzig (1723-50). However the later manuscript copies of the Brandenburgs by his pupils suggest that he continued to perform the concerti with his family and friends at home and possibly in public in later years, always adapting the score for specific occasions and groups, which in the 1721 version included his patron. This "afterlife" is the context on which Kenneth Cooper builds his concept of the concerti.

The Brandenburgs are so familiar today, mostly through recordings, that it is hard to imagine that they were for many years forgotten, and after their rediscovery in 1850, they remained "homeless" for almost as many years. Performers and audiences, doubtless put off by the difficulties of translating their instrumentation into contemporary performance practices, failed to share the enthusiasm of the musicologist who discovered the famous manuscript. As Mr. Cooper himself has said, the Brandenburgs belong to the twentieth century. Interest in the music did not pick up until the neo-classical 1920's, and a series of recordings in the 1930's made them familiar to a larger audience, particularly that of the Busch Chamber Orchestra. Several of the major conductors of the period performed them with full or only slightly reduced orchestra, particulary conductors who had special affinities with contemporary music, for example Furtwängler, Klemperer, Mengelberg, and Koussevitzky, who recorded them all with the Boston Symphony and whose interpretations were particularly admired. Historically informed performances did not begin to appear until the 1950's and remained rare until the 1970's. The idea of performing them as chamber music, with only one instrument per part and only occasional doubling, which seems almost inevitable today, as it does in the BBS performances, did not take root until even later.

These imaginative performances show that Bach's compositions are as versatile as their creator and can make themselves at home in many places. As much as I treasure what "authentic" performances like those of Hogwood, Pinnock, and Pickett have opened up for me, I feel free to go back to Furtwängler's third, brilliantly performed by the full strings of the Berlin Philharmonic, or his own inspired performance on the piano of the "cadenza" in the fourth.

By the way, a recording of the Berkshire Bach Ensemble's 1999 Brandenburgs is available on their website.

http://www.homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

michaeljames48@gmail.com