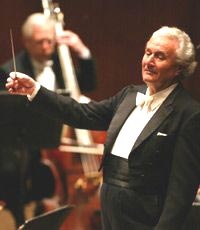

Sir Colin Davis Conducts Vaughn Williams and Beethoven with the BSO

A Rare Performance of Vaughn Williams's Sixth Symphony and Beethoven's Familiar Pastoral

By: Michael Miller - Jan 28, 2007

Boston Symphony Orchestra,Symphony Hall, Boston, January 26, 2007

Sir Colin Davis, Conductor

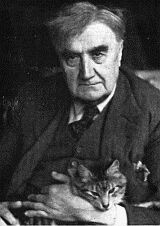

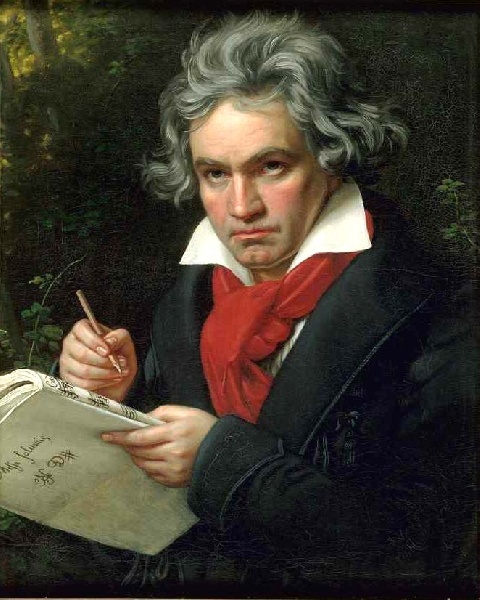

Ralph Vaughn Williams, Symphony No. 6 in E minor (1944-48); Beethoven, Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, "Pastoral" (1807-08)

In his second concert this season, Sir Colin Davis has interestingly paired two symphonies with particular relations to programmatic content. Beethoven's "Pastoral" Symphony, one of the most familiar in the repertory, is the quintessential program symphony. Its connection with experiences in nature were established by the composer's own written indications, and the direct musical references to country sounds—bird calls, a rushing brook, a peasant band, etc.—are obvious enough. On the other hand, Sir Ralph Vaughn Williams found it necessary to discourage programmatic interpretations of his Sixth Symphony, which he began in 1944. Life was grim in Britain at the time of its first performance in April 1948. The memory of the Second World War was still fresh. Ruins lay all about London. Rationing was still very much in force. Britain was nearly bankrupt, and the Cold War was well underway. The Sixth Symphony reflected that mood sufficiently for one reviewer to call it the "War Symphony." Visions of nuclear holocaust were seen in the bleak final movement, which is tonally ambiguous and pianissimo throughout. Vaughn Williams said to a friend: "It never seems to occur to people that a man might just want to write a piece of music." On the other hand, his audiences perhaps cannot be too severely blamed, since he had written programmatic symphonies in the past, including a "Sea" symphony and a "London" symphony. Eventually, in 1956, he came out with a textual background for the last movement at least, when he wrote to a friend: "...I do not believe in meanings and mottoes, as you know, but I think we can get in words nearest to the substance of my last movement in 'We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our life is rounded with a sleep,'" quoting Prospero's farewell in Shakespeare's "The Tempest," which he set for chorus with similar music.

Hearing Vaughn Williams' Sixth today, I believe modern audiences will most immediately admire its taut construction, not only in the structure of the four movements, but in the thematic interrelationships and pointed orchestration, not to mention the way in which the movements dovetail into one another without pause. During his long lifetime Vaughn Williams had developed a strong association with lyrical countrified moods (not unrelated to those of Beethoven's "Pastoral") and British folk music, and, although he had made large and even harsh statements earlier in his career, audiences seemed to crave an explanation for "aberrations" like his Fourth and Sixth Symphonies. Today it is not so difficult to approach it as absolute music, when it is performed—which isn't terribly often in this country, or certainly with the BSO, who played its American premiere at Tanglewood in August 1948 under Serge Koussevitzky. As harsh and forbidding as the symphony was thought to be, it was very popular, receiving many performances over the next few years in Britain. Koussevitzky took it on tour through the winter of 1948/49 in at least a half-dozen cities, but that was the last BSO performance until 1964, when Sir John Barbirolli conducted it. Sir Colin Davis conducted the next and last performance of the work in 1982. Hence his return to the work this week is a welcome rarity.

Sir Colin's rapport with the orchestra was, if anything, even stronger by this second weekend, and he made the most of the disciplined ensemble, extreme dynamics, and subtle colorations the orchestra can now produce. He was able to use contrasts in string sonorities to bring out a great range of detail in inner voices without impeding the rhythm and flow of the music. In fact he kept an energetic, forward-moving pulse throughout. Vaughn Williams included a saxophone in his scoring, and the inevitable jazz rhythms make an appearance at points in the work, but not so obviously connected with the saxophone, reminding us that this kind of subtle fusion of musical genres was not invented by Mark Antony Turnage. When the wild saxophone solo, splendidly played here, breaks out in the third movement, we have had plenty of time to absorb the musical idioms of the symphony, and the effect can make its expressive point to the full. His reading of the last movement had a perfect balance of contrapuntal texture, movement, and an otherwordly mood blending dread and release.

If anyone came to the concert thinking Vaughn Williams is old hat, Sir Colin easily disabused of them of it. What's more, at eighty he clearly has no interest in the elegiac or valedictory posture some even younger musicians indulge in. His approach was energetic, alert, and nuanced.

The same could equally apply to his interpretation of Beethoven's Sixth. Mercifully free from any of the clichés which beset this almost over-performed work, Sir Colin encompassed all its beauties of melody, flow, mass, intimacy, and contrast.

In the program notes Jan Swafford made the interesting point that in planning a pastoral symphony Beethoven was taking on a difficult task. The incorporation of folk motifs, the imitation of natural sounds and peasant instruments, the pastoral mood, often maintained by siciliana rhythms, had all been heavily exploited by composers of all nations. While such music had its place in the taste of the Esterhazy court, Josef Haydn struggled ingeniously to keep the genre alive, usually with success. Beethoven, as he himself wrote, was so deeply attached to the country, and country walks with his musical sketchbook were so deeply ingrained in him, that his deep personal connection with nature enabled him to bring it off. He avoided the usual clichés by supporting his allusions to pastoral motifs by giving them melodic, harmonic, and textural value all at once, as in the bird-song trio at the end of the second movement, or in the rustic chordal patterns which blend into the orchestral texture as a whole. Often these qualities can be heard more easily in a period instrument performance, but a good conuctor will bring them across on modern instruments as well. However, as Beethoven's symphony found its prominent place in the repertoire and the years went by, it created its own clichés in performance. As a result I have heard some conductors approach it with condescension.

There was absolutely none of that in Sir Colin's interpretation. He is able to take immediate pleasure in the spirit of the music and the rightness of Beethoven's composition. His opening was robust, but lyrical. The opening dialoguing phrases in the first and second violins were crisply phrased and muscularly shaped, forming a strong contrast with the flowing chords in the lower strings. This detail and the tension of the dialogue of the different voices separating and coming back together set the tone for the rest of the performance. While Sir Colin's tutti were massive and bright, his attention to contrasting string and wind tone enabled a wealth of inner detail to be heard. I'll mention only one further detail, which I've never heard the like of. Shortly past the mid-point of the second movement (E in the score), the "Scene at the Brook," Sir Colin brought the orchestra down to a breathtaking pianissimo with an only moderate slowing of the tempo, which nonetheless conveyed a momentary sense of complete stasis and peace, but the flow and textural color of the strings remained intact. The final bars of the last movement had much the same delicacy, bringing to a close a fully-realized performance of the "Pastoral" and leaving us in no doubt of its greatness.

*

Anyone interested in what the "Pastoral" sounded like for earlier generations should listen to Pristine Audio's new release of a beautifully restored performance by Bruno Walter leading the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1946. His interpretation of this work in particular was greatly admired over decades and is very much worth hearing today.

Contact information for Michael Miller

http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

email: michaeljames48@gmail.com