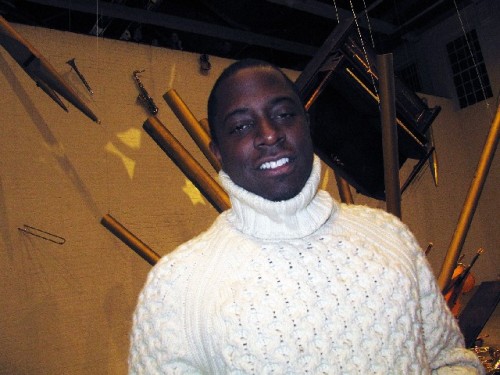

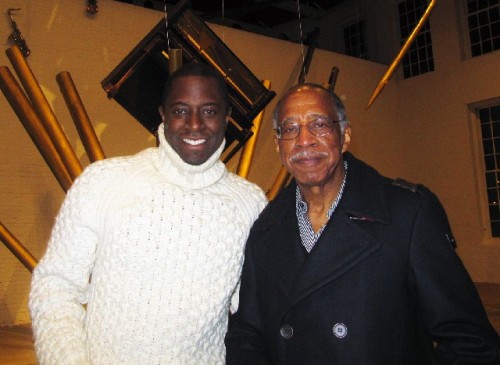

Sanford Biggers at Mass Moca

The Cartographer's Conundrum Explores Afro-futurism

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 05, 2012

Building Five of Mass MoCA is one of the largest and most daunting spaces for contemporary artists in North America.

In the decade plus since the former Sprague Electric campus in North Adams was converted into a contemporary art museum there have been basically two approaches to a space that is approximately the length of two football fields and two stories high. The second floor the length of the building was removed to create a soaring vertical space flanked on both sides by two parallel rows of enormous clerestory windows. When the building functioned as a factory workers toiled from dawn to dusk primarily by natural light.

At the far end of the gallery enough of the former second floor remains to form a broad balcony, with a gallery below, that serves to display works of art as well as look down at the length of the interior from another dramatic vantage point.

Although the panes of glass are transparent the interior evokes the feeling of standing in the nave of Chartres Cathedral. But in a structure intended to worship commerce rather than God. In America those disparate notions are too often conflated.

In dealing with this vast setting artists opt for an approach that either the glass is half empty or the glass is half full. The primary tendencies are to fill the space with an enormous installation or quantity of monumental elements, or to leave it bare, allowing the space itself to be an entity of what is contained. At times there is the feeling that the space has been wasted and underexploited. Left too barren.

Then we are nudged by that time tested axiom “Less is More.” Or, as with rapier wit, Tom Wolf postulated in his book From Bauhaus to Our House “Less Is More Less Is A Bore.”

The current installation by Sanford Biggers The Cartographer's Conundrum strikes one as neither half empty nor half full. Perhaps for visitors it will be just right. It is uncluttered enough to evoke minimalism. There is a lot of breathing room and aesthetically charged air around the disparately scattered objects. But not that many that we surrender cognizance of the resonance of the space itself as an activator of the visual and emotional experience.

There is the familiar response evoked by so many Mass MoCA projects “What the fuck is this?”

I like first to walk through the space and absorb the experience. To run it through a data bank of received information and filters for undigested concepts and signifiers. This tips and teeters through the senses like a rapid sequences of Xs and Os hopefully resulting in some kind of graph or print out with definitive conclusions.

I guess that’s another way of saying that we process the work.

Many visitors start with the text applied to the wall next to the stairs that descend into the gallery. Astrid always reads this and often insists on providing clues as to the intentionality of the work.

Either stubbornly or arrogantly I refuse to read labels or text. Art is meant to be looked at first and foremost. That can be so powerful and moving that no further explanation is required. These tend to be the greatest and most profound experiences. The visual contact evokes a set of questions or, as Biggers’s embeds in the title of the exhibition, conundrums.

Conundrums are ok. Some visitors like to plunge into the labyrinth more readily than others. In the center of the maze we might encounter the Minotaur, a monster of self. Or a Gordion Knot of entwined threads of issues and agendas. We have to determine the risk factors of jumping down the rabbit’s hole. Where are the “eat me” and “drink me” essences that allow us to fit into the confined and complex spaces of surreal conflations of fantasy and reality. If it is the artist’s trip and agenda-bat, ball, game and rules- how willing are we to make them our own? Selfishly one might ask “What’s in this for me?” Or “Will I be safe and can I survive the experience?” Is the artist sharing an aspect of humanism that extends understanding of the universe and self? Is the work generous? Is the artist offering something of value to the viewer? Or, is the work arcane, inaccessible, careerist, flatulent and dyspeptic?

The norm of the critical process is to proceed with caution. To gather, compile and sort through visual impressions and shared information. We deliberate and agonize before posting conclusions that might come back to haunt us as shallow and ignorant, insensitive, vulgar or vacant. Pretty Vacant was the line from a Sex Pistols song that always taunted me with its savage veracity.

Like the artist often critics are left with just a few well defined options. To jump in and run with the pack. To function as an insider and collaborator with the conceptual theories. Or draw a line in the sand. Take some kind of adamant position evoking Socratic/ Aristotelian standards in the face of pervasive post conceptualism.

In other words. To zig or zag.

With the performing arts to praise or pan is more obviated. There is the compelling sense of an audience to contend with. The critic experiences the work in the company of others and may absorb or deflect that commonality.

There is a far greater risk factor in approaching and evaluating visual art. It is an experience that we ideally have individually. We crave to be alone with the work and our thoughts. To be one on one and riveted by what we are looking at.

That is often impossible in those big, jam packed, museum exhibitions of the most famous artists. We see the work over the shoulders of others. At times there are log jams around the most famous pieces as visitors stand there and listen to the pap pumped out by the acoustaguides. Again, I refuse to use them. I don’t need the autocratic insights of Philippe de Montabello to tell me about that work of art.

One prefers to discuss the work with like minded friends and colleagues.

As usual we engaged in a dialogue with the chief installer and artist, Richard Criddle. He always has wonderful insights about the process and fabrication of the work. It is the norm to use whatever materials are on hand. To make as much of the work as possible on site. In this case the artist uses mirrored glass stars of varying scale. Previously he had them fabricated in Brooklyn. This would have been both expensive and risky to transport.

During a visit to MoCA to meet with the curator, Denise Markonish, and Criddle who adroitly makes the magic happen, the artist encountered a stash of mirrored glass. The artist wanted about 150 mirrored stars. Criddle commissioned his wife, the stained glass artist Debora Coombs, to make the stars. Ordering more glass MoCA created some 400 stars which are arranged in clusters on the floor throughout the space. Some of these were then shattered by the artist.

In the dark room under the balcony there is a video simultaneously projecting on two floor to ceiling screens. We are presented with a broad vista of the ocean and waves crashing on the beach. The tide is reversed. From this emerges a tall black man with dreadlocks. We perambulated with him through nature as well as ornate interiors. In some sequences he is tricked out like a fay, androgynous, pimpster/ gangsta musician resembling a Rick James, Bootsy Collins or George Clinton in knee high silver boots. There is a matching metallic glaze on his tripped out grooving face. Is this a black Alice in an ersatz Wonderland?

Wrongly, I assumed this to be the artist. Actually not. As Astrid informed me, it helps to read labels, he is a Brazilian born, German friend of the artist.

What follows is a dialogue with the artist.

Charles Giuliano Talk to me about the stars.

Sanford Biggers The stars started with a show in Brooklyn. (A loud crash in the background). Oh oh. That was one of the installers. The stars started in Brooklyn. I don’t know it’s a reference to the cosmos. And it relates to the mural upstairs of my cousin John Biggers (1924-2001) who passed away.

CG Where was he from.

SB South Carolina but he mostly practiced in Texas.

CG Is this an homage?

SB I think of this from the perspective of research about two generations of artists.

CG What do you mean by Afro-futurism?

SB It’s an emerging field of research about the African disapora in a non traditional, non Western, non historical way. It entails alternative histories and African culture. To recontextualize and understand that history. The futurism comes in as a part of that.

CG It involves a lot of theory. How did that evolve?

SB There is a lot of theory involved. It comes from research. A lot of musicians and artists were already espousing these concepts. You can see that and analyze that in their various jargons. If you look at Thelonius Monk and late Coltrane. It becomes about more than the music itself. The process. Sun Ra. Parliament-Funkadelic. Sci Fi writers like Octavia Butler or Sam Delaney. Even Toni Morrison. It’s Sci Fi and weirdish.

CG Particularly Sun Ra. Space is the place.

SB I read an interesting comment by somebody who was talking about Afro-futurism. Think about is as this. What if an alien ship came down to the US and sequestered a bunch of people and started to trade them for money or for objects and sent them back to their planet and made them work as laborers. What does that sound like? The slave trade. So we recontextualize it.

CG So Afro-futurism is diaspora based.

SB It’s diaspora based.

CG How about Créolité (A theory of French West Indian literature , culture, and identity, most fully formulated in Éloge de la créolité (1989) by Jean Bernabé)? Is that an element?

SB Are you Creole?

CG No.

SB You could be.

CG My friend Robert is. From Haiti. He’s here if I can find him. We are involved in a project about Louis Armstrong and early New Orleans music. We are researching and discussing theories of Créolité as it relates to that city and its culture. The project came about because my actor friend John Douglas Thompson is developing a role in a new one man play Satchmo at the Waldorf. So I am spending the winter researching and listening to the jazz of the 1920s and 1930s.

SB Your (African) hat made me think you might be Creole.

CG I ripped it off from Monk actually. In an earlier part of my life I was a jazz critic. How old are you?

SB Forty one.

CG Typically your generation comes into jazz from Miles and Coltrane.

SB Yeah but through my parents I came in from Dizzy and Duke.

CG That’s still a boundary perhaps mid 1950s. Right now I am very involved with exploring the beginnings, the origins of the music. Which other than Armstrong, who is misunderstood, few jazz fans are interested in. What I see in this installation is a confluence of the visual and aural. The prominent use of instruments is a signifier of the importance of music even though we don’t hear anything. Can you discuss how the visual and musical are converging in the work?

SB I actually call this segment of the work (At the end of the space, a set piece in front of the wall. Rather like an altar and organ) A Joyful Noise Unto the Creator.

CG That sounds like The Sacred Music of Duke Ellington.

SB A Joyful Noise Unto the Creator is actually from Coltrane. Then it was done by Galliano.

CG I’m loving talking with an artist about jazz references. It’s a rare experience to share those interests.

SB Jazz informs how I work. In terms of improvisation. Like going through the back lots and store rooms of Mass MoCA and finding things like these church pews. Ok, how many? How can we use them.

CG So is this a riff?

SB It’s all a riff. Like that piano. We were supposed to drop it and smash it. When we hoisted it up I kind of liked the way it looked hanging. It’s such a pregnant pause.

CG How are the instruments being used in all of this?

SB I think it’s like a chorus. They are about to make music. The whole idea here is about is it an explosion? Or implosion? We leave it open for the possibilities of interpretation.

CG Do you own the instruments?

SB They are all donated or borrowed.

CG As I walk through the space it seems we encounter incidents and intervals. In Building Five you can either pack it full or leave it empty. I get the sense that you want us to experience the space disrupted by encounters with clusters of stars and groupings of objects.

SB You’re good.

CG Why am I seeing and experiencing this? Talk about the parts vs. the whole. What kind of fear factor was there for you encountering the empty space?

SB I saw the space when Tim Hawkinson did the Uberorgan.

CG That was half full.

SB I also visited when Inigo ( Manglano-Ovalle Gravity Is a Force to be Reckoned With) created an installtion.

CG Half empty.

SB I had seen the space for years. So strategically I knew how to approach the space. For me, I was interested in the light play. The optimum time to see this show is during the day in sunlight. It’s never going to be seen at this time of night (during the vernissage). It’s going to be closed.

CG Where did you go to school?

SB Morehouse College. (A private, all-male, liberal arts, historically black college located in Atlanta, Georgia. On February 14, 1867, just two years after the American Civil War, the Augusta Institute was founded. In 1913 it was renamed Morehouse College.) From Morehouse I want to the Art Institute of Chicago for my Master’s.

CG What did Morehouse do for you in terms of setting you on the path to becoming an artist?

SB Are you asking me? (surprised) Look at the history here.

CG I mean what kind of art program did Morehouse have as a small liberal arts college?

SB They didn’t have one which is why I had to go to Spelman (a four year women’s liberal arts college in Atlanta) for art classes.

CG What was it like going to a historically black college?

SB It was great to be with like minded people. There were dudes from all over the United States interested in getting an education and hanging out.

CG In the art world you have to be connected. How did you get on the roller coaster?

SB The Art Institute of Chicago. Then I did a Skowhegan residency. I was in the Whitney Biennial. I showed at the Tate.

CG So, you’re heavy duty.

SB I do what I can.

CG Do you have a gallery?

SB No. I’ve been doing all of this without a gallery. But I do have private dealers and two of them are here; Michael Fine and Mary Goldman. They are friends.

CG Talk about the video. I’ve been looking around for the guy in the dreds.

(“…the wanderings of a man in dreadlocks and a red, white and blue suit (played by the magnetic Ricardo Castillo, a Brazilian-born choreographer, clown, stuntman and D.J. who lives in Berlin) as he emerges from ocean waves and, during an odyssey over rural land and through the rooms of a colonial palace, turns into a silver ghost of himself in shiny platform boots and a glam rocker’s outfit.

“With this multidimensional tableau Mr. Biggers puts into play a semiotic carnival whose main elements are dreamlike allegories of African-American experience. His signature sign, the grinning mouth, which also appears on a lightbox suspended high above “Blossom” at the Brooklyn Museum, alludes to the Cheshire Cat from “Alice in Wonderland” as well as to black and blackface minstrels of yore, whose exaggerated smiles were a legacy of slavery, a survival reflex for the radically disempowered in the form of an authority-appeasing mask.” Ken Johnson, New York Times, October 20, 2011)

SB He’s a good friend of mine named Ricardo. I met him on a bus.

CG There’s a gay element here.

SB Uuhhh. It could be that. It’s open to interpretation. It could be transgender. It could be non gender.

CG Isaac Julian did a video shot on Gore Island (in Senegal where slave ships departed for the Middle Passage). He reversed the tide. (As in Bigger’s video.)

SB I didn’t know that about his piece. The first one we did was in Stuttgart Germany. The second one was (unclear because of background noise while transcribing). My next one will be created in Senegal or Ghana or one of the ports in Africa. Ultimately I want to get back to Ethiopia to work with the Coptic Christians.

CG Thanks. As always it makes such a difference when you have the chance to talk with the artist.

MoCA Press Release

The Cartographer's Conundrum is a major multi-disciplinary installation By New York-based artist Sanford Biggers. This new work is inspired by the Houston, Texas based artist, scholar and Afro-futurist John Biggers (1924-2001). A cousin of his subject, Sanford Biggers' goal is to both study and expand the emerging genre of Afro-futurism, which engages science-fiction, cosmology and technology to create a new folklore of the African Diaspora while simultaneously illuminating the underrepresented career of master painter and muralist John Biggers.

Afrofuturism was a phrase coined in 1995 by cultural critic Mark Dery in an essay Black to the Future, where he links the African American use of science and technology to an examination of space, time, race and culture. In this text Dery defines afrofuturism as: "Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th century technocluture - and, more generally, African American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future…" The movement began in earnest in the mid-1950s with musician Sun-Ra, whose music blended science-fiction, mysticism, African culture (with a particular focus on Egypt) and jazz fusion, all of which coalesced in his 1972 film Space in the Place. In 1975 George Clinton formed his bands Parliament and Funkadellic, which took afrofurturism to new often absurdist heights. Today the movement is still strong, encompassing contemporary musicians like Saul Williams, Janelle Monae, OutKast and DJ Spooky along with writers like Paul Beatty, films like the Matrix, Blade and Chronicles of Riddick and visual artists like Sanford Biggers.

This use of afrofuturist imagery and ideologies links both Sanford and John Biggers work. John Biggers began as a mural painter in the genre of social realism - portraying African American life. His work took a shift when in 1957 he won a UNESCO fellowship, becoming one of the first African American artists to travel to Africa. His trip took him to West Africa, and later he traveled to Nigeria and other African countries. This experience had a profound impact on his work, which afterwards took these African themes, merging them with his images of African American life to create allegories about life, spirituality, hope and survival. John Biggers work also touched upon Afrofuturism in his use of sacred and fractal geometries and mystical imagery.

Sanford Biggers had always been inspired by his cousin's work and journey. So, after being awarded a Creative Capital grant in 2008 Sanford Biggers used the opportunity to conceive of a new project that would place him and his cousin side by side. Sanford began by traveling through western Africa along the same route John Biggers followed in the 1950s, meeting with colleagues and family members along the way.

About Sanford Biggers:

A native of Los Angeles, California, and current New York resident, Sanford Biggers uses the study of ethnological objects, popular icons, and the Dadaist tradition to explore cultural and creative syncretism, art history, and politics. An accomplished musician, Biggers often incorporates performative elements into his sculptures and installations, resulting in multilayered works that act as anecdotal vignettes, at once full of wit and clear formal intent.

Biggers has won several awards including: The Creative Time Travel Grant, Creative Capital Project Grant, New York Percent for the Arts Commission, Art Matters Grant, New York Foundation for the Arts Award in performance art/multidisciplinary work, the Lambent Fellowship in the arts, and the Rema Hort Mann Foundation Award Grant. Biggers' installations, videos, and performances have appeared in venues worldwide including the Tate Britain and Tate Modern, London, the Whitney Museum and Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, as well as institutions in China, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Poland and Russia. His work has been included in exhibitions such as Prospect 1/ New Orleans Biennial, Illuminations at the Tate Modern, Performa 07, the Whitney Biennial and Freestyle at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He has also had solo exhibitions at Grand Arts, Kansas City, Mary Goldman Gallery, Los Angeles, Kenny Schachter's ROVE gallery, London, Triple Candie, New York, D'Amelio Terras Gallery, New York, Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, Matrix/Univ. of Berkeley Museum, Berkeley, Zamek Ujazdowski, Warsaw. Biggers has taught at Virginia Commonwealth University's Sculpture and Expanded Media program and was a visiting scholar at Harvard University's VES and OFA Departments. He teaches at Columbia University.

Major support provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from the Toby D. Lewis Philanthropic Fund of the Jewish Community Federation of Cleveland and the Massachusetts Cultural Council.