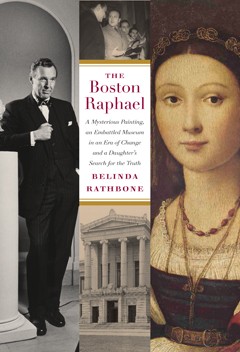

Biographer Belinda Rathbone

Dialogue About Book on Her Father Perry

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 07, 2015

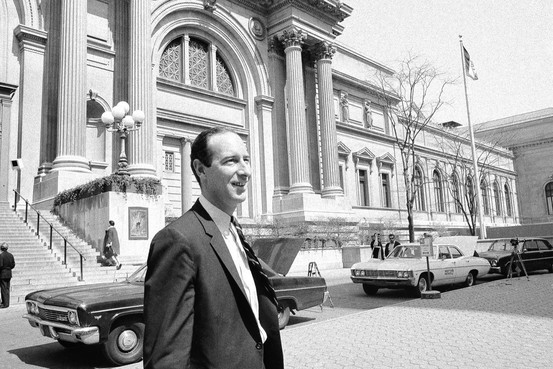

A couple of years ago biographer Belinda Rathbone interviewed me at length in our North Adams loft. It was a part of extensive, multi-valent research for The Boston Raphael a scandal which tarnished the career of her father Perry T. Rathbone. Until the now winding down career of Malcolm Rogers no other director of the Museum of Fine Arts has had a greater impact. He was brought down by a misadventure to acquired a great treasure which has since been downgraded to a heavily restored minor work from the School Of the Italian Renaissance master. Through intrigues and a lack of support from George Seybolt and the board of trustees the painting was returned to Italy where it languishes in storage at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

While the infamous Raphael incident is the focus of the book she reveals a lot about Rathbone and an era which saw great transition and change for major American museums. As they expanded both physical plant and staff, while pursuing ever more expensive and ambitious programming, there was a need for more complex administrative, fund raising and business models. As chair of the board Seybolt insisted on running the MFA as a business which put him on a collision course with Rathbone. As Belinda points out her father had initially been brought to the MFA to initiate changes while respecting the Old Boy approach of traditionally Brahmin trustees.

Recently we again spoke at length about extensive research and issues touched on as background or confined to footnotes. This is part one of that discussion.

Charles Giuliano How has the book been received? Other than my own the only review I have seen has been by Sebastian Smee in The Boston Globe.

Belinda Rathbone There have been quite a few. The review in the Washington Times was positive and quite interesting. There was a review in the Wall Street Journal. That was great. It was very positive but I had a quibble. The reviewer said that I had left something out and I hadn't. All I can say is that people read it as a positive review.

CG How has the book been selling?

BR It's been doing extremely well. We always have to put that in relative terms. It's been doing three times better than Godine (publisher) expected it to do. We're in the third printing. Roughly with each printing they put out another 2,000 books.

CG For a niche publication that seems very good. If you compare that to a major museum catalogue 6,000 copies sold would be very successful.

BR That's right. It was standard that for a photography book, for instance, 5,000 copies was all you could expect.

The New York Times now has a monthly best sellers list by category. Once a month if you go to a category that interests you then you can find the top ten books. The Boston Raphael was among the top ten in the category for Crime and Punishment.

CG (Laughing) You're out there with Whitey Bulger.

BR Yeah. In the company of Orange is the New Black and Sonia Sotomayor. I asked the marketing department at Godine if that means that we can promote it as a New York Times Best Seller? The answer was “of course!” It's going on the jacket of the third printing.

CG Soon to be a major motion picture?

BR That would be interesting. There are a lot of characters. Right?

CG (both laughing) Oh boy.

BR And color and tension.

CG While I understand the focus on the Raphael incident as a means of selling the book this was not the publication I had hoped for. Other than some details I was familiar with that event. There has not been a major study of the MFA since (Walter Muir) Whitehill's book in what, 1970.

BR Right, it was published during the Centennial year.

CG From then to now is an enormous and interesting subject that hasn't been addressed. Those were the aspects of your book that I devoured.

BR The background material, like (my father’s) curatorial adventures. Building projects, renovations.

CG I think we would agree that he was a "Last of the Mohicans" in terms of defining an old school American museum director. During his era the only real comparison is to Thomas Hoving (January 15, 1931 – December 10, 2009, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1967 to 1977). They shared some of the same qualities.

(Hoving held a Ph.D. in the field of medieval art. Rathbone was a generalist who took graduate courses in art history and museum studies with Paul Sachs at Harvard after earning a BA degree there.)

While Perry had a flair for PR and marketing under Hoving the atmosphere was more that of a carnival or three-ring circus. That also has similar problems. For Rathbone there was the Raphael scandal and for Hoving the illegally imported, classical Greek Euphronios krater depicting the death of Sarpedon, which was returned to Italy in 2008.

Hoving evoked protests of racism for the special exhibition Harlem on My Mind. Rathbone's exhibition curated by Edmund Barry Gaither, African American Artists from New York and Boston, avoided those problems.

(Then associated with the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts in Roxbury. Since 1969 Gaither has been director of the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists and adjunct curator for the MFA.)

Hoving appears to have gotten himself into self inflicted problems, while that doesn't describe Rathbone.

BR I think that's right. I loved bringing Hoving into the book and lining them up for comparison. That's always a great thing to do. Hoving was a very flamboyant character indeed. He also represents another generation.

To get back to the point about the kind of book you wanted - the Whitehill book was commissioned by my father for the museum for the centennial. It's a very dry book which is useful. It's about 90% accurate and derived from annual reports. There's no inside story there. It's a report of everything that's gone on and there are some interesting characterizations. They should assign that again, and at some point they probably will.

For the general reader my book is a lot more interesting because it focuses on personalities and takes you behind the scenes. If you get a bit of museum history in there that's cool. People have commented to me that they were so interested to learn what goes on in museums just generally. They had no idea about how they are run and what the problems are. I was glad to bring that to light but also tell a story.

CG It's been a number of years since I read it but I didn't find Whitehill dry. I had such an intensive interest in the subject. For me it was a page turner, particularly because it was so arrogant and autocratic. It told extraordinary stories from a Downton Abbey perspective.

The MFA, for example, had the only Catalan Romanesque apse not in Spain. He tells how it was purchased, removed from the walls taken by mule to a port and shipped to Boston in crates marked Parmesan cheese.

Later when it was discovered missing all of the Romanesque paintings were removed from remote village churches and are now housed in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya which is where we saw them in Barcelona.

Frankly, I think its a more outrageous story than the Raphael.

About relocating the church paintings to keep them away from museums like the MFA, the comment by Whitehill is "That's like closing the barn door after the cows got out."

He also relates how (Edward Sylvester) Morse, (Ernest Francisco) Fenollosa, (William Sturgis Bigelow) acquired a collection of Asiatic art that is among the best in the world.

(They acquired and donated some 4,000 Japanese paintings and more than 30,000 ukiyo-e prints as well as Morse's collection of ceramics and other objects including armor and sculpture.)

Whitehill quotes a letter related to the acquisition of one of Japan's greatest national treasures (the mid-13th-century Heiji monogatari emaki, which chronicles the burning of the SanjÅ Palace). It states the importance of the work and that if the Emperor asked for it the request could not be denied.

(While National Treasures were acquired they were not stolen. Whitehill explains that the Japanese were indifferent and that a number of objects were given or sold cheaply by temples and individuals that owned them. The MFA has strong relationships with Japan including a branch museum in Nagoya. It has been generous in providing access to its holdings but for the Nagoya MFA the Japanese have primarily sought loans of works by French impressionists and post impressionists. The MFA has mounted major exhibitions of Japanese and Asiatic art particularly when its curator, Jan Fontein, became director.)

So there was a history that led to the Raphael incident.

BR There is that history in any museum.

CG Absolutely. Museums were where nations put things that they stole. The more outrageous the theft the greater the museum. Like the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. American museums like the MFA and the Met formed their collections by paying for them (through donations) and not as spoils or war. The great Egyptian collections of the MFA and Met came about through sponsoring archaeology and sharing what was unearthed.

BR We could get into a discussion of the repatriation of those objects. It's a subject worthy of a book. Is that the book you wanted about the MFA?

CG No.

BR You want another Whitehill book just telling you what happened and when.

CG The MFA deserves a book like the wonderful Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970 by Calvin Tomkins. There's nothing like that for the MFA. As you say, Whitehill was a pretty dry guy. He was a trustee and insider.

After Rathbone there is a colorful and complex history with pratfalls and disappointments from the misfiring of Merrill Rueppel who was a disaster replacing him. You touch on that as it related to Rathbone's conflicts with his nemesis, George Seybolt. There was a transition with the colorful classical curator Cornelius Vermeule. Then Fontein as first acting director then director. Bringing in Alan Shestack proved to be a miscalculation. Then Malcolm Rogers was brought in to clean house and launch the museum's greatest period of renovation and expansion.

Today the MFA is a large and vibrant modern museum, which has slowly regained its rightful global status. There is no coherent telling of how it transitioned from the Rathbone years to where it is today.

I think you were too hard on George Seybolt. I'm not talking about his character and personality. He had the right idea that traditional museums needed to evolve into having substantial business models. That's what museums are today. Seybolt was the beginning of that approach. Today the museum's director is primarily a chief curator overseeing special exhibitions and major acquisitions. Museums now have an individual or department in charge of administration and fund raising.

As you pointed out your father was holding down three jobs. He was chief curator. He was the de facto chair of the department of European Painting, which he shared with Hanns Swarzenski (1903-1985 curator of the department of decorative arts and sculpture). Seybolt lured him into being a fund raiser. Prior to that museum directors never organized appeals beyond passing the hat among trustees. He was doing all those jobs.

BR What you describe is a tipping point in the scale of operations that museums were reaching. There was a need to raise money and grow the staff. To grow the plant. Everything. That's where we moved forward. Other museums realized a need for a two- headed administration. That continues today. My father found himself in an awkward situation.

I don't think I'm too hard on Seybolt. People can read the book and believe that he was innovative and an agent of change. Maybe he was seeing things in a way that stodgy old Brahmins couldn't see. That's very clear.

As to his personality I characterized him as others characterized him. I quoted other people, and I quoted him a lot. The most revealing document was his own interview with the Archives of American Art. It's very long and he tells a lot of lies. It's very self serving. He's very insulting to others and I quoted some of these things in the book. I almost didn't want to quote him because it was so mean to these other people. But I did because you have to know just what kind of a person he was. Toward the end of the book I did give him credit for being helpful and instrumental in Washington for policy innovations ,which helped museums. Such as The Indemnity Act which helped with international loans which were too expensive to insure privately. I wanted to give him credit for that. It was his strength. Throwing his weight around in Washington.

But I don't think I was hard on him. I run into people who knew him and they say, yeah, that's the kind of guy he was.

CG If you look at the next MFA administration of former curator then director Jan Fontein he had a close relationship with Howard Johnson (July 2, 1922 – December 12, 2009, president of MIT between 1966 and 1971). From what I understand Fontein had a troubled experience including a break down in a board meeting when he was asked to stay on. In the transition from curator to director he was out of his depth. It appears that he had better support from Johnson than Rathbone enjoyed with the scheming Seybolt.

BR He also had a paid president in Casselman. That was the beginning of the two-headed administrations. Fontein benefited and my father just kind of missed it.

CG Philippe de Montebello reversed course and took back the authority of the MET's director and decision maker.

("It was Philippe de Montebello who set the gold standard for the traditionalists. Over the course of his extraordinarily long, distinguished, thirty-one-year career at the helm of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he has largely resisted the tides of change and run America’s preeminent museum of art in an entirely traditional fashion with unprecedented success.

"Ironically, de Montebello was brought to the Metropolitan not to continue business as usual, but to reverse the museum’s course after the tumultuous upheavals of his predecessor, Thomas Hoving. Hoving had been installed as director with the mandate to shake up the place. Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times recently described his approach to change as that of, “a mad genius who transformed the slumbering Met into a public spectacle: exciting, but lurching from one debacle to another. The modern museum as an insatiable, acquisitive, blockbuster-besotted, mass entertainment palace emerged, with a celebrity impresario as director.” Rayond Liddell, Art New England)

When de Montebello resigned that was indeed the end of the old school museum directors like Rathbone.

BR What about his successor Tom Campbell? (After fourteen years as a curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, specializing in tapestries, he was elected Director and CEO on 9 September 2008.)

CG You tell me.

BR I don't know. Perhaps it's too soon to say.

CG To quote Harry Truman "The buck stops here." You got the impression that all of the Met's decisions both aesthetic, fiscal and administrative crossed de Montebello's desk. You get the impression that he struggled with the board to get back that control after experiencing that you describe as the two headed administration. In fact he discussed that in depth during a lecture at the Clark Art Institute after he left the museum.

BR Even though it was arranged that the salaried president answered to him, still Philippe had a salaried president. That was Emily Rafferty. It was a very good relationship. He was greatly benefited by having Emily take over many of those administrative decisions.

CG I appreciate that you did an enormous amount of research under the constraints of delivering a readable book with a manageable page length.

BR That's why there are so many footnotes. Have you read them?

CG Every one. When studying for degree qualifying exams in graduate school I learned that the most important resources of a book are its bibliography and footnotes. It's how you know what sources the author drew upon and where to go from there as a scholar. So yes, I read your footnotes. Carefully. I wish I had the time to go to the library and look them up.

BR Oh good. (laughing)

CG In the early chapters of the book you described the way the museum was run before Rathbone.

BR Under George Harold Edgell. (1887-1954 he was MFA director from 1935-1954)

CG You described him as a gentleman keeping banking hours and not always in the office. The museum was run as a private club with curators presiding over fiefdoms. Seybolt attempted to change that and tried to get curators to report directly to him. The curators may be in Egypt, Japan or Holland. They are out and about doing the business of the museum with enormous latitude and little or any oversight. My boss, William Stevenson Smith, curator of Egyptian Art was at his desk at ten each day. At four we gathered for tea and sweets served by Sue Thurman. It was a very pleasant lifestyle with modest salaries and benefits. I made $70 a week as an intern.

Seybolt was reacting to that environment by insisting that the museum be run as a business. Perry understood that the departments were fiefdoms and by no means were they equal. Some like Fontein's Asiatic department were rich and powerful. That was true for the Classical Department under Cornelius Vermeule. He had resources to collect coins often using his own money. Clearly he did not live on his salary. While Smith, whose department was not well endowed, had a modest, scholarly lifestyle.

If you fast forward to Malcolm Rogers under the mantra of One Museum, he ended the independence of curators and their departments.

(There was the infamous 1999 Boston Massacre. On a Friday afternoon a number of staff members were summarily fired and escorted from the building. This included two senior curators of decorative arts, Anne Poulet and Jonathan Fairbanks. Poulet was in the midst of organizing an exhibition of work by the French sculptor Houdon. Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. the senior curator of American painting was offered the position of chair of the consolidate Art of the Americas but left to take a position at Harvard's Fogg Art Museum. He is said to be researching a book on modern and contemporary art in Boston.)

BR Are you saying that all of the departments are treated equally under Rogers? I'm asking but I'm really telling that they are not. But I can't go into it because I don't know enough. My sense is that some departments are favored over others. It will always be so. It depends on the director and what needs the most attention now. It depends on the whims of trustees and donors. There are so many factors. They've put a huge injection of energy behind Art of the Americas. All I can say is that other departments feel a little in the shade.

CG You get the sense that, after Edgell, initially Perry was brought in as a young firebrand from St. Louis. He was flamboyant, charismatic, energetic, and had all the right credentials including Harvard and the endorsement of Paul Sachs. He was brought in to make changes, but cautiously. The board was interested in evolution but not revolution. Not to rattle the old boy network.

BR He did these things gently. There were people he found difficult. Any director coming in will find that there are some members of the staff they don't see eye to eye with, and who have some power.

As far as I know he never fired anybody. Except the head of education because he had a serious alcohol problem. It wasn't something he liked doing.

He was eager for W. G. Constable, the curator of paintings, to leave.

CG And never replaced him.

(In 1977 John Walsh was appointed as the Mrs. R. W. Baker curator of paintings. In 1982 after allegedly turning down the position of director of the MFA Walsh joined the Getty where he was director from 1983 to 2000. As I reported in the Patriot Ledger while Walsh worked for the MFA he was a paid consultant to billionaire William I. Koch whose collection was partly on view at the MFA and other museums.)

BR You don't need to fire somebody. You can be patient and work with the system. It's better that way. For one thing you don't give your whole staff a case of the jitters. (As with Rogers when he cleaned house.)

CG As Malcolm did.

BR Yes. We better not talk too much about the MFA today as I would be getting in over my head. I'm not there but I have a sense of it.

CG You've had your ear to the ground. You are the consummate insider.

BR For the era of my father?

CG Yes.

BR One would think. God I lived with the man. What do I know about what he did all day? Not much.

CG What did you talk about at dinner?

BR It's an interesting exercise to work on my own parent. To put him under the microscope as a biographer. You try to put yourself inside their skin and feel what they felt. Suddenly you have a completely different relationship.

As you can see in my book, it was largely research with a pinch of memoir here and there.

I knew names like Maxim Karolik. I probably met Sue Hilles. But to go into the archives and look at the letters and diaries and put the whole thing together. That was exciting.

CG Did your primarily use the MFA library?

BR It was useful for various museum publications. I spent a lot of time in the (MFA) archives and at the Archives of American Art in Washington. That's where my father's papers are. There are also interviews with people who are since deceased. This is how I got a sense of people who were not necessarily on my father's side. It's a side I certainly represent like Nelly (Nelson) Aldrich, a trustee. John Coolidge, another trustee. W.G. Constable. He had an interview there (AAA) and of course, George Seybolt.

All these other voices come into my book. So the research was all over the place. I also have my father's personal correspondence right here in my own basement. So I could locate, for instance, the letter he wrote to my mother from Italy just two days after he had negotiated for the Raphael. You can feel that excitement in his words. They were amazing things to find that you would never look at if he were still here.

CG I was surprised to learn that you were a graduate of the Museum School.

BR I didn't graduate from the Museum School. I went there. Did it say that I had graduated? (laughing)

CG Well, one of my many mistakes.

BR I was there and was there during this tumultuous years actually. So I remember the shows, which were fantastic, like Elements and the Wyeth retrospective.

CG Where then did you go to school and how did the Museum School come into that?

BR I went to Simon's Rock, which is out near you (Berkshires). Great Barrington.

CG Is it a college?

BR Good question. It's a so-called early college which is now part of Bard. It's now called Bard College at Simon's Rock. It's a four-year program from the last two years of high school to the first two years of college. It started as an experiment in 1966. It was started by Elizabeth Hall who was the head of Concord Academy for many years. Should we really talk about Simon's Rock?

CG I'm more interested in how you got to the Museum School.

BR As one of the first graduates of Simon's Rock I came out with two years of college, supposedly, behind me. With a strong interest in photography. That's what I wanted to pursue. So I went to the Museum School for a year. Then I continued to study photography and work on my own. I never got a degree in photography. The museum school was disappointing for me. It was also a tumultuous period for the school. There was very little accountability. It was an art school where students would just come and go. Instructors were there if you really wanted to track them down.

I found it greatly lacking in community spirit. As the director's daughter I was in an odd position there. It was probably the wrong place for me to be. I had a life outside the school and kind of checked in.

CG What did you do with a background in photography?

BR All kinds of things. I continued to work on my photography but it wasn't too long before I realized I wasn't going to try to compete with the great photographers of my own generation as well as the history of the whole medium. I was more interested in working with the medium and with photographers. I was more suited to helping their effort. I started working in the photography collection of the Boston Public Library. I worked in the publicity department at Polaroid.

CG There were a lot of interesting artists working with Polaroid at that time, including Ansel Adams and others.

BR Lucas Samaras and Andy Warhol, Walker Evans. (Evans produced some 2,500 Polaroid photographs.)

CG They had a very active program.

BR Yes, it was an interesting time to be at Polaroid.

CG Did you have anything to do with the Kennedy Gallery?

BR Not really. I organized shows. Traveling shows. Not at the Kennedy Gallery. I organized a big recent Polaroid color photography show which went all over the map.

CG Before we met I read your biography of Walker Evans and loved every word of it. (Walker Evans: a Biography, 2000) He was so interesting and you told his story so well.

BR Thank you.

CG In particular I was fascinated by the discussion of how later in life he had all the negatives under the bed in shoe boxes. He sold them all for a few thousand dollars and thought he had gotten a good deal. Am I wrong?

BR He probably did undersell himself. (1n 1975 Evans sold his entire print collection to a dealer with an option for the later purchase of the negatives.) That was a time when dealers were on the ball. It was a golden moment to buy whole estates. They bought large numbers of photographs from some of the greatest photographers of the 20th century. The market wasn't strong enough at the time for the photographers to charge very much.

So Walker Evans, not being a terribly clever business man, and not having the kind of work which would look like great art for your walls. He was not in a position to charge a great deal. It sounded like a lot of money to him.

CG His connection to Fortune Magazine is fascinating. That he was involved with that exquisite publication coming out during the Great Depression. It's amazing.

BR I know. Fortune Magazine is a kind of disconnect. When you consider that it began in 1929, the same year the stock market crashed. It was the most beautiful, extravagant, elegant magazine of all time.

CG Next to Camera Work. (Published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917.)

BR Ok, next to Camera Work, but that's a different kind of thing. They were the ones who assigned a story to James Agee on Alabama farmers, that ended up in a great book with Walker Evans. (Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941)

Fortune is a great topic. Somebody was going to do a book about it. I was actually involved, but it didn't happen.

CG Wasn't Life Magazine founded around that time?

BR I don't recall the date but Time Life Fortune was the corporation.

(Life was an American magazine that ran weekly from 1883 to 1972, published initially as a humor and general interest magazine. Time founder Henry Luce bought the magazine in 1936, solely so that he could acquire the rights to its name, and shifted it to a role as a weekly news magazine with a strong emphasis on photojournalism. LIFE was published weekly until 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 to 2002.)

CG That was all Luce.

BR Henry Luce.

Interview Part Two.