Joe Thompson Director of Mass MoCA Two

Space is the Place

By: Joe Thompson and Charles Giuliano - Feb 23, 2012

Charles Giuliano During the past 25 years there has been a confluence between personal growth and development and that of the institution you brought to life and nurtured through stages of growth and progress. Can we discuss that private and institutional process? It is remarkable that your entire professional career has been devoted to what is now among the foremost institutions for contemporary art. Are you more mature now?

Joe Thompson Let’s hope so. You do change over time. You only take on projects like this when you’re very young. For one thing you know too much as you get older. You know how long and difficult it is.

CG How tough and scary was it?

JT You know when you’re young it always seemed like something we could do that was just six months away. If we could just hammer away for the next six months and raise the next $500,000. Complete the next XYZ or get the next person on board. Move a politician from here to there. There always seemed like something concrete that we could do that was three or four or five months of work. That could be achieved that could make the project work. That was utterly naïve in retrospect. (Laughs) It took fifty of those kinds of moments. But when you're in your mid to late twenties and early thirties…

CG Today your salary is normal and comfortable but during the twelve years of development you must have been living on vapors.

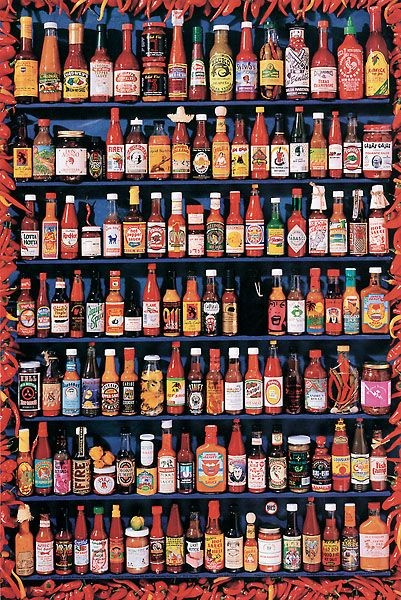

JT We made and sold hot sauce.

CG (Laughs) What do you mean you sold hot sauce?

JT Yeah we sold hot sauce. That’s how we made our money. That’s how we lived.

CG Who is we?

JT Jennifer and I. There was no money. So we had to make money somehow. Jennifer had written a book about cooking with hot sauces. We decided to have our own label and brand. We quickly moved from cooking it at home to having it cooked. We designed posters. First hot sauce but then other posters. We did one on micro brewery beers. Scotch. Different kinds of fruits and vegetables. You’ll see them out there.

CG The poster of a grid of all those different hot sauces! That’s yours?

JT Yeah. Together Jen and I made what, ten or fifteen posters.

CG And that paid the bills.

JT In part. It’s like a hundred different streams. You get consulting jobs here and there.

CG The perception is that you are one of those privileged Williams trust fund kids.

JT No. That’s not true. We had to work. We both worked really hard to hold it together.

CG Were you scared?

JT How scared are you when you’re 27? Really. No family. No kids. It was incredibly fun. It was difficult and frustrating. There are many times, had there been a graceful way out, we would have taken it.

CG Given all the challenges and difficulties how then does it feel to be sitting here today having established a great museum?

JT It feels two thirds done. I want to get back to your very interesting earlier question. Which related to the art and the balance between long term installations and changing exhibitions.

CG As a part of that can we discuss your plans for a long term Anselm Kiefer installation (similar to LeWitt) despite your many denials.

JT Absolutely we will. The LeWitt project and the grounding in recent art history just changed the feeling of what it means to be here in this three ring circus of changing exhibitions. It makes a difference for visitors when they come here. And to get to your question of how one changes a view of what an institution is. I’ve come to think that my own personal nirvana, with respect to buildings, is neither Mass MoCA One, which is the Dia Beacon model, a fixed depot. Nor is it Mass MoCA Two which is a Kunsthalle with a great performing arts program attached on the side. Fundamentally as a Kunsthalle you are as good as the last show you did.

We turn out exhibitions. You write about them all the time. Sometimes you love them sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you can’t understand what we were thinking when we did them. It’s a cycle of ups and downs and we are as good as what’s on display that moment. That’s a tenuous existence in my view for a museum.

My view of nirvana is one that has the best of both those worlds. A vibrant changing exhibition program that drives people and gives them an excuse to come to the Berkshires in the summer because they have to see what’s in the big gallery at Mass MoCA. When they get here there is a reassuring presence of Sol LeWitt. Soon, Anselm Kiefer. The question then is can we do that three or four more times? What’s the right balance? What if we had 150,000 square feet of great moments in the history of recent art? And our current 150,000 square feet of changing exhibitions. Three or four big changing exhibitions each year. That’s a beautiful place to come to. Overlaid with a performing arts program that does 60 to 70 events a year. That’s my idea of a really interesting museum.

CG I never thought I would say this. There may come a time when Mass MoCA runs out of developable real estate.

JT Huh. (exclamation) You know. It’s crossed our minds. It’s a very good point. The board of trustees has a habit of leading me through five year planning and thinking exercises. It’s one of the great things about boards because they force you to be thinking five and ten years down the road.

For the very first time in our cycle we thought forward to a world where we could be running out of space. It changes how you think. You move into an allocation mode. It becomes more precious and less free wheeling.

I’m a great believer in being an opportunist. Particularly getting started with a project like this where you have a lot of space and time. You have a strong feeling that you would make a bigger mistake by trying not to make mistakes. It’s important to keep batting and keep taking big risks. As you start to run out of space you begin to think slightly differently. About what you’re willing to do and the time frame around them. Up until the past three years I was willing to take on outrageous projects and put them up for a very very long time. Suddenly you find yourself thinking hard about delimiting the time a little bit. Limiting the space a little bit. It’s a different way of thinking.

CG You talk about the board and those five year increments. I’ve been covering Mass MoCA for 25 years and not always on the best relationship. Unlike the board I’m an outsider with a different set of sources. The LeWitt building was indeed a game changer. When you undertook the project there was a learning curve and risk factor. Now that it is an unqualified success that would seem to open up the potential for working with other artists, like LeWitt and now Kiefer, as well as attracting interest from the many major private collections. It returns to the Krens premise of leveraging the fact that such a large portion of museum and private collections languish in storage.

JT For a reason usually. They’re in the basement for a good reason.

CG I’ve heard for instance that what is stored at the Menil collection (Houston) is not up to what is displayed in the museum. It somewhat debunks the notion of a ‘great eye.’ It would seem today that there are a number of major collectors who would be more than willing to strike a deal for significant space at Mass MoCA. Arguably there are more players than space for their collections.

JT A couple of things are true. The past twenty five years has seen the formation of more great collections than in the entire 200 plus years of our country. It was a gilded age. Coming to a halt in 2007. That part of your statement is absolutely true. There are numerous, distinguished, very deep collections out there.

CG Do you know them and do these questions come up?

JT I know them. One of the things that interests me about the LeWitt model, in partnering with institutions like Yale, and Williams, Mass MoCA and its public reap many of the benefits of having a core collection. With none of the liabilities.

Once a museum begins to collect it changes your DNA. Suddenly you find yourself festooned with conservators and registrars, insurance requirements and administrative overhead. That acts purposefully to slow an institution down. It becomes about protection and preservation. It’s about taking care of history. Taking something of value and taking it forward in time and delivering it to the future in the same condition that it is now.

It’s a completely different way of thinking than we think at Mass MoCA. Which is open platform. We create space and time for artists to make new work. Show it. Then move on to the next new work. Those two models are not antithetical but they are different ways of approaching a museum. If you are focused on preserving and protecting you don’t have a lot of people on staff like Richard Criddle and Dante Birch who are helping artists making things. It is just a different way of working.

The question then arises of can you have both? I think the LeWitt points a way. We don’t own that work. We have great partners. In this case Yale and Williams College. So we have the scholarly apparatus and the archival expertise. To take care of the work. Which is not our role here. We have the space and the time.

In that sense your question and instinct is well founded. As far as can we find the right kinds of partners with the right kinds of art. Mass MoCA is never going to be, in my opinion, a museum which shows great easel paintings on canvas. There are so many places which can show it so much better than we can.

CG Along those lines today you would never be able to do the Rauschenberg installation which inaugurated the space in Building 5.

(May 1999 to April 2000… “The 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece was a monumental work-in-progress that Rauschenberg began nearly two decades ago and continues to work on intermittently between other projects. Although the number of pieces shown and the exact sequence may vary from one installation of the work to the next, in its entirety the work currently consists of 195 parts and measures nearly 1,000 feet long; when completed, it is intended to reach the entire length of its title and perhaps beyond. By its sheer size and through both visual and aural elements, this multi-part work creates an encompassing environment.”)

The artist is now deceased. The work would be a part of the estate or some collection or collections. Anyone loaning the work, other than the living artist, would put demands for climate control, light levels, and conservation. Building 5 meets none of those requirements. Also the insurance value of the work would be prohibitive.

Today there is no way that you could do that project.

JT That goes to the point of picking the right partners. Bob’s own team put that question to him. The place was not climate controlled. He had a very large studio staff. One of them who served as registrar, we were just getting ready to install it, the crates were already there, turned to him and said “Bob this is not archival.” Obviously we had told him that before. The reality of it dawned on them when they saw the big windows and the fans. Bob just turned to them and said “So, will you tell me some other place where I can show this work?” (laughs)

CG I can just see him saying that.

JT And of course there is no answer. He said “Ok then let’s mount it.” And that was it.

So a collector who has an immaculate collection of Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein and Warhol that wouldn’t be our cup of tea. Could we convert these buildings into perfect climate controlled galleries? Of course you can. But you’re spending more than it would cost to build it from scratch. Because you are having to build a building inside a building. You have to deal with the columns and vapor barriers. Where these are incredibly economic spaces if you use them for what they are.