Beckett's Elusive Endgame at American Repertory Theatre

Stunning Play Features a Brilliant Cast

By: Mark Favermann - Feb 25, 2009

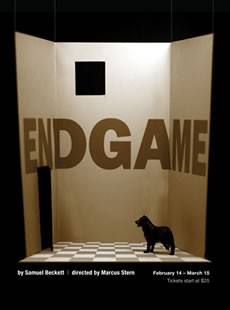

EndgameBy Samuel Beckett

Directed By Marcus Stern

Set design by Andromache Chalfant

Costume design by Clint Ramos

Lighting design by Scott Zielinski

Cast:

Hamm, Will LeBow

Clov, Thomas Derrah

Nagg, Remo Airaldi

Nell, Karen MacDonald

At the Loeb Drama Center

The American Repertory Theatre

Cambridge, MA

Feb. 14 to Mar. 15

Running Time 75 Minutes

The American Repertory Theatre is one of those theatrical companies that is expected to present an original or edgy interpretation of a play. During his lifetime, and through his estate, the works of Samuel Beckett are mandated to be presented exactly the way that the playwright scripted it with every pause, breath, and sound in an exactly pronounced rhythm. Beckett has even prescribed the sets in minimalist terms. So, unlike most of its other shows, the current production of the American Repertory Theatre is highly prescribed. In a post modern sense, it is a Theatre of the Absurd classic. It is also one the most completely brilliant set of performances and production values seen in the last several seasons at the ART. The show is simply stunning.

Endgame was written after playwright Beckett had lost all of the members of his immediate family. The narrative, such as it is, deals with four characters wrestling with death and despair. The play is set in a large, spare, open space dilapidated room with two mostly boarded-up windows that can be seen out of near the top. Supposedly, on the left side window, there is only a view out to sea; out of the right window, is a view of the earth. A door on the right side of the room presumably is the entrance to a kitchen. Two trash can lids are affixed to the floor. As always, the set design at ART is itself a work of art.

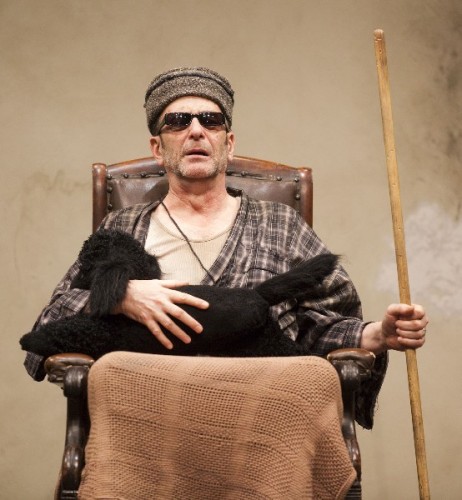

Seated in a lounge chair that is set on a platform with castors is Hamm (played by Will LeBow) who is both blind and wheelchair-bound. He is the master of the estate. His servant and/or perhaps son is Clov (Thomas Derrah). Peaking out of the trash cans are Hamm's parents, Nagg (Remo Airaldi) and Nell (Karen MacDonald). The wordplay, its ambiguity and innuendo come fast and furious. Hamm is profoundly despairing while Clov is reactively overwhelmed. Clov is the only character who is ambulatory. He alone can see out of the windows. Is he viewing the future? He has to climb a ladder each time to look with a spyglass. He serves Hamm but not without a strong verbal or visual reaction each time. This appears to be the child reacting to a parent, perhaps just the child in rebellion, or the servant fed-up with an abusive master. It could be all of these.

Initially, Clov is rather spastic in his movements. He is continually moving. His conversation with Hamm is a bit like a couple of vaudevillians, one a straight man, and the other a jokester. Laughter in Beckett's plays is a bit guilty on the outside and often just internalized. There is an Abott and Costello (Who's On First?) quality to many of their exchanges. The rhythm of the words, the inflection of voices, the pauses, create the patter of the play. LeBow and Derrah seem to have almost perfect pitch pinging words and phrases back and forth like fast tennis shots. From their conversation, we learn that there is a flood engulfing the estate. Beckett may be suggesting here that this is the Great Flood (Hamm is a son of Noah), the watering down or washing out of life.

Hamm's interaction with Nagg and Nell, his dying father and mother, is rather negative. The parents are relegated to living in trash cans and have apparently lost their legs. Symbolically, this is the rejection of parents, reassignment of the vital human being to the refuse can of society, or just a strange image of undetermined negativity. The parents have literally lost their footing, their way, and their son Hamm is their reluctant and angry caretaker, their not so benevolent benefactor. Nagg is first seen asking for his "pap,"a type of porridge. Elderly people are often focused upon food. Clov says that there is no pap left. Clov continues to report running out of supplies throughout the play. This may be time running out. Eventually, Clov runs out as well.

Each of ART's ensemble actors is fabulous here. Clov is brilliantly portrayed by Thomas Derrah. His stagecraft and movements are dance steps to the unclear words and images. LeBow's Hamm is masterful seated the entire time in one position. Playing a blind man, apparently, LeBow does the character with his eyes closed. LeBow's performance is wonderful.

Visually, Remo Airaldi and Karen MacDonald are startling when first seen. Remo Airaldi's Nagg seems to channel a feral creature and a bit of an elderly, toothless Cowardly Lion. MacDonald has the look of a wizened hag, a benevolent witch, or earnest bag lady. Using only their head, shoulders, and hands to portray their parts, Airaldi and MacDonald's comparatively minimal dialogue is on a par with the eloquence of that of the Derrah and LeBow characters. Bravo to all the actors. This is ensemble acting at its finest.

Karen MacDonald's Nell sums up much of Endgame and Beckett's dark themes in her short speech. "Nothing is funnier than unhappiness. I grant you that...yes, yes, it's the most comical thing in the world. And we laugh, we laugh with a will, in the beginning. But it is always the same thing. Yes, it's like the funny story we have heard too often. We still find it funny, but we don't laugh anymore."

After World War II, the Irish playwright, novelist and poet, Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) focused his creative work in a subjective way that was drawn from his own personal inner world. Four major plays, Waiting for Godot (1949), Endgame (1957), Krapp's Last Tape (1958) and Happy Days (1960) all demonstrate the will to survive in the face of abject despair set in an incomprehensible and unyielding world.

In all of these works, black humor is the dark shade of the dialogue. Some writers and critics have categorized Beckett as an existentialist, though Beckett himself rejected this notion. His plays have been referred to as Theatre of the Absurd, considered existential, and likened to the works of a true existentialist Albert Camus. This allows for much academic debate.

The brilliance of Endgame and much of Beckett's other work is found in the ambiguity and layered meanings of his words as spoken as well as what is not, the designated silences and pauses. There is so much to ponder here. Who are these characters? Are they parts of the same person? Is Clov the son, the servant or the mirror reflection of Hamm? What did the parents do to Hamm? Is man always flawed? Here, the entertainment is in our personal acknowledgment of our shared humanity, our misunderstanding of it, and our attempts to clarify what is unclear. This play is a microcosm of the absurdity of society, but it is also an eloquent tonal poem about our human condition.