Sensorium at MIT List Visual Arts Center

Exhibiting the Five Senses

By: Charles Giuliano - Mar 06, 2007

Sensorium: Embodied experience, technology and contemporary art

The MIT List Visual Arts Center

Curated by Bill Arning, Jane Farver, Yuko Hasegawa, Marjory Jacobson and Caroline A. Jones. The artists include: Mathieu Briand, Janet Cardiff and George Burns Miller, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Ryoji Ikeda, Christian Jankowski, Bruce Nauman, Francois Roche and R&Sie(n), Anri Sala and Sissel Tolaas. Catalogue edited with an essay by Caroline A. Jones with entries by the curators and a Abecedarius (from "Air" to "Zoon') by Caroline Bassett, Michael Bull, Zeynep Celik, Constance Claussen, Johnathan Crary, Chris Csikszentmihalyi, Mark Doty, Joseph Dumit, Michel Foucault, Peter Galison, Donna Haraway, Martin Jay, Amelia Jones, Hiroko Kikuchi, Stephen M. Kosslyn, Bruno Latour, Thomas Y. Levin, Peter Lunenfeld, William J. Mitchell, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara Maria Stafford, Neal Stephenson, Michael Swanwick/ William Gibson, Sherry Turkle, and Stephen Wilson. The MIT Press, 260 Pages.

In light of this provocative exhibition and its dense theoretical accompanying catalogue "Sensorium: Embodied experience, technology, and contemporary art" its host the MIT List Visual Arts Center, in line with its own research and development, may well be mandated to change its name to the MIT List Center for the Five Senses. The thesis of this intellectually challenging and provocative project is that in the context of exhibitions and all matters related to the fine arts that sight, the dominant sense, must now make room for taste, touch, smell and sound.

There is a sub theme that conflates with the popular television program Fear Factor as several of the artists of this massive undertaking, that took a season to present in two parts, confront us and ask us to overcome phobias by drinking tea distilled from our urine, experience the smell of fear applied to the gallery walls, wear head gear that approximates the experience of schizophrenia, or through night light video overcome our fear of the dark.

It is entirely appropriate that MIT as a world renowned center for research in science and technology should take on such a daunting project that literally challenges and redefines our basic notions of the "visual arts" and what is appropriate to present and discuss in the context of an exhibition. But the very nature of such an undertaking has factored into it a degree of difficulty that is off the map of the usual audience for exhibitions and may be legible to a handful of global experimenters on the cutting edge of defining the limits and definitions of art. This implies a risk factor and willingness to accept failure. That the works themselves may fall flat as an exhibition experience or that the dialogue they induce fails to communicate. Or the works are so esoteric and specialized that they are beyond the scope of even the most sophisticated and ardent viewers and readers.

But much to the credit of the List as a globally respected museum under its director, Jane Farver, it is a risk and challenge they take on with verve and even a smidgen of perverse and ironic humor. Now that we are contemplating moving out of Boston to the Berkshires the List is precisely what we will most miss in the bucolic mix of Western Massachusetts museums even though Mass MoCA lumbers along with its mostly awkward notion of the avant-garde. For the genuine article there is truly nothing to compare with the exhibitions and projects mounted by Farver and her associates at MIT. In these past few years the List has put my poor head through the wringer and I feel much the better, thank you very much, for the experience.

But taking on the challenge of Sensorium needn't have been as difficult as it proved to be. The primary essayist and editor, Caroline A. Jones, is positively brilliant. But she is a tough read and assumes that we are on a level playing field with her range of knowledge of science, technology, philosophy and esoteric observations on everything from popular culture to recreational prosthetics and pharmacology. Having read her 44 page essay with five pages of notes rather slowly and carefully I may claim to understand the drift and bits and pieces. While originality and insight are her long suit, communication and compassion for the reader, are shortcomings. If we are to be won over to the important concepts embedded here we need more access to her critical thinking. Otherwise, one has to read with a dictionary and patiently Google every reference. Most of all it seems imperative that a pioneer who wants to change critical thinking in the field is obligated to make us feel that it is worth the effort by inviting readers into the text. And no, this does not imply dumbing it down. Perhaps it means better writing and editing. While Jones was the editor of the catalogue the question is who was editing Jones? And the book design further exacerbated the situation by printing the text in ten point, sans serif, in blue pencil blue. It is a color intended to be invisible to the camera when you make corrections to proofs but in this case it also is somewhat invisible to the reader as well. Oddly, the notes that follow the passages of text are printed in black. At the very least, the "designer" might have reversed the order and had one struggle to read the notes rather than the main body of text. Do I quibble? Perhaps, when one considers that, arguably, this two part exhibition and accompanying text may prove to be the most important, innovative, and influential exhibition staged anywhere in the world this season. I am willing to wager on that and only time will tell.

Not that there is that much to see in these two installations. But Jones does a right fine job of beating up on the dominance of the sense of sight. Her punching bag in this the best crafted and most accessible part of her thesis is that oh so large and cushy target, Clement Greenberg. Many of the arguments have been pulled out of her book "Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg's Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses." She absolutely savages him for blundering in an early essay on Mondrian's "New York (sic) Boogie Woogie" when he wrote that he saw orange and purple in the painting. A huge gaff because, of course, the artist used only primary and not secondary colors. That was the point of Mondrian and Jones is brutal and merciless in not allowing him that mistake. She also attacks his description of the "threadness" of the texture of the unprimed canvas ground of the Morris Louis drip paintings. Of course we all know what Clem meant by terms like "flatness" and "threadness" and his quaint lexicon of terms but Caroline is of a different and more disciplined, post modern generation and will have none of his Kantian sloppiness. Poor Clem. Surely, this is the most accessible aspect of her essay and it is most familiar as people of my age in this field grew up on Greenberg and know him inside out. What is more slippery is her statement that half of the brain is used to process sight and that a good chunk of the people of Great Britain are on Prozac. It is interesting that smell has the weakest vocabulary to describe its sensations. And what are the implications, as Jones discusses, of products that render us odorless in a smelly environment? Or how, she asks, did we progress to colorless, clear liquids that deliver the "taste" of exotic fruit with no calories for the consumer? There is much to think about in her text as we struggle to keep up with her fast pace over uneven and unfamiliar terrain.

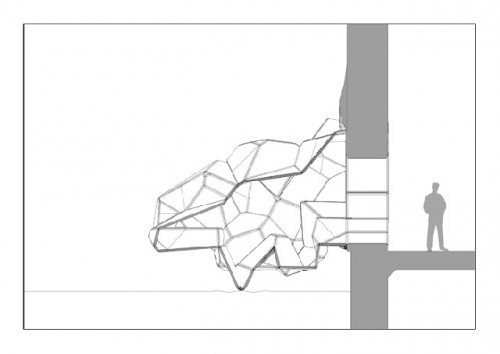

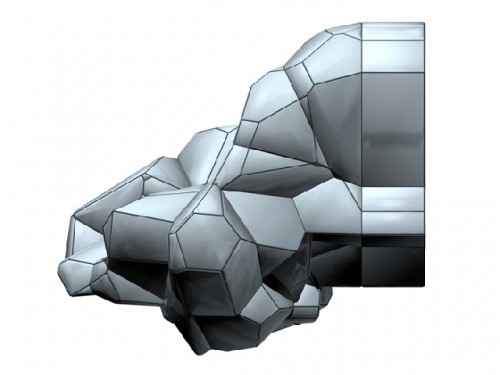

In addition to viewing both installations Astrid and I also attended the two and a half hour panel discussion moderated by Jones. It was a formidable performance and, again, I can testify to grasping only an increment of the presentation. The discussion of "architecture" by Francois Roche, a Parisian, was fascinating but difficult to follow as he speaks English with a thick accent. He talked at great length about overcoming fear and phobias. Of making structures in Venice the walls of which sucked up the polluted water of the lagoons. Or buildings in polluted cities made from dust and soot. Farver informed the audience that it was only at the last minute they learned that his project for an MITea house involved distilling urine into tea. It appears that it is an accepted religious and alternative medical practice. They had thought it was about purifying waste water from the labs. Not piss.

Because of the range of works and the need to present the artists with adequate space it was decided to split the exhibition into two parts. Some of the more interesting works were displayed in the first segment. In particular the "smell art" of Sissel Tolaas. Farver informed the audience, with some irony, that none of the other artists wanted to display their work next to hers. Ah the potency of odor particularly of an unpleasant nature evoking the scent of "fear." It is difficult for us to perceive but we are all too familiar with how an angry and threatening animal can sense or smell our fear. This exhibition all too well demonstrates the limits of the range of human senses compared to those of the animal kingdom. The work by Cardiff and Miller was also compelling particularly when compared to most of the other installations. For Sensorium they created a diorama that we look into. It is the room of an unidentified opera buff. They found a stash of records with the name of the owner whom they opted not to identify or encounter. Instead, they created an environment and persona for the missing person and his obsession with sound, specifically opera, in the remote wilds of rural Canada. In the "walks" of Cardiff, and her collaborations with Miller, they have exhamined the possibilities of sound in the realm of sight. Bruce Nauman explored the terrors of night by setting up a night vision camera, resulting in an eerie green video, to record the "events" in his empty studio. If you wait long enough you get to see a bug fly by which is a really huge incident.

The head sets of Mathieu Briand, which simulate the disoriented vision of one suffering from schizophrenia, mostly didn't work. On the night of the panel there were a number of people in the gallery attempting to try on the equipment and getting fairly rough treatment from the "guards" in the gallery who showed little or no patience. It was surprising that these were the same observations of the students I assigned to view and write about the Sensorium show. Overall, the students had a tough time with the exhibition and getting roughed up by attendants who are supposed to help visitors was very off putting.

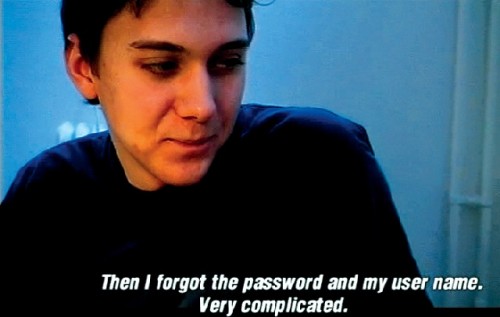

The students also complained about the "ugliness" of the amateur actors in the Christian Jankowski video. It recalled an earlier time when he and a girl friend separated by great distance, and having no money, agreed to meet in internet chat rooms. He transcribed the conversations and hired kids to reenact the dialogues. The level of "acting" was terrible but the concept was absorbing and overall the video was provocative although it is difficult to stipulate just which "sense" was being evoked by the piece.

Some two hours into the panel discussion, Jones threw it open to questions from the audience. Many of the statements/ questions were remarkable. The kind of dialogue one only expects in Cambridge at an MIT lecture. Several times I had suggested to Astrid that we leave and have dinner, as we did eventually, at Legal Seafoods. Having worked for many years for the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT she didn't want to leave. Over dinner she discussed how vitalizing it had been to recall all the years of attending just such occasions. But I was intrigued by the seemingly agressive question of Ken Johnson of the Globe when he asked just how MIT and its program in arts and critical studies might prepare students to do the kind of work, if, indeed this is the future, as was displayed in Sensorium? The Jones response was really terrific when she stated simply that "we just push them out the door." Indeed.

It will be interesting next year when, as a member of AICA New England, the organization of art critics, to see whether Sensorium will be nominated for recognition. I believe part one qualified for consideration this past year but was passed over. The List has another shot at Sensorium 2. For me, it was the most challenging and provocative exhibition I have seen since the Dieter Roth retrospective at MoMA/ Queens a couple of years back. These are the kind of projects that really get inside and change you. They invade your mind and guts. But just how many folks are up for that kind of rough tossing about? Is the art world ready for "smell art," or art that stinks, and "taste art" that involves piss tea and, well, you get my drift. Fittingly one of the entries in the Abecedarius is the "yuck factor." My goodness.