Letter from Southern California

Exhibitions: Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980

By: Patricia Hills - Mar 19, 2012

A trickle of news from sunny California alerted me last fall that a huge undertaking was taking place in Southern California. The Getty Museum had not only organized a major exhibition, “Pacific Standard Time: Los Angeles Art, 1945-1980,” scheduled to be on view from October 1, 2011 to February 5, 2012, but had also given out some $10 million in grants to other Southern California museums to mount their own shows.

All together more than 60 exhibitions took place, with the majority of them on view between October and mid-February 2012. Only a handful would be still around when the College Art Association annual conference met in Los Angeles the third week of February (poor timing).

I had to go there before February. I could then see some of the exhibitions, while also catching up with some of my California children (ex-pats from Cold New England) and soaking up some sun. This would take some planning, especially as I juggled my own itinerary, the geography of Southern California, and the closing dates as well as the open hours of the museums—some closed on Mondays, some on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, etc.

Off I went right after the New Year rang in to see what I had been missing by living in New York and Boston during those years.

Day 1--Thursday, January 5, 2012: My son Brad, who lives in Santa Monica, picked me up at LAX and drove me first to the Otis College of Art and Design (founded in 1918 by Harrison Grey Otis, of the Boston family, who made a fortune in LA by being the publisher of the LA Times). The exhibition, “Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building” was held at the College in a very large exhibition space divided by baffles at angles going this way and that.

The focus was on the history, the activities, and the participants of the Woman’s Building inLos Angeles. Not exactly Art, but artistic—a sprawling archive filling up table cases and stretching up the walls to the ceiling. The archive was created by L.A. artist Bea Lowe, an early participant determined to archive “a compiliation of every public event that had ever taken place at the Woman’s Building,” according to the exhibition’s website. She passed these materials along to Terry Wolverton who worked with Sondra Hale and others; art historian Michelle Moravec provided a timeline.

The exhibition thus consisted of large blow-up photographs of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro (well known on the East Coast) and other West Coast artists; photos of “Womanhouse,” the 1971 temporary collaborative installation put together by Schapiro’s and Chicago’s students in the Cal/Arts Feminist Art Program, snapshots, Suzanne Lacy’s performance projects; correspondence, flyers, newsletters, along with the huge time-line. A lot to absorb, but that’s why catalogues are useful.

Doin’ It in Public characterizes the growing practice among artists and museum curators to create the “archive exhibition.” Hence, “the work of art,” becomes a collection of photographs, letters, leaflets, programs, government documents, ephemera, sometimes artifacts (souvenirs, studio props), often enhanced by video monitors and audio tapes, and carefully organized within a curated space. Like the Humongous Fungus, which mainly grows underground in the forests of Michigan and Oregon and can cover 37 acres or more and seasonally sprouts genuine poisonous mushrooms [see Tom Volk’s website about Armillaria gallica], we need to think of the archive exhibition as one unit, a 21st-century Gesamtkunstwerk.

If Art is communication, the archive exhibition is certainly that. For it does elicit in the viewer some of the same responses as traditional Art: it persuades us to meditate on our memories of history, of our origins, and of the process of coming to new consciousnesses. To extend the mushroom metaphor, the ephemera in such exhibitions as Doin’ It in Public are the nutrients that keep the narrative of life struggles alive. As a product of feminist consciousness-raising groups in the early 1970s, I respond to this stuff. It—and I speak of “it” as a unitary thing—has a palpable reality that touches me. Does it appeal to the eye? Depends on one’s taste.

We can have the coolly Apollonian, constructed installations by Christian Boltanski about Holocaust victims or the messily exuberant Dionysian exhibitions, such as “Hungry for Death: Destroy All Monsters,” installed by Kate McNamara for the Boston University Art Gallery in the fall of 2011. That archive exhibition brought in ephemera drawn from the archive of Destroy All Monsters, the punk/rock/heavy metal Detroit group of the early 1970s. In both cases, the style of the installation matched the affective content of the subject: noisy, boisterous, performative. (Complete disclosure: I was on the BU search committee that brought Kate to the BU Art Gallery.)

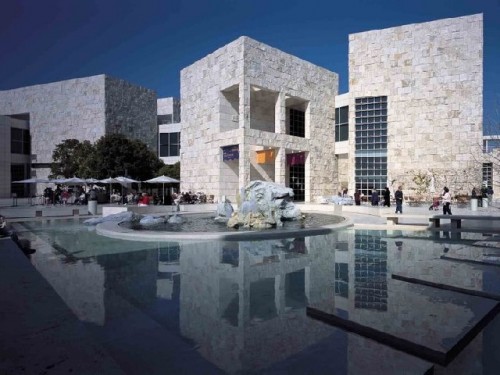

But Day #1 is not over. We then drove on to the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center—that elegant collection of luminous architectural forms you can see from the San Diego Freeway (405)—high in the hills of the Santa Monica Mountains overlooking the Pacific Ocean. We parked in the Getty’s lot half-way up the hill, and I took the tram (Brad ran up for the exercise) to the plaza, the central space of Richard Meier’s Getty Center. It was like stepping through Bernini’s Arcade into the Piazza in front of St. Peter’s in Rome. What a fabulous set of interpenetrating forms and spaces!

Meier had selected 1.2 million square feet of “beige-colored, cleft-cut, textured, fossilized travertine” from Bagni di Tivoli, Italy, for the exterior of the buildings (see the Getty Website). Hence, the Art that really overwhelmed was that ensemble of perfectly placed plaza, buildings, terraces, external staircases, gardens, the clear blue sky, and the splendid view of the Pacific at sunset.

But, oh yes, we were there to see the lead exhibition, Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970, and the three other related Getty Center exhibitions that participated in the PST initiative. Leisurely finishing our lemonades in the 70-degree, breeze-caressed plaza, we ducked indoors to see the Getty’s chronologically organized lead exhibition, Crosscurrents. Because the installation began with a focus on painting and sculpture of the post 1945 years, it served as a good introduction to all of the PST exhibitions in Southern California.

The mid-century abstract paintings of Lorser Feitelson, Helen Lundeberg, and John McLoughlin and the large ceramics of Peter Voulkos, Henry Takemoto, and Ken Price dominated the first rooms, but we quickly moved into the funky 1960s with collages and assemblages by Edward Kienholz, George Herms, Wallace Berman, Melvin Edwards, Ed Moses, and Betye Saar. We would see a lot of these last six artists before concluding the California trip. Back East we have always known about Kienholz, Edwards, and Saar, but Herms, Moses, and Berman have had less East Coast exposure.

Leaving behind the messy collages and assemblages, we moved on to see pictures of pretty young men and outdoor swimming pools by David Hockney and waves by Veja Clemens. Llyn Foulkes and Joe Goode seemed to be the California response to East Coast Pop Art. With Billy Al Bengston and Ed Ruscha, both of whom are somewhat Pop, we became aware we were entering rooms of paintings with smooth surfaces. Wall labels began to introduce the term “finish fetish.”

This is an especially apt term for the early 1970s paintings and sculptural works of Judy Chicago, who, like other artists, was inspired by the custom car spray-painting popular in the ‘hoods of L.A. These galleries gave way to “Perception and Process” with artists such as Mary Corse, a painter who drew inspiration from “Light and Space” artists Robert Irwin and James Turrell. Corse’s Untitled (White Light Grid Series-V of 1969 shimmered with its surface of “glass microspheres in acrylic on canvas.”

By this time my mind bubbled with phrases that blended, blurred and slurred—finish fetish, light and space, perception and process, process painting—all terms that erased the idea of readable subject matter, to be replaced by an intense experiential apprehension of surface. Switching gears on the aesthetic was relevant to the sculptures of Chicago, Fred Eversley, Craig Kauffman, John McCracken, and De Vain Valentine.

Wall labels also had a pedagogical function, to remind us of the roles played by a network of dealers, critics, and curators, who promoted California art, such as Walter Hopps and Irving Blum of the Ferus Gallery; Virginia Dwan of the Dwan Gallery; Lawrence Alloway, who flew into LA as a guest curator; and John Coplans and Philip Leider, who moved the new magazine Art Forum from San Francisco to Los Angeles where the art scene was popping.

Anyway, stepping out of the exhibition and back onto the balcony to catch the waning sun shimmering over the surface of a quiet ocean, we headed back to the tram and drove on to the UCLA area to visit the Hammer Museum on Wilshire Boulevard to see the PST exhibition Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980. The museum was crowded at 7 pm that evening, since the exhibition was closing in a couple of days.

The Hammer’s show was the reason I flew to Los Angeles in early January, and it did not disappoint. Here were many works by familiar artists—Charles White, Samella Lewis, David Hammons, Fred Eversley, Mel Edwards, and Betye Saar—as well as artists whom I, and I suspect many other East Coast art types like myself, had never heard of, such as Willaim Pajaud, Senga Nengudi, Noah Punifoy, Alonzo Davis, John Outterbridge, Daniel LaRue Johnson, and John T. Riddle, Jr.

Assemblage dominated the exhibition, perhaps because, as the catalogue stated: “Assemblage became a key artistic strategy of reclaiming discarded objects and transforming them into expressions of collective social experience.”

Hammons, Edwards, and Saar were shown in depth, as were Outterbridge’s powerful sculptural reliefs and stuffed fabric human forms. Johnson’s black wooden boxes with the faces of black-painted dolls peeping out through holes were compellingly political, as was Purifoy’s 24 x 24 x 6 inch lump of charred remains of who-knows-what, titled Watts Uprising Remains. Riddle’s constructivist scrap-metal sculptures consist of an amalgam of shaped metal with recognizable elements of human forms welded together with abstract fragments. Gradual Troop Withdrawal of 1970 includes one sculpted trousered leg and shoe linked to a skeletal hand; the “figure” swoops backwards, off-balance, vulnerable, and damaged—a strong metaphor for psychologically impaired, returning soldiers.

The works in the show that I found particularly repellent were the constructions of Senga Nengudi—pantyhose poked with large holes, twisted and stretched across the wall while simultaneously nailed to the floor. I cannot conceive they were meant to be anything but strangely horrific—tapping into visceral feelings (of creepiness or yuckiness). Were they reminders of the murder-weapon-of-choice of stalkers, Hillside stranglers, et. al.—men obsessed with wreaking horrible torture on women with women’s own clothing? Or maybe just a reminder of the mildly irritating, physical ordeal of getting both feet and legs into “control-top” pantyhose without getting snags, runs, and holes?

When I turned my back on Nengudi’s works, I confronted a buoyant construction by David Hammons called Flight Fantasy, 1983, made of broken records, puffs of hair, some plaster, and wires. Over a meter wide, the piece looked like birds in flight, or (had it been a tenth the size) the sort of hat Audrey Hepburn might have worn perched on her coifed head in one of her ingénue 1950s movies. Move over, Audrey Hepburn, we have new ideas of beauty. Hammons always surprises with the ways he can make gracefully stunning the quotidian detritus of our lives.

The catalogue of the exhibition (the lead author is Kelli Jones) reproduces the works of the artists in the show, but it also includes “Friends.” These artists merited inclusion to extend the constraints of geography and race—to showcase also the artists who influenced or hung out with the L.A. black artists, including Joe Overstreet and Raymond Saunders from Northern California and Mark di Suvero and John Altoon who are/were not African American.

So Day #1 ended, with thoughts and images still buzzing in my head. I retired to my nephew’s vacant condo overlooking some Santa Monica motels and restaurants, with a narrow wedge of the beach and crashing surf in the distance. Ah…Lala-land!

©Patricia Hills, 2012

Letter Number Three