A Superb Revival of R. C. Sherriff's World War I Classic Journey's End

A Twentieth-Century Triumph of Death

By: Michael Miller - Mar 20, 2007

Heere is my iournies end, heere is my butt

And verie Sea-marke of my vtmost Saile.

(Shakespeare, Othello, Act V, sc. ii)

And verie Sea-marke of my vtmost Saile.

(Shakespeare, Othello, Act V, sc. ii)

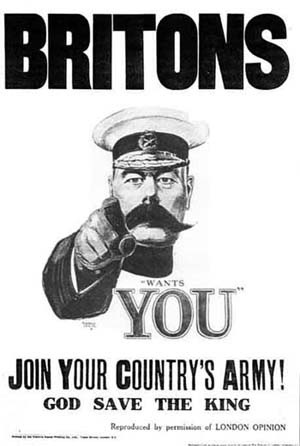

Before I go any further, let me say that the Broadway production of R. C. Sherriff's classic World War I play, Journey's End at the Belasco Theatre, is not to be missed at any cost, even if you have to brave the Taconic Parkway in a blizzard or get stung with a Manhattan parking ticket. Director David Grindley, who was responsible for the immensely successful London production, which ran for over two years in the West End and went on two national tours, sensibly understood that Sherriff's realist masterwork is no period piece, requiring no condescension, updating, or manipulation of any kind. The production owes its success to the directness and honesty of the play, which remains as powerful as when it first opened in 1928. All Grindley and his excellent, almost entirely American cast have to do is mind the details. The only contemporary interventions in the production are a curtain painted with the famous recruiting poster of General Kitchener fingering out prospective recruits, and a memorial wall covered with names of the dead, against which the cast take their curtain calls. These may edge it somewhat in the direction of an anti-war message—which was in fact not the intention of the author—but not stridently so, and they were effective in their own right. Kitchener's iconic summons to arms both sets the period of the action and tranposes it into the present, and the memorial wall adds solemnity to the conclusion and brings the evening's grim entertainment into a universal dimension. It is hard for a realistic and honest treatment of war not to carry a pacifistic subtext, but, I believe, it is precisely the tension between Sherriff's realist aesthetic and its inevitable implications that make Journey's End so fascinating after more than seventy-five years. It was, almost surprisingly, this anniversary and not the current war which inspired the 2004 London revival, not to mention the 2005 production at the Shaw Festival at Niagara-on-the-Lake. There is something almost miraculous in the freshness of Journey's End. It has been called a "minor masterpiece;" it is possibly time to forget the qualification.

The duality I have mentioned was apparent to Sherriff himself at the very beginning of the enterprise. As he said of Maurice Browne, the producer who eventually took up Journey's End:

What made him fall for the play was a mystery to me then and has remained a mystery ever since. It was totally unlike anything he had produced before, and the sentiments of the characters towards the war were in absolute contrast with his own. They were simple, unquestioning men who fought the war because it seemed the only right and proper thing to do. Somebody had got to fight it, and they had accepted the misery and suffering without complaint. But Maurice Browne was a pacifist, a conscientious objector, who flatly declined to have anything to do with the war. He remained in America while it lasted, and didn't come home till it was over.

In essence Journey's End was a backward-looking work. It brought dire memories to life and helped many to come to terms with them. Audiences were entralled because Sherriff had captured what life and death in the trenches was like: the waiting, the boredom, the measuring out of time in discrete parcels, the filth and stench, the constant presence of danger and death. Sherriff's disarmingly modest statement of his methods is worth quoting in full:

The experienced West End managers...had all done their best to get war plays across to the public, and all without exception had failed. The only thing they hadn't taken account of was that Journey's End happened to be the first war play that kept its feet in the Flanders mud. All the previous plays had aimed at higher things: they carried "messages," "sermons against war," symbolic revelations. The public knew enough about war to take all that for granted. What they had never been shown before on the stage was how men really lived in the trenches, how they talked and how they behaved. Old soldiers recognized themselves, or the friends they had served with. Women recognised their sons, their brothers or their husbands, many of whom had not returned. The play made it possible for them to journey into the trenches and share the lives that their men had led. For all this I could claim no personal credit. I wrote the play in the way it came, and it just happened by chance that the way I wrote it was the way people wanted it.

Journey's End comes as more of a rediscovery on this side of the Atlantic than in the UK, where it appears at least to have remained in print over the years and certainly stayed in people's memory. Once, in the late 1960's, as Sherriff's distinguished career as a playwright and screen writer was winding down, he was attending a reception at a local school, where "an old lady...said, 'I did enjoy Journey's End, Mr. Sherriff. Why don't you write something else?'" Even though he had written more than a few successful plays, novels, and screenplays (Goodbye Mr. Chips, That Hamilton Woman, The Dam Busters), he couldn't "shake off that label." In New York, after its initial run of 485 performances at the recently demolished Henry Miller's Theatre in 1929-30, it enjoyed only one brief revival in 1939. Let us hope that the absorbed and plentiful Friday night audience of the performance I attended presages a long run.

It was a miracle of sorts that Journey's End was produced at all. When insurance agent Robert Cedric Sherriff—a former captain in the 9th East Surrey Regiment, who was wounded at Passchendaele—first offered it to his agent in 1928, war plays were considered box office poison, as the agent pointed out, adding, "but we are enthusiastic about Journey's End, and we shall do everything possible to secure its performance." It was only with extreme difficulty that they managed to arrange two performances by the Incorporated Stage Society, a private theater club with a reputation for extreme intellectuality. The next challenge was to cast the play, particularly the principle role of Stanhope. Usually the Society had little trouble in attracting first-rate actors, but Journey's End, with its all-male cast and grim story, was turned down by a string of prominent actors before the young and still obscure Laurence Olivier accepted the part, thinking it might position him for the plum role of Beau Geste in a stage adaptation then in preparation. (He was right. He won the part and was unable to continue as Stanhope in the West End production that followed.) It seems almost a gesture of fate that Journey's End brought together a group of obscure young men of the theater, and its eventual success shaped their future careers. Laurence Olivier and Maurice Evans, who played Lieutenant Raleigh, both went on to the very top of their profession. Olivier's replacement, Colin Clive, enjoyed as much success as a film actor as his alcoholism would allow. The director James Whale—like Sherriff, a veteran of the war—followed the play to America, directing its Broadway and Chicago productions and eventually the film, which was made in Hollywood by a British company, went on to become one of the major directors of the 1930's. Sherriff himself became a top screen writer, both in Hollywood and at home. Success eluded only Maurice Browne, whose idealistic devotion to classical theater kept him a poor man for the rest of his life.

It was this idealism which brought him to Journey's End in the first place. Although the club production received rave reviews from all the London critics, no West End producer would touch the play. Only Browne, who had just returned to London after an unsuccessful attempt to create an audience for Greek tragedy in America, was sufficiently quixotic to take on the play, and he had a backer. To everyone's astonishment Browne's production, which at Sherriff's insistence included the entire cast of the club production except Olivier. Sherriff and Whale thought the teamwork of the young, little-known actors could not be surpassed, and even if they could have gotten a star to take over Stanhope, they wanted an unknown in order to avoid disturbing the balance they had created. The search was as difficult as before. Eventually a friend of Whale's recommended Colin Clive, a total unknown, who seemed to have an intuitive grasp of the part, although his intensity and nervousness made him freeze up and forget his lines. It was Sherriff who, as the opening night grew near, advised Clive, who was not a great drinker at the time, to medicate his nerves with a few stiff whiskies at lunch. While this one infraction of an unwritten law of the theater loosened his inhibitions and he never used drink again—for that purpose, according to Sherriff, it was a precursor of the alcoholism which was to kill him only eight years later. Sherriff said, "Clive's performance was magnificent: more rugged and restrained than Olivier's, but deeply moving, for the actor, like Stanhope himself, was straining every nerve to the utmost limits of endurance to fulfil his task." Sherriff also stressed two points about the play: first, its foundation in realism, and second, the towering importance of Stanhope and the absolute necessity of casting the part with a very strong actor. Clive truly owned the part, and when he left the production for a few weeks to act in the film, ticket sales dropped off severely, hastening the end of the run.

James Whale was in fact a jack-of-all trades in the theater. Trained as an artist, he was introduced to the theater as a prisoner of war, when he organized entertainments for his fellow inmates. When he was demobbed he established him himself in a variety of theatrical jobs: set designer, scene painter, stage manager, actor, director and so on. As a director he made a name for himself by staging the first successful British production of Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard—a work previously believed to be unplayable in English—by presenting it as a dark comedy. One of his first contributions to Journey's End was the set he designed. Sherriff was amazed when he saw Whale's meticulously constructed set, in which leaning beams created an expressionistic effect, conveying the oppressive weight of the battlefield over the British officers' underground lair. He confessed that he had never visualized his characters' environment in such physical detail. In this production, Jonathan Fensom's striking set, inherited from the London production, projects an equally disturbing claustrophobic feeling through its shallow height and depth, as well as its generally cramped dimensions.

When Whale prepared the film production he eventually decided on a script which remained close to Sherriff's original, incorporating a few cuts and "ventilating" the play with scenes in the trenches and the raid, which happens off-stage in the play. This decision, as well as the involvement of Whale and Clive, give the film some authority as a document of the West End production. A comparison of the film (which is in the public domain and turns up every now and then on wretched homemade DVDs) with the work of David Grindley and his cast, is a fascinating indication of the change in theatrical taste over the last seventy-five years. I wish I could say it was for the better, but I am reminded of Thomas Mann's lament, when he reminisced about a performance of Ibsen's The Wild Duck he had seen before the First World War. For him it embodied a subtlety which he felt had been forever lost in the conflagration. Of course R. C. Sherriff is not an Ibsen...but more of that later.

One contemporary critic observed that Journey's End is almost plotless, but that is an exaggeration. It begins in a dugout on the front line near St. Quentin on the evening of Monday, March 18, 1918, three days before the Germans launched their massive Michel offensive, in which hundreds of thousands of Allied troops were killed. We know the fate of all the characters. Captain Dennis Stanhope, who cannot be much older than twenty-one, is the extremely capable commander of this company, as we learn from Lieutenant Osborne, a middle-aged schoolmaster. However, under the strain of unrelieved combat duty, Stanhope has taken to drink. While he is able to exercise his duties with unfailing devotion and focus, he is falling to pieces as a man. A new officer, Second Lieutenant Raleigh arrives. We learn that he and Stanhope were friends at school. Three years younger than Stanhope, Jimmy Raleigh admired his friend's sportsmanship and leadership, the very qualities which have made him such a fine commander. We also learn that Stanhope is everything but engaged to Raleigh's sister. Jimmy, fresh from school, is thrilled to have been placed in Stanhope's company, but Stanhope, when he returns from duty in the trenches, is appalled to see his admiring friend and receives him coldly, even with hostility. Not only is he mortified to be seen by Raleigh in his present state, he fears that he will report it to his sister. He dismisses his friend contemptuously as a "hero-worshipper." Osborne, whose humanity and status as a schoolmaster exercise some influence on the two young men, provides Raleigh with comfort and support and functions as an intermediary between them. Sherriff, who derived the story from a novel he had written about the relationship between the two young men, has indirectly hit on the particular relationships on which the ethical formation of the English leading classes was founded: the humanitas and moral authority of the schoolmaster and the loving admiration of a younger boy for his senior peer. In the war the older generation is slaughtered, and the friendship of the younger men is undermined by the deterioration of human character under the ultimate stress—immersion in the inevitable death of one's comrades. As the German attack approaches, the high command orders Stanhope to send Osborne and Raleigh on a raid from which it is obvious that few will return. Only at the very end of the play is Stanhope able to restore his relationship with Raleigh through his deeply felt sympathy. Once again they can call each other by their Christian names, but there is of course no future in it. For a few minutes, this tragic situation allows Stanhope to be a complete, feeling human being again, before he is called up to the trenches to face the German onslaught.

The way in which the play is constructed on the relationship between the three men, shows why Sherriff considered Stanhope to be pre-eminent among the other, extremely vivid characters. The balance among the three is crucial. While Osborne in Whale's film exercises his influence more through his humanity than through any overt assertion of leadership, the superb American actor Boyd Gaines makes him a more imposing sort. His strength and leadership are close to Stanhope's and shore them up in difficulty. When he is killed in the raid, the film projects Stanhope's wrenching emotions and our own sadness at the loss of this fine man, but on Broadway we feel a gaping abyss in the social fabric as well. Without him Stanhope's relations with his junior officers become all the more desperate, not only with Raleigh, but with the malingering Second Lieutenant Hibbert, brilliantly played by Broadway newcomer Justin Blanchard. Stark Sands, who is also making his Broadway debut, projects Raleigh's naive enthusiasm admirably and even bears a slight physical resemblance to the young Maurice Evans. Playwright-actor John Ahlin makes does a fine turn as the down-to-earth Trotter, and so does Jefferson Mays as the cook/batman Private Mason. This production is certainly a feather in the cap for everyone concerned, and I have never seen an American company so comfortable in the ensemble playing at which British and European actors excel. No one is below the high standard they set as a team. However, if there is a weak link anywhere, it is the single English actor in the cast, Hugh Dancy. Perhaps I wouldn't be writing this, if I had not seen Colin Clive in the part, but occasionally Dancy's striving for intensity becomes rant, or even hysteria. When one compares his emotional outbursts with Clive's quiet control, he appears to lack weight and depth. However, I intend this only as mild criticism of a fine effort which is in general more than adequate for this extremely challenging role and barely compromises a powerful evening.

I could not help feeling, however, that the crucial final scene was somewhat compromised by Dancy's and Sands' emotive outbursts, which, together with the excessively loud recorded sound effects, distracted from the intense concentration of this final encounter between the two friends. When Sherriff indicates a sigh, Sands emits an agonized groan, which brings the scene down to a more visceral level. A New York audience in 2007 may need this added emphasis, but the quiet intensity of Whale's direction is so much more moving and to the point. What's more, Stanhope, as played by Dancy, appears to snatch wildly at humane words and gestures without really succeeding in realizing his emotions, much less his deepest feelings. It is surely essential to Sherriff's intent that Stanhope is here fully conscious of his feelings and is fully in touch with his wounded friend. Sherriff's own description of the opening night performance explains it:

During the last quiet scene before the final curtain I felt that the actors were holding on too long, playing too confidently upon the concentration of the audience. I could have shouted, "Get on with it! Get on! Finish and get the curtain down while the going's good, while you've still got the audience in the palms of your hands!" But the actors knew their job: they played upon the tension they had built up through the evening, and used it to the full.

If Stark and Dancy were not on this level, it still made its effect. When the lights went up, I saw a big tear running down the cheek of the lady sitting next to us.

Don't miss this excellent production. Go back and see it twice or three times. I certainly hope to. Meanwhile a Sherriff renaissance appears to be underway. One of Sherriff's novels, The Hopkins Manuscript, in which the moon leaves its course and collides with the earth, has been re-published by Persephone Books in the UK as a cautionary tale anticipating our current issue of global warming. Although Sherriff certainly didn't consider himself a political writer, it is interesting that his works have their way of floating to the surface in the shadow of some urgent public issue.

Sherriff's collaborator James Whale is also due for a renaissance of his own. It would certainly be a splendid thing if the film of Journey's End were released in a DVD of the best possible quality. Most interestingly Journey's End enjoyed great success in Germany as Die Andere Seite (The Other Side), and a film was made of it in 1931. (In fact, as David Grindley observes in his production note, there were seventeen productions playing in translation on the Continent in 1929.) I haven't seen it, but it is said to have stressed an anti-war Tendenz quite strongly and was heavily censored in many parts of Germany. A double feature release would be a perfect project for Kino International, and I'll see that someone in their management reads this.

___

The citations of Sherriff are taken from his memoir, No Leading Lady, London, 1968.

___

web: http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

email: michaeljames48@gmail.com