The Taming of the Shrew

Ft. Lauderdale's Thinking Cap Theatre

By: Aaron Krause - Mar 26, 2024

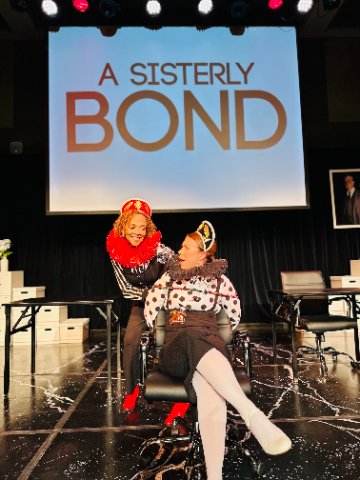

Thinking Cap Theatre (TCT) deftly brings William Shakespeare’s early comedy, The Taming of the Shrew (written between 1590 and 1592), into the 21st century with its solid professional production. It runs through April 3 in Ft. Lauderdale. Specifically, the venue is Broward Center for the Performing Arts’ intimate Abdo New River Room.

Certainly, the professional, nonprofit company’s imaginative, playful, accessible, and believable mounting gives the show a satisfying ending. It is probably more palatable to most modern-day audiences than Shakespeare’s sexist conclusion. In addition, TCT Artistic Director Nicole Stodard, who helmed the production and adapted the play (while keeping Shakespeare’s language), gives outer frame play character Christopher Sly a stronger purpose for existing than the Bard did.

But more on that a bit later. First, some background may prove helpful for those who slept through Shakespeare (1564-1616) in high school English.

The Taming of the Shrew is one of Shakespeare’s earliest and most popular comedies. One possible reason why is that directors often stage the relationship between Petruchio and Katherina as a lively battle of the sexes. Fortunately, that is the case with TCT’s staging, although the battle looks more playful than physical. Indeed, you never worry that the actors playing these roles will, for instance, severely scratch each other or tear each other’s hair out.

But before we see Kate or Petruchio, Shakespeare begins The Taming of the Shrew with an outer frame play. In the original one, Sly is an ignorant, drunken rustic. A group of aristocrats trick him into thinking he is rich. In Sly’s inebriated state, he watches a play put on by a troupe of actors. The play is the one we are about to experience, The Taming of the Shrew.

You might wonder about the purpose for Shakespeare’s outer frame play. But in TCT’s production, the purpose is clearer. Instead of an ignorant rustic, in TCT’s production, Sly is a company CEO. In addition to possessing a drinking problem, he may be a misogynist in need of sensitivity training. And, so, the company that he heads, Sly Enterprises, hires a troupe of actors to mount a production of The Taming of the Shrew. For the company’s employees, the play is an exercise in Diversity, Equity & Inclusion training, so it’s designed to benefit more people than CEO Sly. As part of the exercise, the company’s employees portray the characters in The Taming of the Shrew while Sly observes.

At the start of the show, even before the outer frame play begins, the players whom Sly Enterprises hired advertise their services. Also, they explain that a button exists that employees can push in the event that a scene in The Taming of the Shrew makes them feel triggered or uncomfortable.

When someone pushes the button, a shift in power occurs. For example, someone pushes the button for the first time after the marriage of Kate and Petruchio. It directly follows Petruchio’s famous speech during which he describes Kate as his “chattel,” an object of possession. This is a last-straw moment for this production’s Kate. Therefore, she presses the button. As a result, following intermission, a shift in power occurs. Specifically, the actors playing Kate and Petruchio in Act one have switched roles. This empowers Kate to walk in Petruchio’s shoes, while the actor playing Petruchio is disempowered and therefore forced to play subservient Kate. But there’s a problem. Namely, CEO Sly does not like this change. So, he pushes the button near the end of the play. This restores the actors portraying Kate and Petruchio to their original roles in act one.

The button also makes Katherina a stronger character by empowering her at the end. Many scholars and practitioners have criticized the play’s ending. Frankly, they wished for a better ending for Katherina than the final subservient monologue she delivers. The monologue, which Kate delivers after she obeys Petruchio’s command for her to instantly come to him, has presented modern-day directors with a challenge. In particular, how do they stage a play that ends with Katherina’s advising other wives to, among other things, “place your hands below your husband’s foot” if he should require it?

There are theories about the intent behind the monologue. One says that Katherina is being sincere; Petruchio has, in fact, tamed her and she has become his subservient wife. Contrastingly, another theory holds that Katherina is being sarcastic; she doesn’t mean a word of the monologue. In fact, she has duped Petruchio and others into thinking that he has tamed her.

Clearly, in TCT’s production, Katherina doesn’t mean what she says in the final monologue. Indeed, before the character (a strong Karen Stephens) delivers the speech, she huddles with a group of other women as though they are discussing strategy. Then, with her face betraying a cunning expression, she delivers the speech in an ironic tone. Following that, the character pushes the button, and by doing so, she avoids the traditional ending that Shakespeare wrote.

Without a doubt, TCT’s production is a feminist take on Shrew. And that is not surprising. According to its mission statement, TCT is a professional, non-profit company that “champions equality and theatrical experimentation and strives for excellence on and offstage. TCT is devoted to staging thought-provoking, socially-conscious, formally innovative theater and to gender and sexual parity in programming.”

Overall, this production is solid. It invites audiences to ponder how gender and power operate in The Taming of the Shrew and how this compares to gender dynamics in 21st century workplaces. Also, the use of the “button” helps Katherina and Petruchio see things from each other’s point of view. This humanizes them more.

From the actors’ fine work to the behind-the-scenes artists’ obvious skill, all production elements successfully combine to convey Stodard’s vision.

Speaking of Stodard, her careful direction gives the actors freedom to playfully portray their characters, befitting this popular Shakespearean comedy. Also, the pacing is just right; it never speeds or drags. We are able to clearly follow along, which is important when an audience experiences a Shakespearean production. Still, it wouldn’t hurt to read a summary of the play, or even the script before experiencing the production. Simply put, Shakespeare’s language can be challenging.

Unquestionably, the actors not only clearly and confidently speak this language, but credibly convey emotions and meaning behind the words. In fact, it sounds like their everyday speech. Also, the actors seamlessly pair spoken words with appropriate gestures and emphasize words when necessary.

Noah Levine, speaking in a deep, rich voice, gives us a larger-than-life and comical, commanding Petruchio. Levine also succeeds as a more submissive character when a shift in power occurs, forcing him to play Katherina. Specifically, he lowers his voice and his body language suggests someone more submissive than Petruchio.

Speaking of him, one may wonder whether Petruchio is comical or menacing based on his words and actions. Certainly, Levine’s playful portrayal tilts toward the comical end. In fact, his Petruchio could use some sternness at times.

Opposite Petruchio, Stephens makes a sly Katherina who is also rebellious and loud. With one eyebrow higher than the other, Stephens’ facial expressions aid in her character portrayal. And, like Levine, Stephens skillfully handles the shift in power.

Meanwhile, Melissa Ann Hubicsak, as Katherina’s milder younger sister, Bianca, is noticeably less intense and more polite than her older sibling. However, what could improve Hubicsak’s portrayal even more is a sense of yearning and frustration; after all, the sisters’ father has insisted that Bianca cannot marry until Katherina has a suitor. And, before Petruchio steps into the picture, how likely does it seem that the shrewish Katherina will ever get a suitor?

As Lucentio, the young student who wishes to marry Bianca, Phillip Andrew Santiago is a believably eager young man.

A wide-eyed Bill Schwartz, resembling Christopher Lloyd, is credibly unsteady as the drunken Sly. Unfortunately, Stodard places him in a space onstage that makes it hard to notice his reactions as he watches the play unfold. Also, it wouldn’t have hurt to include a scene taking place during an average workday in Sly’s company. It would have allowed us to see how he mistreats his female subordinates and how much he needs sensitivity training.

Interestingly, Stodard casts a female performer in the role of Baptista, a man. As Baptista, Beverly Blanchette maintains a formal, honorable demeanor and could pass for a male.

Behind the scenes, set and prop designer Alyiece Moretto-Watkins has designed a simple set with enough detail that resembles a real office.

Also, backstage, lighting designer Bree-Anna Obst, Thinking Cap’s managing director, includes a neat lighting effect when one of the characters presses the button. Obst’s lighting design includes a wise use of colors, especially red. Obst also designed the projections, which are simple and appropriate. For instance, they set us in a specific location. “Petruchio’s House,” in big letters, for instance, lets us know where a scene takes place without having to include many set pieces. And “Tutors Get Schooled” succinctly lets us know what is happening in a scene.

Stodard and Obst designed the sound. It allows us to not only hear, but understand the actors. And Stodard designed the costumes. They include dark suits, which seem appropriate for company workers. In addition, the actors wear capes, which help to define their character in the play-within-a-play (The Taming of the Shrew), not the outer frame play.

There is much to like about The Taming of the Shrew. With its rich and witty imagery, energetic verbal exchanges, as well as puns, disguises, double entendres, and a playful, competitive aura, audience members are in for a comic treat that doesn’t merely contain empty calories. The play, and this production of it, makes us think about gender and power dynamics in our own lives.

Shakespeare’s keen insights into human nature, his complex characterizations, and his mastery of language make the Bard one of the world’s best playwrights, if not the best. If you’re new to the Bard’s work, seeing a light, accessible play such as The Taming of the Shrew is a good starting point.

IF YOU GO

WHAT: Thinking Cap Theatre’s adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew.”

WHEN: 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday and a 7:30 p.m. performance on Monday, April 1, through April 3.

TICKETS: $45 general admission and $25 for students, not including fees.

WHERE: Abdo New River Room at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts, 201 S.W. 5th Ave. in Ft. Lauderdale.

INFORMATION: Call (954) 462-0222 or go to BrowardCenter.org. You can also find tickets at www.ticketmaster.com/thinking-cap-theatre-taming-of-the-tickets/artist/3059551?brand=broward&venueID=107373.

RELATED EVENT: A reading of John Fletcher’s play, The Tamer Tamed, Or the Woman’s Prize, a response to Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.” The reading will start at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, April 25 at ArtServe, 1350 E. Sunrise Blvd. in Ft. Lauderdale. For tickets, go to The Tamer Tamed or The Women’s Prize | Play Reading Tickets, Thu, Apr 25, 2024 at 6:30 PM | Eventbrite.