The Dawn of Egyptian Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Through August 5

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 19, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has mounted a rare and intimate selection of often small, jewel-like artifacts and works of art from the predynastic era The Dawn of Egyptian Art through August 5.

It is usual to consider Ancient Egypt as divided into three major periods- Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom- with thirty dynasties starting around 3,100 BC and ending with the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC.

That’s the simplistic version and about as much as most students learn in one or two lectures during a survey course on the Art of the Western World.

Few if any college art history programs offer courses focused on Egyptian art despite that formidable 3,000 year long legacy. The Eurocentric norm is to assume that the real history of Western culture begins with the classical era of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

No educated individual of my generation escaped from higher education without reading the Iliad and at least Oedipus Rex. Many moved on to read The Odyssey, more Greek plays, or even a bit of Roman literature. As a school boy I labored through six years of Latin including Caesar, Cicero, Virgil and a bit of Ovid. Now mostly evaporated through a lack of use.

Here’s a simple question. Have you ever read the Egyptian Book of the Dead? No! I thought not. Need one even bother to ask if you have read the Tibetan Book of the Dead? Or The Bhagavad Gita?

Ok. I know. You’ve read The Bible cover to cover. Unless, of course, you are Catholic. And most if not all of Shakespeare’s plays.

The point is that, other than shows on the History Channel, a little about King Tut, and perhaps the Philip Glass opera Akhnaten, most people are fairly clueless about the magnificent and remarkably enduring civilization of Ancient Egypt.

Including, it seems, New York Times critic Roberta Smith who outed herself while reviewing this superb special exhibition. In the midst of describing some of the 190 objects from 3900 to 2649 BC she states the “… They include about 80 works from the Met’s collection, most of which usually hide in plain sight, on display in the opening gallery of the Egyptian wing, which tends to be the one we speed through on our way to all things Pharaonic.”

Prior to the assignment to cover this special exhibition curated by Diana Craig Patch, associate curator of the Met’s Department of Egyptian Art, one assumes that in her rush to see the works of the museum’s renowned New Kingdom collection, Smith never gave these mostly small and exquisite works so much as a sideways glance.

Which appears to be the point of the jewel like installation, of numerous, individually illuminated virtines in the difficult, narrow, circular gallery of the lower level that surrounds the atrium of the Robert Lehman Wing. The curator has attempted to render the seemingly invisible and ephemeral work of the early period more accessible to museum visitors.

The approach is to emphasize the aesthetics of the objects with small, dense and didactic labels for those inclined to read the small print. There are, however, none of the maps, time lines, videos and enlarged text panels that normally accompany installations of such esoteric, rarely celebrated material.

Without sufficient educational materials to support the objects, the general public encounters the work as ancient, beautiful, somewhat naturalistic artifacts. While 3,500 BC may seem terribly old where does it configure in the timeline of Western Art and compared to what?

The current installation represents a paradigm shift in museology. The great collections of ancient art in The Louvre, British Museum, the museums in Berlin, and yes, even the Met and Museum of Fine Arts Boston tend to display a jumble of archaeological specimens. In the case of the British Museum and Louvre, the results of Colonialism, and the conquests of Napoleon. The founding concept of these great museums was to stash the loot as emblems of national pride.

Need we remind you that Lord Elgin was a thief who robbed the Greeks of their greatest treasure, the sculpture that he stripped from the Parthenon.

American museums, for the most part, acquired their Egyptian collections honestly through digs with permits and cooperation, including the division of finds, with Egyptian authorities. The host nation lacked the resources for extensive and expensive excavations.

As Smith points out in the dense, chockablock galleries of the Met’s extensive Egyptian Collection, it is daunting for most visitors to distinguish the forest from the trees. There is nothing that guides us to identify masterpieces among the ephemera.

That’s why it is so riveting to experience the Amarna period masterpiece, the polychromed portrait of Queen Nefertiti, in Berlin. The object, arguably the single most beautiful sculpture from all of Ancient Egypt, is given breathing room in its own gallery. The vitrine that contains her is the centerpiece of a dark room, brilliantly illuminated. To encounter her is a stunning and unforgettable experience.

In the 2010 film by Werner Herzog Cave of Forgotten Dreams, we are introduced to the recently discovered Chauvet Cave in the South of France. Using carbon testing of organic materials the naturalistic paintings on the walls were created as early as 35,000 BC. There is another group of paintings that were produced around 27,000 to 26,000 BC.

Remarkably, the images in the Chauvet Cave are far older than the cave paintings in Lascaux which are dated to around 15,300 BC.

The cave paintings are so rare and fragile (now damaged by black mold) that they are closed to all but a handful of scholars and scientists. A replica cave has been created near Lascaux which is open to tourists.

A compelling question is just who were the predynastic Ancient Egyptians? Neolithic sites from circa 6,000 BC have been identified all over Egypt. The assumption is that they were Semites who migrated from the Fertile Crescent. There is evidence of conflict and conquest among descendants of migrant groups and indigenous Africans.

Two of the seminal objects that document that aspect of the early period- The Gebel el-Arak Knife Pre-historic Egypt, Naqada II (3500-3100 B.C.) in the collection the Louvre and, from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonopolis Palette or the Palette of Narmer, circa 3100 BC- were not included in the Met exhibition. The Narmer Palette was referenced in a photograph but the ivory and flint knife was not.

Arguably, the curatorial strategy was to highlight the beauty of the selection of objects and not present an elaborate and complex history lesson.

Both the elaborately carved ivory knife handle and slate palette present graphic, gruesome images of war and slaughter of enemies. During all periods of Egyptian art conquest scenes are explicit in depicting physical differences, the distinctive clothing and accessories (including weapons), of the enemy or ‘other.’

The didactic point of the Narmer Palette, in which the Pharaoh looms in scale over all others, is that he conquered and united the two lands, or kingdoms, of Upper and Lower Egypt. His defeated enemies are symbolically represented as a pile of corpses with their decapitated heads as objects between their splayed legs.

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston is noted for depth in art of the Old Kingdom. When the area around the Pyramids of Giza were excavated there were four international teams which drew lots for their permits to dig. George Andrew Reisner of the MFA found a trove of treasure around the smallest of the three pyramids dedicated to Menkaure (or Men-Kau-Ra; Mycerinus in Latin; Μυκερινος, Mykerinos in Greek). He was a pharaoh of the Fourth dynasty of Egypt (c. 2620 BC–2480 BC).

The excavation yielded the oldest know true portrait; the polychromed, limestone bust of Prince Ankh Haf. The museum also displays a group of life sized, limestone “reserve heads’ representing members of the royal family. While not “portraits” to the degree of the Ankh Haf they convey the generic features of individuals. One princess has well defined Semitic features while another princess is distinctly black African. The other sculptures reveal the genetic blending of intermarriage. Out of which we find the generic Ancient Egyptian as idealized in the famous, slate, standing sculpture of Mycerinus and His Queen. She was one of several queens singled out for this great honor.

The objects in this Met exhibition are presented without bookends or footnotes. It makes one ask to what extent were they unique? Were there other, similarly advanced cultures? What if any were shared characteristics? To what extent did the creators of these early objects know of works from other regions surrounding the Mediterranean?

Largely through marine archaeology we are compiling more data about travel and trade in the ancient world. Egyptologists, for example, have excavated Minoan pottery from Crete. During the time frame of the Met show there were other advanced cultures creating works of art- Cycladic, Minoan, and Sumerian.

The oldest Western, written languages- Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics- appear on objects before 3,000 BC.

With the exception of the Amarna period of the heretic Pharaoh Akhnaten, Egyptian art, mythology, and culture remained remarkably stable and consistent. Even when conquered- by the Hyskos, Asiatic-Semites who seized power about 1630 BC, or the Nubians who conquered Egypt and established Dynasty 25 (760 to 656 BC)- the upstart dynasties quickly absorbed and continued embedded traditions. Cleopatra, the last ruler of the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty was rare in speaking the Egyptian dialect and respecting the ancient religion and customs. Even the Roman conquerors often opted to be mummified with the modification of attached, realistic Fayum portraits.

Although the emphasis is on the very early period at the end of the exhibition the objects fast forward without logic or warning. The Middle Kingdom Dynasty 12, blue ceramic hippo may be, as the New York Times article identifies it “an unofficial mascot of the Metropolitan Museum” but it makes no sense in the context of the exhibition. Perhaps the installers just ran out of material to display and needed some filler.

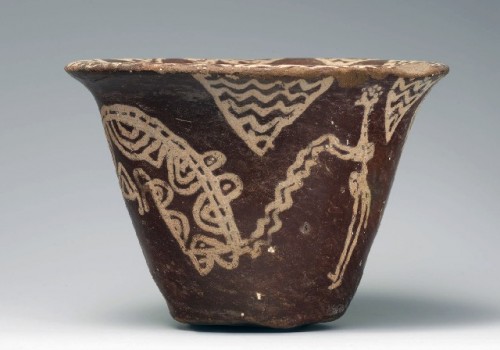

Without sufficient signage and support materials we are left to generic impressions based on the empirical evidence of the objects. There is an assumption that the oldest objects, from around 3,600 BC are the most simple and “primitive.” They represent the beginnings of the technologies of forming objects. There are coil technique ceramic vessels with slip clay painted or incised decorations. There is the stone age technique- not seen here- of chipping flint to make knives and carving objects. These are used to work with bone, ivory and slate to create simple artifacts.

If you follow the clues of the labels several centuries separate the earliest and most simple ceramics and carvings from the far more realistic and compelling objects of the early dynastic period. In this very compressed manner of conflating centuries of experimentation and progress we examine, in its embryonic stage, the paradigms of Ancient Egyptian art.

If the label information is accurate the oldest object in the exhibition appears to be Figurine of a standing woman Badarian (ca. 4400– 3800 BC) Provenance: el-Badari, Grave 5107 Ivory. Given her age and position as among the earliest works she is remarkably naturalistic despite a somewhat grotesque face.

There is no context to understand how this advanced degree of naturalism emerged full blown at that time and place. Are there older more rudimentary works that precede it? While the naturalism is impressive one must consider a lapse of thousand of years between this inception of Egyptian art and the creation of the Venus of Willendorf. That remarkably life like sculpture, unearthed in Austria, is dated at between 24,000 and 22,000 BC.

Why is there such an enormous gap of thousands of years between the Neolithic cave paintings, carved effigies and the dawn of advanced cultures during the sixth through third millennia BC? Will future archaeology connect the dots and fill in the gaps by providing a more coherent and complete overview of the artistic accomplishments of these early civilizations?

A step forward by several centuries from Figurine of a standing woman Badarian to Celebrant figurine (“Bird woman”) Naqada IIa (ca. 3650 BC) Provenance: el-Ma’mariya, Burial 2 is also a reversal from a technical and aesthetic vantagepoint. The simplistic ceramic bird woman is more “primitive” than its predecessor.

Another significant difference is that the first figure attempts to represent a naturalistic women while the latter is an anthropomorphic deity. Arguably, she is a bird with human characteristics. One assumes that it is a cult figure and the beginnings of ever more elaborate Egyptian religion and mythology. It became the norm that gods and goddesses combined animal and bird heads with human bodies. In that cosmology the sky is a goddess Nut and the Nile is a deity. The sun disk is the god Amun and its rays the essence of Ra.

Is it correct to assume that the Bird Woman represents the birth of those traditions? If so the object resonates with significance. But, again, we want to know more about the context of the peoples who created her, their intentionality, cults, ceremonies, and social organizations.

During later periods of Egyptian art we will have very explicit answers to all of those questions. On the walls of their mastabas the artists created vivid genre scenes. The intention being that during the after life the Ka of the deceased would live through eternity in familiar surroundings. In a tomb filled with food, furniture, clothing and jewelry to sustain the deceased through an endless journey.

The early examples of pottery are fascinating for their schematic paintings of Nile creatures or stylized barges with their multiple oars. The potters devised the simple technique- figure vs. ground- of working with two basic colors of clay a kind of buff ochre and a red oxide. Using thin, watery slip the color is applied to the vessel which becomes fixed when low fired.

In addition to ceramics the early Egyptians created numerous stone vessels in a great variety of materials including translucent alabaster and multi colored granite. Of this genre we are presented with a few of the numerous slate palletes and none of the vessels.

The slate palettes were functional and ubiquitous. They were used to grind kohl which when combined with water was applied around the eyes. Much as it is today. Perhaps it had the pragmatic aspect of reducing the intense glare of the sun. Today it is regarded entirely as a cosmetic.

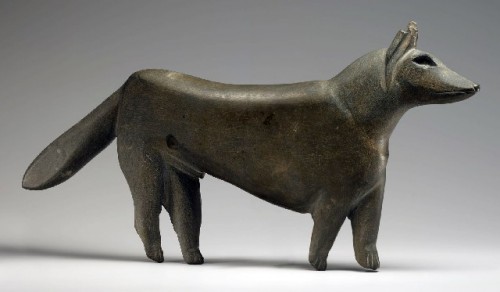

It is the norm to admire the “abstraction” of these artifacts with their decorative designs. The most stunning such example in this exhibition is Jackal statue Naqada III (ca. 3300 – 3100 BC) Provenance: el-Ahaiwa. The flat stone object has an amusing and compelling silhouette. There is a sense of an attempt to create an illusion of movement with the configuration of the legs. It was an experiment that did not prevail. But great fun to see it here.

Our appreciation of the contemporary like “abstraction” derives from reversing art history. Through the reductive sculptures of Brancusi, for example, we come to connect with the “modernism” of very ancient works like the simple, elegant forms of Cycladic sculptures. Yes, there is an uncanny resemblance but taken completely out of context.

Of course artists never obey these rules. Consider Picasso, for example, and how Oceanic and ancient Iberian art inspired him during the 1906-1907 development of analytical cubism. During an interesting incident, which Richardson conveys in his multi volume biography of Picasso, it seems that the artist and an accomplice (Guillaume Apollinaire) stole an Iberian sculpture from The Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. Allegedly, in a panic about being nabbed and deported Picasso chucked it in the Seine under cover of night.

It provides some irony to his statement that “Minor artists borrow wile great artists steal.” Indeed.

While we greatly miss the Slate Palette of King Narmer there are lesser but choice example of this genre of decorative carving- Ceremonial palette (The Four Dog Palette) Naqada III (ca. 3300 – 3100 BC) and Ceremonial palette (The Battlefield Palette) Naqada III (ca. 3300– 3100 BC) Provenance: unknown, possibly Abydos. It was a great pleasure to examine their intricate details.

Baboon statue Dynasty 0, reign of Narmer (ca. 3100 BC) Provenance: unknown, is singular in this exhibition for its size. It implies a technological advance in the ability to carve larger blocks of stone. One must consider the tools and techniques as they evolved. The later dynastic artists were able to carve works on enormous, colossal scale. In the example of Abu Simbel, created in 1257 BC to honor Pharaoh Ramses II, it entailed sculpting a sandstone cliff. (With the creation of the Aswan Dam it was taken apart and reassembled on top of its site at the edge of the Nile.)

Egyptian artists were also capable of carving the hardest granite with sublime subtlety as the wonderful Middle Kingdom Lady Sennuwy in the MFA. It is all the more remarkable considering they accomplished this using stone and copper tools.

Within the confines of this intimate survey there is a sudden great leap forward represented by Statuette of a standing man wearing a penis sheath Naqada III– Dynasty 1 (ca. 3300– 2900 BC) Provenance: Hierakonpolis, and Statue of a standing woman (The Lady of Brussels) Probably late Dynasty 2 (ca. 2695– 2649 BC) Provenance: unknown.

In these and other examples it is clear that by Dynasties One and Two (There is also a Dynasty Zero) all of the characteristics of a true Egyptian style, which will prevail for three millennia, were fully realized. Their naturalism/ realism are uncanny in closely observed details. These elements advance in representations of Zoser (also known as Dzoser, Zozer, Dsr, Djeser, Djésèr) in whose honor the Stepped Pyramid of Saqqara was created. It is attributed to the first known architect, Imhotep. This aesthetic reached its apogee during the art of Dynasty Four and the creation of the Pyramids of Giza.

With the exception of the proto mannerism of the brief heretic Amarna Period, one of the greatest accomplishments of Western Art, for me, Dynasty Four represents the paradigm of Egyptian Art.

The singularly most beautiful object in this exhibition is Statuette of a standing woman with crossed hands Naqada III– early Dynasty 1 (ca. 3300– 3000 BC) Provenance: Hierakonpolis. She was carved from a small, rich blue piece of lapis lazuli. It is suggested that the material may have been imported from Afghanistan. This scholarly hint speaks volumes about that daunting topic- trade circa 3000 BC.

It does not appear to be the intention of this exhibition to raise such questions or to provide answers. We are encouraged to just look long and hard at small and evocative objects.

Look not learn appears to be the mantra of this project. Is this progress in museology? The experience proved to be fascinating but also frustrating.

Dawn of Egyptian Art By Diana Craig Patch, with essays by Marianne Eaton-Krauss, Renee Friedman, Ann Nancy Roth and David P. Silverman; Contributions from Susan J. Allen, Emilia Cortes, Catherine H. Roehrig and Anna Serotta; 288 pages, 246 illustrations, including 234 in full color; map; selected references; chronologies; index; The Metropolitan Museum of Arts; Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London