Natchez, Mississippi's Mansions

Iconic Antebellum Architecture

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 30, 2014

When the Southern economy boomed during the era of King Cotton the community of Natchez, Mississippi, per capita, was one of the wealthiest in America.

The harvest of vast plantations in the region came to Natchez, named for the decimated indigenous Native Americans, to be shipped down river and sold in the markets of New Orleans.

Discussing the legacy of slavery it is usual to finger point to plantation owners. But in reality the cotton industry pervaded the American economy. It was the driving force in the cotton mills of New England including those in North Adams where we reside in the shadow of Mass MoCA. Local bankers and mill owners were directly involved in the slave trade and production of cotton.

This year’s Oscar winning film Twelve Years a Slave vividly depicted the horrors of forced labor.

So it was with mixed emotions and trepidation that we explored the rich architectural heritage of Natchez which was spared the torching of Atlanta and devastation of General Sherman’s scorched earth March to the Sea.

In 1861 the cotton crop was destroyed by Confederate troops rather than have it fall into the hands of the Union Army. It might have been sold to support the Northern cause. The following year the crops of Natchez area plantations were destroyed by the Union army. The back to back losses bankrupted the city from which it never really recovered. This configured Natchez as an architectural time capsule of the era. Today the many mansions clustered in and around Natchez generate a tourism based economy. There is also a classic river boat casino as well as a newer one.

From my graduate study of American art and architecture I had long wanted to visit Natchez. In particular to view the exquisite Longwood which has a fascinating and tragic history. It is illustrated in all of the standard textbooks.

We visited Natchez during the Easter weekend. That meant seeing Longwood and other mansions on Saturday as they were closed on Sunday. Arriving on Friday night we enjoyed the $14.95 seafood buffet featuring Alaskan King Crab at the somewhat seedy riverboat casino. Natchez has many fine restaurants which were closed that Sunday. We enjoyed the Easter brunch at a hotel adjacent to ours. After which, following a map, we conducted a self guided tour of the many mansions and run down neighborhoods of Natchez.

Our Best Western hotel was located overlooking the river and a vintage bridge leading to Vidalia in Louisiana. We crossed over and spent time in a beautiful waterfront park. The view of the Mississippi was spectacular and Astrid thought it was far better than our similar experience in New Orleans. It was particularly intriguing to see the traffic on the river. There were seemingly endless connections of barges with a tugboat on the end. Just as it was during the time of King Cotton the Mississippi is used to transport goods. It conjured the shade of Mark Twain and his tales.

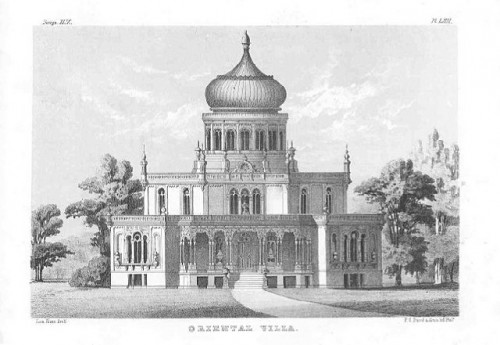

Dr. Haller Nutt, a non practicing physician, aspired to build a grand mansion that would be different than the neo classical homes of his wealthy neighbors. Based on an illustration of a fantasy octagonal home in a Moorish style he hired the Philadelphia architect Samuel Sloan. The design phase was completed in 1859. Kilns were set up to fire the vast number of bricks required for the ambitious structure.

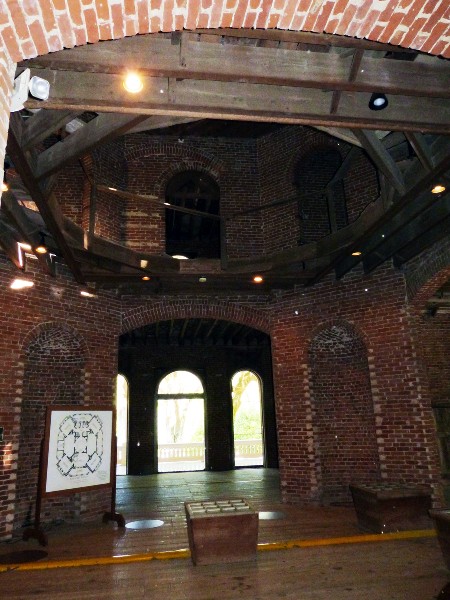

Augmenting a crew of slaves, described as workers and helpers by the guide, some 70 skilled craftsmen and artisans were recruited from Philadelphia. From the exterior the structure appears finished including the lead roofed cupola capping five stories. In all thirty-two rooms were planned. Had it been completed Longwood would be compared to Monticello on the short list of vintage great American homes.

When war broke out in 1861 the Philadelphia crew dropped their tools and returned home. The consecutive years of crop burnings left Dr. Nutt bankrupt. He moved his family into nine rooms on the first floor. Today they are furnished in period style with some surviving family heirlooms and portraits. No photography is allowed in that area of the home.

Exploring the upper level of the mansion it is still in an unfinished state. The experience of arrested construction proved poignant. The guide discussed the miseries of war and economic hardship of the Nutt family. Through a combination of stress and pneumonia Dr. Nutt died in his forties in 1864. It was up to his widow to manage affairs and raise their children.

Originally the mansion was sited on 150 acres. Reduced circumstances resulted in the sale of all but five acres. Longwood stayed in the family for generations in a state of disrepair. It was eventually sold, restored, and the original surrounding acreage was purchased. Once completed the private foundation gifted it to Pilgrimage Garden Club which maintains it as well as other historic properties.

The narrative of the guide seems scripted from Margaret Mitchell’s Civil War fantasy Gone With the Wind. Mitchell’s was the traditional master-centric version which has prevailed in the arts and literature since D. W. Griffith’s racist masterpiece, the silent film Birth of a Nation.

There was a chilling element of that as the guide described the hardships of the widow Nutt and subsequent generations. She pointed out a rare commissioned portrait of the loyal head of the household slaves and personal servant of Dr. Nutt. He remained with the family through and after the war and is buried in the family cemetery.

After the tour I discretely approached the guide and asked her how many slaves the family owned? It seems that Dr. Nutt owned five plantations in the area with a staff of between 400 and 800 “workers.”

Previously we toured Jefferson’s Monticello and the Hermitage of Andrew Jackson in Nashville. At Monticello there is no visible evidence of slave quarters but they survive on the property of the Hermitage. We have yet to visit the Mt. Vernon of slave owner and nation founder George Washington. But visits to these homes, while magnificent for their architecture, pay but lip service to the forced labor that funded them. We imbibe the inventive genius of Jefferson while scholars have revealed his deeply rooted Virginian racism. His documented remarks on the inferiority of blacks cast a grim light on the author of the Declaration of Independence.

Touring Southern cities in recent years one notes signage that documents the slave trade. One wonders when the Mill cities of New England will make similar recognition of their complicity in the slave trade and cotton based economy. There is another issue that these were the very mills photographed by Lewis Hine when he documented child labor in America. He photographed children in our Eclipse Mill which now houses 40 artist live/ work studios. The Eclipse Gallery hosted a traveling exhibition about child labor organized by the gallerist Ralph Brill.

Following the map we viewed many mansions. One of the most magnificent was Dunleith which is surrounded by a portico supported by Doric columns. It provided a wrap around veranda on the ground floor and balcony on the second. During the hot summer months one imagines family members seeking shade or stepping out of upper bedrooms to catch a breeze.

There was a wedding being prepared during our visit. The mothers of the bride and groom were tying broad satin sashes around the rows of chairs facing the entrance. Astrid joined in and helped while chatting with the women. The house which hosts such events was open so we were able to explore and photograph its period interior.

Like Longwood, Dunleith was surrounded by a spacious property. Driving around the city however the majority of the mansions were town houses. The wealthy families lived in Natchez with working plantations in the surrounding area.

Exploring neighborhoods there was a dramatic contrast between upscale streets with mansions and gracious homes and then a short distance away the small and often run down homes of the working class. More than a century after the Civil War the same social and economic divisions evidently prevail.

One wonders why African Americans opt to continue to live and work in such an environment.

We had lunch in the elegant dining room next to Stanton Hall. The hostess who seated us was rudely abrupt when we asked for a better table. The waiter was distracted and inattentive. Taking our order he rushed the process wanting to grab the menu out of my hand. I had to tell him that I was still deciding and asked for recommendations. Later when we needed things like a refill of drinks we had to flag down other waiters.

The experience was anything but gracious Southern hospitality. It seemed to convey that we were white people and our very presence in Natchez was an implied endorsement of its historical legacy. With that in mind we left a generous tip.

Continuing our architectural exploration I felt that my social gyroscope was spinning out of control. I lacked the Pavlovian distancing of native Southerners. There is an implicit decorum that the races and classes know their place. As a stranger to this complex culture it felt raw and unnerving.

Visiting Natchez is not really like a theme park Disneyland of the Old South. We are very pleased to have had the experience. It greatly contributes to an understanding of historic American architecture. But it was also a vivid signifier of the grim legacy of slavery, Native American (Natchez) genocide, and repression of minorities which continues to roil America’s moral compass.