Arnie Reisman on Boston Media in the 1960s

Boston After Dark Became Boston Phoenix

By: Arnie Reisman and Charles Giuliano - May 15, 2011

Arnie Reisman is an acclaimed video producer. He created the video elements for Boston by Sea and Innovation Odyssey, and is an award-winning writer, producer, and performer. He has worked in commercial and public television, corporate video, theater, and film. His national broadcasts include the documentary Hollywood on Trial, Public Broadcasting System's The Other Side of the Moon, and PBS's AIDS Quarterly. Reisman was also the coauthor of Teacher, a half-hour TV play that won the American Film Institute's special drama award. He has written six screenplays, coauthored WGBH's documentary, The Big Dig, helped develop WCVB's "Chronicle", and received five regional Emmys for other work at WCVB.

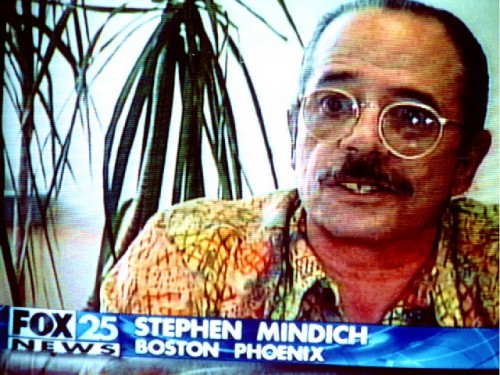

Charles Giuliano Discuss with us your tenure as editor of Boston After Dark, later renamed The Boston Phoenix, during its early years when it was entirely focused on arts and culture. This was when Stephen Mindich was partnered with Jim Lewis whom he later bought out.

How did you come to take the job? I recall those Saturday's at Misty's the hot type setter when we read proof. Or those long Friday nights when the paper was put to bed. For a brief time I joined the weekly as its design director.

Wasn't there a split between the two publishers before they settled their differences? Remember Public Occurrences? Much of that is now hazy. I recall meeting with the Mindich group and stating with some passion that there was a riot going on and we were not covering it.

At first there was just BAD but then Broadside/ Free Press, Ray Mungo and Liberation News, The Old Mole, briefly Avatar when Dave Wilson and I were editors. Then Cambridge Phoenix and I don't quite recall how the Real Paper got into the mix. Add to that the riots, protests, and cultural upheaval.

Arnie Reisman Ah, yes, the Sixties! The short answer is: I don't remember. Or, it was all a dream. Because if it really did happen and if all that upheaval meant something incredible had changed, then where did it all go? Why did the Sixties vanish into historical footnotes? Or just become a joke like Robin Williams' comment: "Anyone who really remembers the Sixties didn't live through them" (or words to that effect).

The Sixties didn't last much longer than the Beatles. The Sixties, as we know them, didn't really start until late 1966 or early 1967, and they ended either with the end of Watergate or the end of the war in Vietnam, about eight years later. Maybe they began in June, 1967, with the release of Sergeant Pepper. At any rate, you and I were both at Brandeis, Charlie, in the first part of the chronological Sixties, where you wrote about art for The Justice when I was the editor. Since I never really thought in terms of what I was going to be when I grew up, I reached my senior year in college and panicked. I mean I was one of those people who thought of who he was, not what he was. Career? What's that? Even today when someone asks me if I'm planning to retire soon, I have to respond, "From what?"

So, because I was happy running a little school newspaper, I opted for a journalism career. Got my masters from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and came back to the Boston area in June, 1965, to write reviews for The Quincy Patriot Ledger, a suburban daily that reached more than 30 towns on the South Shore. It was a great gig. Culture was my beat. I could cover all the arts, even the entertaining ones. So I wrote film reviews, theater reviews, music reviews, book reviews, TV reviews -- after all, there were only three arts reporters. My specialty was film. I lived for the movies. In six months on the job, they made me the arts editor. In my own little way I had power. I lived in Cambridge and told people what was really going on in the Greater Boston arts scene, cultivating tastes in more than 30 towns that had nothing to do with Cambridge.

In the fall of 1968 I got a call from Stephen Mindich, the co-publisher of Boston After Dark, a 16-page weekly giveaway about the arts scene -- reviews and listings and ads, that was it. Its appeal was to a young audience. The ads reached out to college students, because the publication was basically delivered to area campuses. Actually, Boston After Dark began as a supplement inside the Harvard Business School newspaper. Jim Lewis of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, was a student at HBS. When he graduated, he and an MIT colleague, Joe Hanlon, asked if they could spin off the supplement. They got it and opened an office in Boston in early 1966. As is the case with several other publications or programs I've been associated with, the Wikipedia entry on Boston After Dark/Phoenix (the Phoenix part I'll get to soon) is mostly inaccurate. Anyone who uses Wikipedia to gather "facts" should have his/her head examined.

By the time I got the call from Mindich, Hanlon was gone. Mindich, a BU grad from the Bronx, had come aboard selling ads. He and his ability soon became the backbone of the publication. Now he was Jim Lewis' partner. Steve asked me to lunch. We had crossed paths several times since he also served Boston After Dark as a theater critic, especially Broadway theater. We met or sat near each other at many a play in Boston. I was moonlighting as a theater critic for Variety, the show biz weekly, covering plays on their way to Broadway. Steve also caught me on WGBH's "counter-culture" experimental TV show, "What's Happening, Mr. Silver?" This local public television happening was a weekly attempt at trying to prove that the station was hip and offered something to a younger audience. The host was David Silver, who taught English at Tufts and was himself about three years out of college. What really made him marketable at the time was the fact that he was British. After I gave the only positive published review to the show, the producer, Fred Barzyk, called me and asked me to come to WGBH to help write the program. I not only did that but ended up on the show as your typical local gadfly.

At lunch Steve asked me to be the editor of Boston After Dark. I was 26, about a year older than Steve. He was losing his editor, who was moving away. After some affirming thoughts about running a small paper dedicated to the arts and entertainment, I said yes. Steve offered me more money than I was making at the Ledger and editorial control. I should have asked for a piece of the profits, but that's not the way my mind was working. My tenure as executive editor lasted three interrupted years, ending in the fall of 1971, during which time I was allowed to take the 16-page arts weekly and turn it into a 156-page news weekly. I quit primarily because I was exhausted, burned out. Why did we change the paper? What follows is the story that no one seems to get right.

I was more or less happy cruising along running an arts weekly. I wrote each week about a film or two. We were making many inroads, covering people and scenes not covered by the mainstream media. We were making a name for ourselves. As soon as I came on board, Mindich and Lewis decided to put out two versions of the paper -- one on newsstands away from college campuses, sold for 15 cents, and one given free to campuses. There were also subscribers, a gathering number outside Boston, and they would be charged the newsstand rate. But why would you pay if you can find a free copy? That was settled thanks to a silly loophole in the US postal code. Turns out to say you have two different publications, one 20% different from the other, you can use the bulk mail rate for shipping one of them. So we made two newspapers simply by manipulating 20% of the copy -- changing headlines, photos, layouts and using some stories in one paper that would appear the following week in the other paper. Hence, we had Boston After Dark on newsstands and B.A.D. on campuses.

Two critical events for BAD happened in the summer of 1969. The first was a call from another Brandeis grad, Jeff Tarter. He was a year younger than I and served as my news editor at The Justice. He went off to Vietnam and became a Time magazine reporter. He had seen enough and now felt there was another side to just about every story. Call it alternative media or advocacy journalism. He called me to say Boston could use a Village Voice, something to go up against the establishment (in politics and journalism) and offer another way of looking at things. I agreed. He told me he was putting together some investors and some family money and planned to open such a weekly in the fall. He asked me to join him and become his editor.

After that phone call, my brain was swimming. A news weekly sounded like a good idea. For the same reason BAD was. There's an audience in this town -- young, hip, college-educated, artistic, professional, whatever. There's definitely an audience. But can Jeff pull this off? In terms of life span odds, publications are worse than restaurants. Here's where I have to ask for forgiveness. As someone once said, justifying a questionable action, it's easier to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission. I projected that Jeff's chances were slim. So I went to Steve and said we should consider turning BAD into a Village Voice for Boston. Turns out he was savoring the same idea. But there was an obstacle. Before he could tell me about the obstacle, I told him about Jeff Tarter's plans. Steve's face changed. It got feverishly red.

This brings me to that second critical event -- the Mindich-Lewis feud. Turns out Steve and Jim were in a fight to the death for changing directions of the paper. Jim had created a parent company, YMI, Youth Marketing International. He wanted to have After Dark newsweeklies everywhere and started with Cleveland After Dark. Turns out not much was going on after dark in Cleveland in those days and the publication struggled, draining money from the coffers of BAD, which made Steve cranky. These two were never meant to be partners. I thought of joining Jeff but Steve asked me to hang on, because he felt somehow he could convince Jim to do a newsweekly. Their negative feelings for each other spilled out into the life of the paper. The staff felt the BAD vibes. Meanwhile, October came around and the Cambridge Phoenix was introduced. Jeff Tarter was the publisher. Lewis and Mindich continued their squabble and neither saw the Phoenix as more than a pesky fly. Finally, I gave them an ultimatum -- let me start to create a major newsweekly or I'll quit and go do something else with my life. Continued work in a hostile environment was no longer an option. I gave them two weeks.

My wife at the time, Nicole Symons, found life with me difficult given what I was dealing with at BAD. Was I married to her or to the paper? In an attempt to keep my marriage intact, when two weeks went by and nothing had changed in the Lewis-Mindich feud, I quit as the editor of BAD. I stayed home and started writing a novel. I watched the Cambridge Phoenix basically mirror BAD but with a news front. The Tarter weekly followed a few pages of anti-establishment news with arts reviews and listings. But it was a struggle. Were there really enough advertisers to support two similar publications? Why should I stick around and wait for both of them to collapse? Nicole, known as Nicky or Nicki by most people, and I jumped in the Mustang and decided to see America by way of friends who live elsewhere. After spending a few days with her brother at the University of Miami campus, we opted to sell the '65 Mustang to some mechanics, who probably sold it for more money in Puerto Rico, and got ourselves a Volkswagen camper bus. In short order, we arrived in San Miguel de Allende, in the early days of its trendiness. This mountain town in the center of Mexico was (and still is) home to expatriate artists (mainly from the Left), home to a marvelous art institute and home to Nicky's uncle and aunt, with whom we lived for about two months.

The house was on a hill above the center of town. There was a little studio on the property in which I would sit and write on a daily basis. However, when I passed page 150 and my protagonist was still in the bathroom, where he was on the first page, I decided to stop the novel and write some shorter pieces, like poems. I also noticed that my urge to run a real newsweekly had not vanished. I let Mindich know where he could find me, if he had to. The Lewis-Mindich feud had spilled into the courtroom. They were suing each other. This no doubt must have been good news over at the Phoenix.

One day, a little boy with a burro came up the hill and asked for me in broken English. He said there was a phone call for me from the States. The phone was down the hill at the post office. I followed the boy and the burro back to the post office. Mindich was on the line. He had tracked me down. He was feeling his oats. He felt his victory over Lewis was imminent. And when the smoke cleared, he wanted a Village Voice for Boston with me as its editor. Would I come back and start the wheels going? When did he think he could launch the new publication? He figured by May. The phone call was in March, 1970.

Nicky and I decided to take the slow route back to Boston. We crossed into the States through Nogales, Arizona. There was a border incident that I'll never forget. While we were being cleared for customs, we saw police hacksawing through a ski rack on a station wagon nearby. Turns out that was the latest method of smuggling grass or other drugs. So they were sawing the rack into sausages and pushing the bags of grass out with their fingers. We drove the camper bus into California to visit more friends. Then I read an item about how VW buses are valued in Colorado ski country. Since I grew up in Denver and my parents were living there, Denver became our next stop. Sold the bus in Boulder for more than I paid for it in Miami. Mindich called again. I agreed to return and we flew back to Boston.

Turns out Steve had jumped the gun. The feud was not over but BAD had ceased publishing for a short time. Things were still tied up in litigation, such as the name Boston After Dark. Steve asked me to put a staff together and come up with a manifesto for the new publication. Basically I hired the whole BAD staff and added some newsies, such as Paul Solman, Teddy Gross and Bo Burlingham. I also arranged a mutual relationship with the BU news service, run at the time by Mark Phillips, who has spent the last 30 years covering Europe and Russia for CBS News. If we couldn't call the new venture BAD, what then? I looked at a book about early American journalism and discovered that the first paper in Massachusetts was Publick Occurrences. It was banned by the crown almost immediately. Sounded like a good anti-establishment pedigree to me. Steve agreed. The paper went into operation in April, 1970, and by May 4th, we had a reporter at the Kent State shootings. Publick Occurrences was now in competition with the Cambridge Phoenix.

By the end of that summer, Mindich had bested Lewis in court. Lewis went back to Ohio, and Publick Occurrences switched its name back to Boston After Dark. It remained that way until the summer of 1972, when after a series of backers, publishers and financial infusions, the Phoenix gave up the ghost and sold itself to Mindich. In the deal, he got the Phoenix name, some advertisers and the subscription-circulation list. He also took sports writer George Kimball. He already had a staff so why would he take the Phoenix staff? In a state of shock but also in a state of determination, the staff of the Phoenix with a small amount of investment money rebounded and put out its own paper, The Real Paper, which lasted until 1981. The Boston Phoenix, formerly BAD, is still with us. And I'm still fretting over not having that piece of profit -- which, by the way, was never offered. After all, I had editorial control.