The Doctor at Park Avenue Armory

Is it Possible to Function in Fully Human Mode

By: Viktor Raykin - Jun 16, 2023

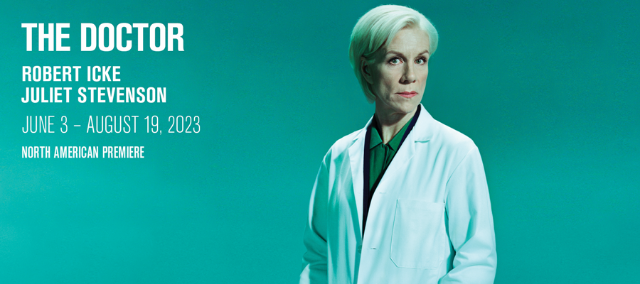

Arthur `Schnitzler's play Professor Bernhardi has been completely rewritten by director Robert Icke, who takes the action from 1900 Vienna to present-day Britain. Now called The Doctor, it was a smash hit in London and is running until August 19th at the Park Avenue Armory in New York.

Schnitzler (1862 - 1931) was a Viennese doctor who became a writer and playwright (his fate makes us think of Chekhov and Bulgakov). He wrote the play Professor Bernhardi in 1912, at a time when the social and political atmosphere in Vienna (then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) was tense and polarized, dominated by extreme right-wing and extreme left-wing forces. Liberalism was in decline, and anti-Semitism on the rise.

The unknown Adolf Hitler sought sustenance in the streets of Vienna as a "free artist." Vladimir Lenin lived in exile in Paris. Two years later, the world war would lead to revolutions and the collapse of the great empires.

Yet, in Professor Bernhardi, there are no loud politics, wars, or regime collapses. It is about the state of the minds of intellectuals and the internal politicization in which the state of all society is expressed. "Identity politics" is a modern term (inhuman in concept), not yet present in Schnitzler's time. The play is precisely about what it is like for a person crucified at the coordinates of this "politics."

A 14-year-old patient dies in a clinic - a botched abortion, followed by sepsis. The head doctor, Ruth Wolff brilliantly played by Juliet Stevenson, knows that death is inevitable, but does not tell the girl and does not let the Catholic priest perform the "last rites." Her duty as a doctor is to abide by patients’ directives. Absent a preference, the patient should die in peace.

Dr. Ruth Wolff founded the clinic and is Jewish. She "despises" the right of Catholics to perform their religious rites.

The fight between priest and doctor is instantly leaked to social networks and the press, and a petition is drafted with thousands of signatures. It turns out that half of the doctors at the clinic are Jewish. And they are white. And most of the employees are men.

The harassment escalates to the point where Ruth refuses to accept the position of chief doctor, but wants to continue her research at the clinic, which she is also denied. At the same time, she does not back down one iota from her position: her decision was purely medical and correct. Not allowing a priest to visit the dying woman, she acted in the interests of the patient. She has no religious or racial prejudices.

The conflict reaches its climax when Ruth participates in a televised debate, more properly called a tribunal. She sits in front of a line of prosecutors, each of whom has a different point (or rather, "point") of accusation. One asserts that she despises Christians, another that she is "racist"; a third that she encourages abortion; a fourth that she is a misogynist. The painful facts of her personal life are brought to light. The doctor is smeared with verbal tar. She is virtually lynched. All that remains is to accuse her of drinking the blood of Christian babies and calling her a "poison doctor".

Ruth fights back as best she can. She sits with her back to the audience and we see her face close-up on the big screen. For a moment, it seems as if she is finished. Indeed, at home, left alone, she spells out the idea of suicide. She has reached the end of the line. From the proud, confident professional we saw in the beginning, she has turned into a small, hunched, gray person. Her white coat was torn off her. She has been turned away. She doesn't believe in herself.

Then that same priest comes to her, and they have an important conversation. He says that she did the right thing, that if he were her, he too would have let the girl die in peace and in ignorance. During the bullying, he couldn't stand up for Ruth, because he did not want to compromise the church. "I acted like a priest, not 'just' a person," he says. The church is bigger and more important than 'just' a person. You have to have humility, and then everything falls into place.

A huge inner drama is going on in front of our eyes. This soulful work is played so truthfully by Juliet Stevenson that the audience forgets they are in the theater. Ruth Wolff, deceived, scorned, humiliated, seeks and finds the strength to raise her head and speak those words with new meaning and new dignity: "I AM A DOCTOR."

The play is over. Yet questions are left in its wake. Is man reduced to any identity (even if it is the one he has chosen for himself)...? Is there room in modern Western society for "just" a person? Could the heroine say of herself, "I am Ruth Wolff. I am a human being..." - and only after that, "I'm a doctor?"