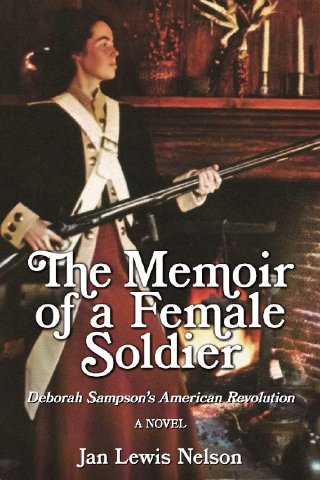

Jan Lewis Nelson's Book on Deborah Sampson

Disguised as a Man She Fought in the American Revolution

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 06, 2023

The Memoir of a Female Soldier: Deborah Sampson’s American Revolution

By Jan Lewis Nelson

With foreword by Steve Nelson

Massaemett Media

Copyright 1977, published 2023

403 Pages

Available through Amazon

The trope of the historical novel by Jan Lewis Nelson is that she is relating a tale to us as “patient reader” about the 17 months when Deborah Sampson served during the American Revolution.

It is as though the long lost manuscript has at last been discovered.

“And so before I conceal my manuscript and take the solemn pledge to my family to keep it well hidden until after the death of my husband and myself, I affix my signature and thus with a full heart do swear myself,

“Your most respectful and obedient servant.

“Deborah Sampson Gannett

“4th Massachusetts Regiment, Light Infantry, Aide to General John Paterson; Wounded in combat and Honorably Discharged from the Continental Army of These United States by General Henry Knox, Commander at West Point upon Hudson’s River, October 25, 1783.”

There is a bit of legerdemain between fact and fiction. While the author alluded to Sampson’s subsequently lost manuscript that proved to be true of her own work. Perhaps inspired by the Bicentennial, after three years of intensive research, the copyright of the book is 1977. It languished until the present.

It has now been published by her husband Steve Nelson. As he explained to me, “Not long before Jan died, I told her I would help her publish her previously-unpublished book about Deborah Sampson, the product of three years of research and writing. But first she wanted to reread it and perhaps edit or rewrite parts of the manuscript. Unfortunately she passed away before being able to do so. After her death I was left with two choices: to discard her work, or to publish it in its current form. For me to do any substantive editing, which would require my doing rewriting in her voice, was out of the question.”

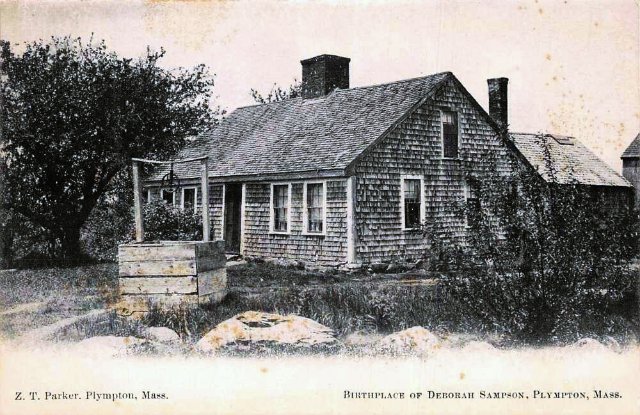

The research on Sampson played a role in their relationship and marriage. For several years they had been living in sin. She met Charles H. Bicknell a local historian in Plympton, Mass. He knew a lot about Sampson and helped in her research. By serendipity the Sampson homestead required a house sitter just after its elderly owner passed on. To seal the deal they were married on site with just their immediate families.

They were both much in ‘Founding Father” mode. Steve wore his pony tail with a ribbon and they posed for pictures in period garb. Steve was marketing a Bicentennial project which he dubbed “Thirteen Stars.”

Deborah Sampson (Born December 17, 1760- Died April 19, 1827 of yellow fever) may have been the first woman to take a bullet (actually two and a saber swipe to her head) in service to our nation.

The army was so desperate for recruits that it was oblivious to gender. There were no physical exams required for enlisting.

So little is known of women who served in this period, that even this single, stunning fact may be in dispute. Research suggests that there may have been several hundred women warriors. The army was so desperate for recruits that it turned a blind eye.

Sampson is known to us because she was honorably discharged and publicly petitioned for back pay, pension, and then for status as a disabled veteran. She was backed in this process by her good friend Paul Revere and officers under whom she served with distinction.

While born of good Yankee stock her family was poor. A philandering father abandoned them and Deborah was placed first with relatives and then indentured. She learned basic skills in spinning and, while denied education, on her own became literate. That was rare for her lowly social class and unheard of for an independent woman.

The bounty for enlisting, which she tried twice, was a likely inducement as well as the regular pay and board as a soldier. That proved to be as flimsy as winter at Valley Forge.

She was mustered in Worcester, where she signed the receipt for the £60 enlistment bounty as “Robert Shurtlieff” (the receipt was discovered by Jan in an archive in Massachusetts).

Poverty was an issue after the war as it was for all Americans in the new and under-funded Republic.

Sampson married Benjamin Gannett (1757–1837), a Sharon, Massachusetts farmer, in Stoughton, Massachusetts on April 7, 1785. They were the parents of four children: Earl (b. 1786), Mary (b. 1788), Patience (b. 1790), and Susanna Baker Shepherd, whom they adopted after she was orphaned. They lived with Gannett's father on the Gannett family farm, but had limited success because it was smaller than average and the land had been overworked.

To make money she told her story to Hermann Mann who published The Female Review: Life of Deborah Sampson: The Female Soldier in the War of Revolution. To boost sales he played loose with the facts. Lewis Nelson expresses Sampson’s anguish over fabrications. She saw action but did not fight in the Battle of Yorktown as Mann falsely claimed.

The book sold modestly but failed to lift the Gannett family out of debt. There was discussion of a second edition which Sampson, according to Lewis Nelson, hoped to revise. There is reference to a memoir which might be published by Paul Revere. Her alleged intent was to set the record straight and make some money.

Mann had another moneymaking plan. He would produce her on stage and manage a tour. That partly happened as she appeared on stage in Boston in 1802. For a year she toured widely in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and upstate New York with but a single performance in New York City. On opening night she was panned by a critic. After expenses there was little or no profit.

But Sampson proves to have been the first American woman to go on a speaking tour. The act comprised a speech about her service, then, a costume change into her Continental uniform, when she executed the impressive manual of arms.

The book is best approached less for history than as a work of literature. There is a trope of parallel narratives delivered in the patois of the period. From present time each chapter begins in italics. The author is discursive with a fluid overview of the métier of the moment. Here the literary imagination is stoked to create a vivid canvas of rural New England during an era of war. It is an intimate and feminine view with emphasis on the simple and quotidian struggle for survival.

The italics passages float freely and then give way to the straightforward daily grind of private Robert Shurtlieff. There is the constant tension of maintaining the masquerade of gender. Here the pace of reading quickens as we are absorbed by compelling and at times precarious details.

The artificial tone of her novel evokes the intimate style of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. That 1749 publication is regarded as the first novel. Lewis Nelson fabricates the vernacular of the period as well as Fielding’s device of chatty asides to the reader. This also results in frequent recaps attempting to keep “dear reader” on track while advancing the plot. These devices appear in the italics passages and make us all the more eager for the straight talk of army adventures.

We learn what it means for a woman to bunk with a rough band of soldiers. We get but glimpses of negotiating latrines and rare instances of bathing. Her physical proportions and general conditioning were assets. She was inches taller than most with homely, boyish figure and features. She bound her small breasts.

By all accounts she was a decent soldier and qualified for the elite light infantry. She stood her ground and there is reference to running through an enemy with her bayonet; after which, she went off and vomited.

There are hints of her sexuality. She was expected to join her comrades when they went wenching. More than a few tarts and even polite young ladies hit on her. The author down plays this much to her credit.

Mostly what comes through in this novel is the utter squalor of army life. Starvation and disease were as much to be feared as the enemy. Conditions at West Point are well researched and conveyed.

When she was injured she snuck away from medical treatment out of fear of discovery. She dug out one musket ball but the other was too deep. Reporting back for duty in April, 1783, she was assigned as an aide to General John Paterson.

He was one of Washington’s inner circle of trusted officers. Prior to the war he had been a lawyer in Lenox, Massachusetts, a member of the town Select Board and the town’s representative to the colonial legislature. The obelisk in the center of the Lenox round-about is dedicated to Paterson.

That promotion came with a horse which was most helpful when they marched from West Point to Philadelphia.

Mutinous soldiers surrounded Congress demanding their pay. The matter was settled but fever spread. In the sweltering heat of summer, Philadelphia was ravaged by a deadly plague known as “brain fever.” Deborah caught it in September and was nearly given up for dead. But a faint sign of life caused the well-respected Dr. Barnabas Binney to examine his patient, whereupon he discovered the binding on her chest and was surprised by what lay beneath it.

Binney had Deborah removed to his home where she was treated in private, her secret kept. After several weeks of recovery, Binney sent her back to West Point, still in uniform, with a sealed letter to Paterson. It disclosed her true identity, while praising her service in aiding ill soldiers.

It is much to the credit of her commanders that the criminality of her deception was overlooked in appreciation of her service. She might have faced incarceration and even execution. Notably, she was excommunicated from her church after being outed during her first attempt to enlist.

Sampson’s saga has a lot to say about the weaker sex.