Figurative Expressionism in Provincetown

PAAM Exhibition Through September 2

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 21, 2013

Pioneers from Provincetown: The Roots of Figurative Expressionism

Curated by Adam Zucker, Co-curator, Stephanie DeTroy

Provincetown Art Association and Museum

Director, Christine McCarthy

460 Commercial Street

Provincetown, Mass. 02657

July 19-September 2, 2013

Catalogue: 52 pages, Published by the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, ISBN: 0-9852761-3-4

Essays by Adam Zucker, Charles Giuliano and Stephanie DeTroy

Sun Gallery and a Return to the Figure in the 1950s

"When I brought Hofmann up to meet Pollock and see his work which was before we moved here, Hofmann’s reaction was — one of the questions he asked Jackson was, do you work from nature? There were no still lifes around or models around and Jackson’s answer was, 'I am nature.' And Hofmann’s reply was, 'Ah, but if you work by heart, you will repeat yourself.' To which Jackson did not reply at all." (Attributed by Lee Krasner (1964) in "Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1964 Nov. 2-1968 Apr. 11", interview with Dorothy Strickler for the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art.)

During the Post War era through Abstract Expressionism and the New York School American art enjoyed what would prove to be an era of global dominance. By the 1950s younger artists were finding that Pollock and Abstract Expressionism narrowed their options. Among the next generation, in major art centers across America, there was ubiquitous discussion of a “Return to the Figure.”

That dialogue was particularly cogent during summers when artists gathered in Lower Cape Cod. Many came to study with Hofmann. This exhibition “Pioneers of Provincetown” focuses on a vibrant group of artists who comprised the inception of a regional aspect of the movement of Figurative Expressionism.

The traditional view of modernism was an assumption that each generation comprised an avant-garde elite that absorbed the most radical developments of the previous generation and pushed them further.

Depending on where you want to fix the goal posts modern art may, arguably, begin with Giotto and end with Pollock. The history of modernism is often framed as an intellectual conflict between reactionary and progressive forces.

During the 19th century in France it was a struggle between the established artists of the academy L'art pompier and the more radical movement of romanticism which elided into the naturalism of depicting nature and progressive social agendas of impressionism.

During post impressionism Paul Cezanne abandoned liner perspective with multi-valent compositions that evoked the fourth dimension and development of cubism by Pablo Picasso and George Braque. The maximum entropy of modernism resulted in the most extreme forms of abstraction and non objective art. Arguably, abstract art reached its apogee in 1918 with “White on White” (MoMA) by Kazimir Malevich.

There were many inferences of spirituality and deism in a vision quest for the purest and most advanced tropes of modernism. A notable example is the 1911 treatise of Wasilly Kandinsky Über das Geistige in der Kunst.

That notion of an uber Apollonian, one true and pure art, informed the theory and criticism of Abstract Expressionism espoused by Clement Greenberg. It was sustained by a cult of post modern critics based on philosophy and poetry that largely formed an end around the studio practice and dialogue of artists. The critic trumped the artist as arbiter of meaning and value.

The post World War II cultural dialectics were particularly aggressive, elitist, class conscious, leftist and xenophobic. During the purges of Stalin the American left was in disarray and under attack from McCarthyism.

In the fine arts one of the casualties of dynamic change was the critical dismissal and denunciation of the idealist, leftist Social Realism which prevailed during the hard times of the Depression of the 1930s. During the Cold War of the 1950s the agit-prop agenda of aspects of lingering narrative figuration was regarded as knee jerk, unsophisticated jingoism. With the progressive stages of development toward abstraction, culminating in the Post War New York School, all aspects of representation and figuration were considered as collateral damage.

With Europe recovering from the devastation of war there was a paradigm shift from Paris to New York as the locus of advanced art. Harold Rosenberg championed “American Type Painting” and “Coonskinism.” Irving Sandler chronicled The Triumph of American Art. (I asked Sandler if Triumph implied a victory for the American avant-garde? He responded that the title was a decision of the publisher to help sell the book.) In 1985, Serge Guilbaut wrote a controversial, much debated book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.

Virginia Woolf contributed to the class and culture wars in 1942 taking a position defining a new term middlebrows as petty purveyors of highbrow cultures for their own shallow benefit. Quoting her and other highbrow proponents, such as art critic Clement Greenberg, Russell Lynes parodied the highbrow's pompous superiority.

If, for Greenberg, the formalism and abstract artists he favored as the best and most progressive, were as Lynes observed, Highbrow, then, by definition those he scorned, the exponents of Social Realism, the American Scene, and Regionalism were Middlebrow or even Lowbrow.

Approaching a gallery of work by Boston Expressionist, Jack Levine, and Social Realist, Ben Shahn, Hilton Kramer, the art critic for the New York Times, wrote that he could “smell the pastrami.” At Skowhegan I asked him about the quote which he confirmed but did not apologize for. “It was just a matter of one Jew criticizing other Jews” he told me.

The message for ambitious artists was to set the social and intellectual bar as high as possible. Today, there are as many styles and forms of art as there are artists. It is difficult to understand the Post War era in American culture when the critical discourse was so polemical. As high priest and taste maker, Greenberg was didactic in defining the best artists and why. One litmus test was their purity in pursuit of radical abstraction. In his assessment, for example, Pollock was more important than deKooning because of the latter artist’s reactionary fixation on the Woman theme and figuration which ran parallel to abstraction in his oeuvre.

Pollock’s comment “I am nature” may be regarded as the inception of post modernism. It implied an egocentric shamanism that obviated the need to refer outside his psyche as a source for the work. Instead of looking out at the world, as Hofmann suggested, he looked ever deeper into himself. It resulted in the most unique and acclaimed oeuvre of his generation.

Subsequent artists from formalism through minimalism operated by rules and a vocabulary which no longer was “abstracted” from nature. A turning point and exit from “abstracted art” was Helen Frankenthaler’s 1952 “Mountains and Sea.”

The Highbrow rejection of working from observation represented a tipping point for artists to work back from abstraction to rediscover nature as a source for advanced, experimental work. Other options were to continue the influence of the New York School into a Second and Third Generation of Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, and beyond into what Kenworth Moffett dubbed New New Painters (1978).

By the mid 1950s many young artists, with funding through the GI Bill, traveled to Provincetown to study with Hofmann and the more conservative Henry Hensche. In Provincetown’s studios, bars, and social gatherings an emerging generation of artists anticipated a “return to the figure.” It was mostly a matter of when and what form it would take.

Provincetown in the 1950s was a fertile matrix for critical thinking. The most radical activity focused on the Sun Gallery of Yvonne Andersen, an artist, and her late husband, Dominic Falcone, a poet and visionary. They worked odd jobs to support the gallery which took just 20% from the occasional sale.

They took over the space of the artist and jewelry maker Earle Montrose Pilgrim who also was first to show several of the later Sun Gallery artists, Lester Johnson and Wolf Kahn, who eventually numbered 100. There were weekly exhibitions including solo, two and three man as well as group shows. Falcone organized readings. Andersen, an artist, became interested in animated films, which were shown in the gallery, and shot footage of openings with a 16 MM Bolex. The first Happening with artists as performers was staged at Sun Gallery by Red Grooms, his then girl friend Sylvia Small, Andersen, Falcone and the artist Bill Barrell. (He ran Sun Gallery after Andersen and Falcone left Provincetown) .

There was a strong connection between Provincetown and the artist run Hansa Gallery, 1952-1959. 70 East 12th Street - Fall 1952 - Fall 1954. 210 Central Park South, Fall 1954 - Summer 1959. (* denotes original members). Edward Avedisian, Maurice Barr, *Jacques Beckwith, Robert Beauchamp, Lilly Brody, *Jean Follett, * Barbara Forst, *Miles Forst, Hedi Fuchs, Paul Georges, *John Gruen, Dan Haugard, *Wolf Kahn, *Allan Kaprow, Fay Lansner, Andrew Martin, Dody Muller, *Jan Müller, *Felix Pasillis, George Segal, * Arnold Singer, * Richard Stankiewicz, Myron Stout, Robert Whitman, *Jane Wilson. Directors of the Hansa Gallery were Richard Bellamy and Ivan Karp.

The debates of New York continued in Provincetown. An artist, poet and jazz critic, Weldon Kees, as well as Provincetown artist Karl Knaths and others, organized the summer long Forum ’49. A return to the figure was not a part of its agenda.

The current exhibition focuses on artists who pursued aspects of figuration in the 1950s. They are a part of the yet to be adequately defined and researched movement of Figurative Expressionism.

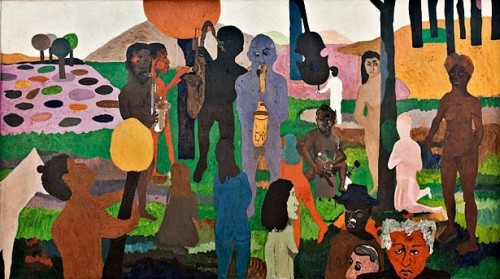

There are works on view by Yvonne Andersen (Born 1932), Bill Barrell (Born London, 1932), Robert Beauchamp (1923 –1995), Gandy Brodie (1925-1975), Emilio Cruz (1938-2004), Red Grooms (born Charles Rogers Grooms on June 7, 1937), Mimi Gross (Born 1940), Wolf Kahn (Born in Stuttgart, Germany, 1927), Lester Johnson (1919 – 2010), George McNeil (1908-1995), Jay Milder (Born 1934), Jan Muller (December 27, 1922 – January 29, 1958), Peter Passuntino (Born 1936), Earle Montrose Pilgrim (1923-1976), George Segal (1924-2000), Bob Thompson (1937-1966), Selina Trieff (Born 1934), and Tony Vevers (1926-2008).

The list was derived by the curator Adam Zucker, a Ph.D. candidate researching the Figurative Expressionist movement. Some of the artists were a surprise to me and I have also suggested artists as well as resources for key works.

The exhibition and this essay have been opportunities to come back to themes and issues that I explored but set aside.

The David Anderson Gallery (son of Martha Jackson who died in 1969) commissioned me to research and publish a catalogue essay for the traveling exhibition organized by the Westmoreland Museum of Art in Greensburg, Pennsylvania; Lester Johnson selected paintings, 1970-1986 editor and curator, Paul A. Chew; essays, Harry Rand, Charles Giuliano.

During sessions with Johnson there was considerable discussion of his early years in Provincetown. He was one of the few figurative members of the seminal Artists’ Club in New York. We discussed other figurative artists particularly Jan Muller, Red Grooms and Bob Thompson who he recruited to the Martha Jackson Gallery.

Working with Karl Hecker of the David Anderson Gallery I curated the exhibition Kind of Blue, 1986, for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. The four man show- Benny Andrews, Emilo Cruz, Earle Montrose Pilgrim and Bob Thompson- traveled to the Gallery of Northeastern University. The title based on a seminal album by Miles Davis reflected the fact that the artists were African American. Hecker loaned a major work by Thompson and introduced me to his friend Cruz. His painting, which was used for the exhibition poster, was acquired for the museum of the Rhode Island School of Design.

It is interesting that they are now viewed as figurative expressionists and are included in the current exhibition. With the exception of Andrews for reasons that escape me. Perhaps because Benny continued aspects of Social Realism which, as we have noted, was anathema. One can see in his work connections to Robert Gwathmey, Horace Pippin, Jacob Lawrence and Philip Evergood.

Thompson, one of the most interesting of the Provincetown artists of his era, drew influence from Piero Della Francesca and Italian Renaissance painting with a dash of Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry.

Before becoming involved with the current project my notions of Figurative Expressionism were rooted in the work of Johnson, Thompson, and Muller. Recent research which is reenergized and ongoing is broader and deeper. There is much work yet to be done with the Sun Gallery artists as well as other groups of figurative expressionists.

To date nobody has connected the dots of parallel developments in San Francisco in the work of Bay Area Figurative Artists David Park (1911-1960), Richard Diebenkorn (1922 -1993), Nathan Oliveira (Born 1928) and Joan Brown (1938-1990). Or the early work of Leon Golub (1922-2004) in Chicago.

During the 1960s the Warde Nasse Gallery had a compelling exhibition from the estate of Stanley Pransky who died young a suicide. There is work yet to be done in an evaluation of the generation of Post War artists who were influenced by the Boston Expressionists; Hyman Bloom (1913-2009), Jack Levine (1915-2010) and Karl Zerbe (1903-1972). If a return to the figure was a mantra for advanced art during the 1950s, in Boston which ignored Abstract Expressionism, it never went away.

Zucker is researching figuration among New York artists who are not included in this exhibition. As research continues more artists will be considered in the critical dialogue.

The phenomenon of the “Return to the Figure” and Figurative Expressionism is obfuscated by misunderstanding and misinformation. It is too generously applied as a one size fits all movement.

Much of the confusion resulted from the Peter Selz exhibition “New Images of Man” for the Museum of Modern Art in 1959. Selz conflated European and American artists. Prominent Europeans included Francis Bacon, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti and Cesar. The established Americans featured Pollock and deKooning. Among the Figurative Expressionists he chose Muller (by then deceased), Diebenkorn, Golub, and Nathan Oliviera. Red herrings included Leonard Baskin, Balcomb Greene, Rico Lebrun, Germaine Richier, Theodore Roszak, and Fritz Wotruba. An eccentric choice was H. C. Westermann.

There was indeed a return to the figure but not in the way that many artists had anticipated. The MoMA show missed the mark in exploring a return to the figure among American artists. Selz was out of touch with the dialogue among artists. Of the Provincetown artists only Muller was included. When I first saw and wrote about work by Bob Thompson at Martha Jackson Gallery he was deceased.

What is interesting about the Sun Gallery period (1955-1959) was its sense of youth, commitment and experimentation. A number of the artists began to have exposure in New York. It was logical to assume that they would comprise the next major movement after Abstract Expressionism.

That was derailed by the emergence of Pop Art and its global dominance. Some of the transitional artists- Red Grooms, George Segal, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Rivers- are now included in the discourse of Pop with scant attention to their roots in Figurative Expressionism.

Some of the alumni of the Sun Gallery group and new colleagues regrouped as Rhino Horn a movement that is known only to a handful of artists and scholars. (Rhino Horn: Jay Milder, Peter Passuntino, Bill Barrell, Ken Bowman (Born 1937), Michael Fauerbach (1942-2011), Peter Dean (1939-1993), Benny Andrews (1930-2006), Nicholas Sperakism (Born 1943), Leonel Gongora (1932-1999).)

The primary motive of this exhibition is to bring together a dynamic group of artists who were experimenting with ways to address figuration in a fresh and relevant manner. Having absorbed the lessons of Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg and Hofmann there was no element of the earlier movements defined by Patricia Hills and Roberta K. Tarbell in the 1980 exhibition “The Figurative Tradition: Whitney Museum of American Art.” Of the Provincetown artists only Muller and Thompson were included.

Hills identifies Muller as a Hoffman student “…his works recall the intensity of Fauvism and German Expressionism. Sandler situates Muller’s place as an expressionist abstract painter within the New York School.” On Thompson Hills states “…the Fauve -like fantasy landscapes of Bob Thompson such as An Allegory of 1964. Like Jan Muller whom he admired, Thompson in his decorative scenes sought to express a private vision of search and salvation.” There is no mention of Sun Gallery, Figurative Expressionism, or the Rhino Horn group.

While a number of the artists in this exhibition studied with Hofmann they also broke from his didactic influences. They either opted to work independently or study with Hensche.

What remains to be sorted out, perhaps starting here, is how this loose confederation of like minded artists evolved through exhibitions, happenings, social events, debates, and studio visits during intense summers on Cape Cod.

It is insightful to see the flat, linear, poetic figuration of Vevers compared to similar elements in works by Thompson. All accounts of artists of this group discuss the importance and influence of Muller. The exhibition includes two versions of works related to his funeral by Vevers and Thompson.

Many will be surprised to see early paintings by George Segal in this exhibition. He is better known for the later plaster casts and groups of figures. I would have liked to see some of the early works of Claes Oldenburg in Provincetown or the eccentric work that Alan Kaprow showed at Sun Gallery.

As a major movement of post war American Art, Figurative Expressionism has attracted scant attention among established critics, curators and art historians. Hopefully, this exhibition, its related programming and critical dialogues, will stimulate interest in further research and future exhibitions.

We have yet to see a major museum take on the project of a national overview of the return to the figure in the 1950s. It would be ambitious to connect the dots of simultaneous developments in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, and Provincetown.

For most visitors to the exhibition many of the individual artists seen in this context will be fresh and informative. Perhaps it will evoke Honoré de Balzac’s Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu. Then at night to sleep and perchance to dream.

This essay was written for the exhibition catalogue.