Satchmo at the Waldorf at Shakespeare & Company

John Douglas Thompson Solos in Terry Teachout Play

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 25, 2012

Satchmo at the Waldorf

By Terry Teachout

Directed by Gordon Edelstein

John Douglas Thompson as Louis Armstrong, Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis

Set Designer, Lee Savage; Costume Designer, Ilona Somogyi; Lighting Designer Matthew Adelson; Sound Designer, John Gromada; Stage Managers Diane Healy and Hope Rose Kelly

Tina Packer Playhouse

Shakespeare & Company

Lenox, Mass

August 22- September 16, 2012

Production Supported by Sol Schwartz for Elayne

Long Wharf Theatre

New Haven, Connecticut

October 3 to November 4, 2012

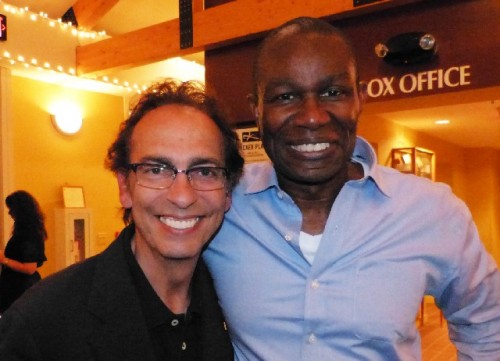

John Douglas Thompson has been described by the New York Times as “One of the most compelling classical stage actors of his generation.” With a stunning performance at Shakespeare & Company of Satchmo at the Waldorf, a new play by Wall Street Journal theatre critic, Terry Teachout, Thompson has set the bar even higher.

Over the past several seasons Thompson has developed a solid fan base in the Berkshires for his leading roles in Othello and Richard III. He also performed in The Dreamer Examines His Pillow by John Patrick Shanley. While his primary focus has been on roles in Shakespeare (Antony and Cleopatra, Macbeth, King Lear), in Hartford and New York, he has also appeared in plays by Eugene O’Neill, The Emperor Jones and The Iceman Cometh. We have discussed his roles as Rufus Jones and Joe Mott in the O’Neill canon.

Those who have followed his career have long anticipated a breakout. Satchmo which has been uniquely crafted to his remarkable skills, moves to Long Wharf Theatre where it will be honed for a potential New York run on or off Broadway. Based on a cameo in the recently released Bourne Legacy we also expect to see more of him in film and TV.

For now, act fast and don’t miss this sensational new play which ends all too soon on September 16. Once the reviews come out tickets will likely be hard to come by. It is not everyday that we experience a work of genius combining an actor who is fast becoming a national treasure and, remarkably, a first play and out of the park, bases loaded, home run by the versatile and uniquely gifted Teachout.

This past winter I read Teachout's “Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong.” It inspired me to digitally transfer many Armstrong LPs to the hard drive and CDs. That led to broader research into the formative years of New Orleans jazz exploring the white pioneers, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (the first to record jazz and an inspiration for Armstrong), Bix Beiderbecke whom Armstrong admired and jammed with, trombone player and long time Armstrong associate, Jack Teagarden. I also listened intently to the Creole musicians pianist Jelly Roll Morton and soprano sax player Sidney Bechet. Other trumpet players including Bunk Johnson, Freddie Keppard, Tommy Ladnier, Papa Celestin and clarinet players Johnny Dodds, Alphonse Picou and George Lewis. As well as Armstrong’s recordings with the Hot Five, Hot Seven, King Oliver, Luis Russell, and Earl Hines. Many of these CDs I shared with Thompson and several jazz fans. It was a kind of intensive winter seminar on early jazz.

Little of which, however, informs the Teachout play. We hear the music in the background and in one stunning scene Armstrong breaks down the classic “West End Blues” demonstrating how he brilliantly front ended the run up to High C before dropping down into the tune. Armstrong was noted for hitting High C dozens of times in performances eventually causing him to split his lip and mess up his chops while touring in England.

In the play Armstrong's trumpet is little more than a prop. After the gig he breaks down and cleans the horn putting it to rest for the night.

There is an interesting mantra in which he states that he stays where he plays. Hence the Waldorf in New York. He informs us that he "intergrated" many of the nation's top hotels by performing in their nightclubs and ball rooms.

During the Roaring Twenties, when Armstrong made it up river from the Crescent City to Chicago, the clubs were run by Al Capone’s mob. When he sought better opportunities in New York the gangsters also controlled the nightclubs. The famous Cotton Club in Harlem featured black entertainers and high yellow dancers but was off limits to blacks. Satchmo found himself stuck in the middle between rival mob elements attempting to exploit his best selling records and growing popularity.

In a jam he reached out to Joe Glaser, the son of a doctor, and Jewish gangster who ran clubs and cat houses for Capone in Chicago. The fillies were an Achilles heel for Glaser. This emerges as a central theme in the play. Glaser sampled the goods and got nailed by the heat for hammering jail bait. The mob covered it up but held a marker on him that eventually screwed Satchmo.

With Armstrong as his primary client Glaser managed many top black entertainers. The business was worth millions when he was forced to take on the mob as a partner. When he died Armstrong was screwed out of a share in the business he helped to build. We hear Amstrong cursing the man he regarded as a friend and brother.

While Teachout, a former jazz bass player, knows the music inside out, the book is a page turner and must read, he put on another hat to create an evening of compelling theatre. Teachout is currently working on “Mood Indigo: A Life of Duke Ellington.” Perhaps it will follow a similar evolution from music bio to play.

For Satchmo at the Waldorf Teachout has focused on the last months of his life when mortally ill with congestive heart disease. Thompson, who is 48, aptly conveys an old, sick man (born, so he claimed, July 4, 1900, actually August 4, 1901) who died at 70. At the Newport Jazz Festival I covered his 70th birthday celebration.

The Armstrong of the late years was mostly known for that bug eyed, smiling, laughing, handkerchief waving, clowning around, entertaining persona. Glaser told him that he didn’t even need to play the horn. The days of High C’s were long gone. Glaser hired and fired band members and told Armstrong what to record. One of those songs, a 1963 demo before Hello Dolly opened with Carol Channing in 1964, became a number one hit. It knocked the Beatles off the top of the charts and won him a Grammy in 1965.

While Armstrong, AKA, Pops, Dippermouth, Dip’mo, Satchel Mouth, or Satchmo, was the first jazz superstar and one of music’s most influential artists, the play focuses on the very human aspect of the love/ hate, bond and conflict between the musician and his manager. It highlights Glaser’s ruthless betrayal.

A courageous, risky trope of this play has Thompson playing both characters. This is achieved seamlessly. We find Louis in his Waldorf dressing room after the gig. He enters silently taking a wiff from an oxygen tank to catch his breath. There are the famous reel to reel tape recorders which have left a remarkable legacy that Teachout drew upon. He also traveled with a portable typewriter and dashed off numerous ten page letters. The back wall of the thrust set, designed by Lee Savage, features a dressing room and mirrors surrounded by lights. This occasionally dissolved into a view of Manhattan from an office window. This simple device triggered the presence of Glaser.

We also encountered a physical shift from the slouched, stooped posture and voice of Armstrong to the erect, strident, and different demeanor of Glaser.

The language of both men is so harsh, foul mouthed and laced with racial epithets that initially the audience gasps with self conscious laughter. Some of the lines, as directed by Gordon Edelstein, are played for humor. But this is hardly a comedy. It is an unsettling and deeply disturbing story of the uneasy and complex alliance between an iconic, black, jazz master, and his ersatz friend and protector, a Jewish mobster.

Armstrong shows us the Star of David that he wears. We learn that as a child, the son of a Storyville prostitute, he was protected and fed by the Jewish Karnovsky family. He tells us, ironically, that Jews had always been good to him.

A man of little or no formal education, he learned cornet playing in the band of the Colored Waifs Home. He had been arrested as a juvenile for firing a gun on the street.

Glaser took care of him and kept him on the road, when possible in first class hotels, some 300 nights a year. Only rarely did he get to spend time in Queens with his fourth wife, Lucille. Louis just wanted to make music and had little regard for money. Glaser paid the bills and gave him cash when he needed it. He tells us that Satch was a soft touch who gave away as much as $1,000 a week to thousands of folks over the years.

For aficionados and fellow musicians, for the last 25 years of his career under Glaser's management, Armstrong was a shucking and jiving Uncle Tom. He did indeed make some disgraceful recordings including a late Country Music album. I listened to it as part of my research. Much of the late work pales by comparison to his first recordings with King Oliver or the seminal Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings of the 1920s. When the big band era ended after WWII, his career was reinvented as Louis Armstrong and His All Stars. Under Glaser’s control those bands varied greatly in quality. He made memorable recordings with Ella Fitzgerald, Porgy and Bess, and Duke Ellington. The first jazz album I acquired as a teenager was Louis Armstrong Plays the Music of W.C. Handy with singer Velma Middleton. It is still among my all time favorites. Other enduring albums are Ambassador Satch and Satch Plays Fats.

Armstrong was deeply hurt by comments from bop players Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. They were advocating a more sophisticated, progressive music. Satch was a flashpoint in the divisive debate between advocates of trad, or Dixieland revival, Hot vs. the Cool School of Bop. Significantly, Armstrong performed for all white audiences. Ironically, eventually, that was also true for Dizzy and Miles.

Orval Eugene Faubus (January 7, 1910 – December 14, 1994) was the 36th Governor of Arkansas, serving from 1955 to 1967. In 1957 he famously defied a Supreme Court decision to integrate schools. President Dwight D. Eisenhower initially declined to enforce the law with federal troops.

Armstrong, an alleged Uncle Tom, was incensed. A cub reporter bribed a waiter to allow him to deliver room service to Satchmo. He was granted a remarkable interview denouncing Faubus and Ike. It made headlines all across America. The incident is a highpoint of the play.

While in rehearsal the character of Miles Davis was added. For this transition, with Davis ridiculing Armstrong, the lighting device is a narrow spot. There is a vocal change to a soft voice. Sorry, it just didn’t feel like Miles with whom I spoke on a number of occasions. He had a raspy, hoarse whisper and a distinctly disdainful demeanor punctuated with “Sheeeeeetmuttthahfuggah.” It always warmed my heart to hear him say that. Thompson’s Davis is way too low key and polite. Miles had attitude up the wazzoo.

Most folks who attend this play, if they are old enough to remember Satchmo, or knew him from “Hello Dolly” or High Society with Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly and Frank Sinatra will be shocked and surprised by this bitching and cussing view of him. It is the Louis we never knew.

Teachout and Thompson have pulled back the curtain to reveal an intimate, grippingly fierce and brutally honest, long deep look into the heart and soul of one of America’s greatest artists. It’s a play you will want to see more than once.

Hey MoFo don’t MoFo miss this one. It's off the hook man.