Vietnam Part One

Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon)

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 08, 2010

Though I had been in Viet Nam five years earlier traveling north to south, I looked forward to having a second opportunity in Ho Chi Minh City (the former Saigon), a bustling international port with a population of eight million people, as well as to seeing areas of the Mekong Delta new to me. I was not disappointed.

To get to Ho Chi Minh City, we flew Vietnam Airways from Vientiane, Laos to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, as there was no direct flight to our destination. The first leg of the trip took one hour and twenty minutes; the second was only thirty minutes, following a short wait in the transfer lounge.

Ho Chi Minh is a busy sprawling city that is hot and steamy year-round. The constant stream of motorbikes offers a spectacle of people in conical hats, caps, helmets and scarves; high school girls in white ao dais; and women in long gloves and fashionable face covers for sun protection. Half of the one million Chinese in Viet Nam live in Saigon, as the city is still called by locals. “Saigon” means “land of the gon tree.” Vietnamese, like Chinese, is made up of single-syllable units of meaning. “Nam” means “south”; “Viet Nam” refers to people of the Viet ethnic group living to the south of China. The government used to forbid putting only English names on stores; signs appeared in large Vietnamese words, followed on a second line by English translations much smaller in size. Still, western companies seemed to have made major inroads.

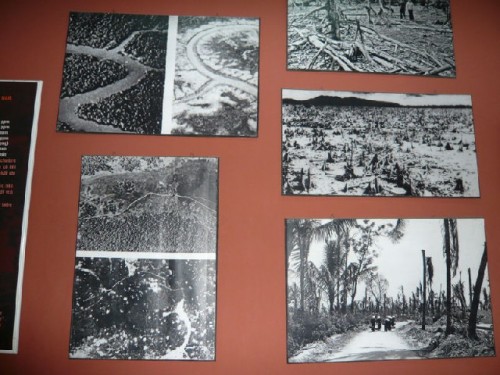

Our city tour began with the War Remnants Museum. Compared to five years ago, it now seemed more crowded with visitors. Remnants of assorted bombs and planes used by the Americans are displayed on the museum grounds; local visitors enjoy posing for souvenir photos in front of these pieces. The indoor displays are of photographs and journals depicting both warring sides. Factual information recalls that three million Vietnamese were killed, four million others were injured and over 58,000 American soldiers died in the war. By the time I got through the museum, I had a big lump in my throat and knots in my stomach, just as I had had after my first visit.

A visit to the market was an incredible sensory experience; women vendors surrounded by bags of goods sipped tea to keep cool and fanned themselves in tiny stalls. Aromas of sweets, dried papaya strings and coconut mixed with those of dried fish. Mounds of mangos, jackfruit, rambutan and durian vied for our attention as shoppers tried to make their way through the narrow lanes, which were also stacked with household goods and clothing. Manicure and pedicure business was brisk.

The majestic Post Office, the Notre Dame Cathedral and the Opera House are legacies of the French Colonial period, along with other buildings lining Saigon’s wide boulevards. New hotels, such as the Novotel, Sheraton and Hyatt, dot the skyline. Jewelry stores and boutiques glitter into the night. However, the maddening intensity of motorbikes heeding no traffic regulations discourages extensive walking.

The next day’s visit to the Chu Chi Tunnels began with a documentary film. The underground maze was dug in 1945 to serve in the fight against the French, and was expanded over twenty-five years by the Viet Cong. Spanning 125 miles the multi-level tunnels hid thousands of fighters and villagers while the country was at war with the Americans. We went down through a narrow opening widened for tourists, where we saw an operating room, a meeting room, a mess hall, and a kitchen. Smoke from the kitchen was deflected into bamboo chimneys that doubled as traps, causing victims to fall in when pulled. Doors between tunnels prevented poisonous gas poured in by the enemy from traveling to other units.

The tunnels narrowed at the center to capture Americans in case they were successful in entering. The Viet Congs’ small frames as opposed to the Americans’ big stature played a role in strategic planning. Women worked in the tunnels during the day and in the rice fields at night in order to feed the soldiers. They dipped rice rolls in crushed peanuts to provide protein. Since my previous visit, I found the bunkers easier to access and in general more visitor-friendly; the souvenir shops had tripled in size and number. The tunnels are a vivid testament to the ingenuity and perseverance that eventually helped the Vietnamese win the war, and are definitely worth a visit.

On the way back we stopped by a forest of rubber trees. These trees, planted in neat rows, have a life span of forty years. Just before the rainy season, the bark is scored for the sap to drain into clay pots tied to the trees. Several times a day the pots are emptied and the rubber taken to a latex factory to be used in the manufacture of tires, mattresses and other products. Rubber is Viet Nam’s main export item, along with crude oil, rice, coffee, tea, garments and shoes.

Visiting a family business for making rice paper was the beginning of a culinary adventure. Women spread boiled rice flour thinly over a hot plate until it formed a round film of dough, which then was wrapped around a wooden dowel and spread on a bamboo screen to dry. Lunch was at the Saigon Culinary Art Center. The menu consisted of dumplings with shrimp, a lotus stem salad with pork and shrimp, braised chicken with ginger, sour soup with ginger, steamed rice, tropical fruit and tea; everything was delicious.

A visit to the Tayson Lacquer Shop helped us to understand the complex and time-consuming craft of lacquer ware production. The process of making an object begins with bamboo being split and coiled into a traditional shape, which is then coated with a lacquer paste made of sap from a tree indigenous to Southeast Asia. The bamboo is then cured for a week in a dark, humid room. After several lacquer coats alternating with week-long cures, the object is ready for rinsing, polishing and incising. Incising for each successive color is followed by washing, polishing and a final buffing. This shop used three different techniques for the application of images: painting, filling with mother-of-pearl, and pressing in cracked duck egg shells. The results were exquisite. I bought a silver-on-black painting of a fisherman in a boat pulling his net, rendered in cracked egg shells.

The evening adventure was a rickshaw ride through town on the way to a traditional water puppet show. My driver negotiated the mayhem of cars, motorbikes and buses as they converged at intersections, making their way through without the aid of traffic police or lights. As we sped by, I tried to photograph sidewalk vendors with goods heaped in baskets, along with billboards and advertisements in neon lights vying for attention on building facades. Every luxury brand of Japan, Europe and the US beckoned passers-by to shops with enticing displays, while karaoke signs blinked up above.

The water puppet show was just as delightful as the one I had seen in Ha Noi during my previous trip. To the accompaniment of live traditional music and singers, providing the puppets’ voices at either end of the stage, colorful puppet dragons, lions, frogs, ducks, fish, unicorns and people performed humorous tales from folklore as they played, danced and frolicked in and out of the water that was their stage. Standing in water, eight puppeteers in hip-length rubber boots manipulated the puppets, which were attached to long poles, from behind a screen. This form of puppetry is unique to Viet Nam and is a treat for all visitors.

Dinner after the show was at l’Etoile, a five-star French restaurant, one of many in town. The haute cuisine menu included homemade bread and butter, soup and fresh salad with pâté chaud, filet of sole and baked banana with sherbet for dessert. Viet Nam was part of French Indochina from 1887 to 1954, which accounts for the many French restaurants.

The morning view out of my hotel room window was a spectacle of people exercising. At 5 am people were in the park, doing tai chi or aerobics. With a lively night life, which continues to all hours without the intense heat of the day, the city never seems to sleep, but pulsates twenty-four hours a day.

On our way out of town, we stopped at a stone carving shop, where we watched craftsmen at work. The store and its grounds displayed various statues of the Happy Buddha. Though the Communist government used to discourage the practice of religion and 80% of Viet Nam’s population of 86 million are non-believers, the culture is permeated by Buddhism, whose teachings of happiness and contentment influence daily life. 9% of the nation are practicing Buddhists.

Heading south to the Mekong Delta, we drove through the new residential areas of sprawling Ho Chi Minh City. Million-dollar villas and giant supermarkets dotted the landscape amidst canals covered with lotuses, the national flower. Due to expanding industry in the city center and a growing population, unplanned development is transforming the surrounding landscape.

In the short span of five years between my visits, I found the vibrant Ho Chi Minh City to have become even more furiously active and commercial. The streets are filled with new motorbikes and taxis; downtown boulevards glitter and shimmer with state-of-the-art advertising. Contemporary buildings are crowding out the characteristic older thin houses with narrow facades and storefronts. Since urban dwellers lost everything when they were forced to become farmers under the Communist regime in 1975, their eventual return to the city and economic liberalization have created a new class of entrepreneurs. They and the city are definitely making up for lost time at a dizzying speed.