100 Boston Artists by Chawky Frenn

New Book Follows 100 Boston Painters

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 16, 2013

100 Boston Artists

By Chawky Frenn

Essay by Debbie Hagan

ISBN-13: 9780764344039

Publisher: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.

Publication date: 7/28/2013

Pages: 224

From Colonial times, through the American Impressionists tradition that tapered off in the late 1920s, the history of the fine arts in Boston has been chronicled adequately. The Museum of Fine Arts has organized a number of thematic surveys and exhibitions of major individual artists accompanied by scholarly publications. These overviews include New England Begins: The 17th Century, Paul Revere’s Boston, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940 and The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930.

There has been no such effort by the MFA to acknowledge the largely Jewish and immigrant artists that comprised Boston Expressionism. That movement germinated during the Depression years of the 1930s, survived World War II, and then dominated the visual arts in Boston during the post war era of the 1950s. The DeCordova Museum organized Expressionism in Boston, 1945-1985. The Fuller Museum of Art exhibited a retrospective for Hyman Bloom and the Danforth Museum, under current director Katherine French, has focused on the legacy of these artists. During the opening of the MFA's contemporary wing the museum stated a renewed comittment to that field.

Compared to the New York School and abstract expressionism the visual arts in Boston is of token interest on a national and global level. Despite the vitality and progress of the past few decades, arguably, contemporary art in Boston attracts scant national curatorial or media attention.

For a time, curators of the Whitney Annual, later the Whitney Biennial, made pro forma whistle stops through Boston resulting in a few artists being included in their national surveys of American art.

With little or no institutional support, and few significant collectors, the career prospects for Boston based, contemporary artists have been slim. It is, however, a great city in which to live and work with a broad spectrum of museums and cultural recourses. With its unique spectrum of art schools, private schools, colleges and universities many artists survive by teaching.

The density of institutions of higher learning also comprises a critical mass of intellect and research. This has uniquely informed the fields of art/ science/ technology as well as photography and more recently video/ digital, conceptual, and installation arts.

Primarily, however, Boston is noted for aspects of handmade art primarily in the traditional approaches of painting, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture. While the overview of the fine arts in Boston is conservative there is a substratum of artists, primarily students and emerging artists, that is stridently edgy and experimental.

While there have been pop up efforts to cater to this creative energy it is not enough to sustain as an incubator of developing artists. Not long after completing degree programs most young artists move on. Within a decade the vast majority of emerging artists are out of the field. Which is true no just in Boston.

This turnover is so rapid and quixotic that it is impossible to document. Those who could are caught up in the struggle to survive. The few who are noted in sporadic group exhibitions, pop up alternative galleries, publications and histories have grabbed the brass ring and held on for a few spins on the critical and curatorial merry-go-round.

During the late 1960s it was possible for a generation of emerging artists to gather in one room. That’s what happened when the artist couple Andrew Tavarelli, and his then wife now Jane Hudson, hosted a seminal dinner party.

I had started writing a weekly column for Boston After Dark (later renamed the Boston Phoenix) called Art Bag. Having returned from three years in New York City, where I worked for art galleries and wrote reviews for Arts Magazine and then Avatar in Boston, I was anxious to meet artists.

The Boston I had grown up in was conservative in its approach to the visual arts. There were the annual Boston Arts Festivals with their tent show exhibitions. Newbury Street was anchored by the Copley Society, Vose Gallery, Childs Gallery and the Guild for Boston Artists. Previously there had been the progressive Margaret Brown Gallery. The primary gallerist showing advanced work, The Boston Expressionists and artists inspired by them, was Boris Mirski. Hyman Swetsoff had a more progressive program which ended when he was murdered by rough trade.

There was a new energy marked by Drew Hyde, hired in 1968 to run Summerthing, a city based community effort which promoted building neighborhood parks (designed by architect Edwin Childs) and commissioned murals in public places. When that gig ended Hyde took over the then moribund Institute of Contemporary Art warehoused in a defunct, failed, former building on Soldier’s Field Road. For a variety of reasons the struggling ICA, under Sue Thurman, had been evicted from Newbury Street.

There would be changes of directors, visions and venues leading to the spectacular new permanent home of the ICA on Boston’s waterfront.

From that seminal dinner party evolved the momentum to organize the first ever open studio event The Studio Coalition. That in turn motivated the Obelisk Gallery to join with Harcus Krakow Gallery to open the vast space Parker 470 across from the Museum of Fine Arts on the Roxbury side of Huntington Avenue.

That ambitious gallery became a gathering place for artists with a series of discussions and meetings, including one with then MFA director, Perry T. Ratbone. Those meetings gelled into the Boston Visual Artists Union (so named by Elizabeth Dworkin). There was in the infamous Flush with the Walls happening in the basement of the MFA. It was restaged in 2011. Not long after that Rathbone called me at the Boston Herald Traveler to announce the appointment of Kenworth Moffett as founding curator of the Department of 20th Century Art.

As part of the research for a biography of her father Belinda Rathbone interviewed me about those events for which she had a different interpretation. The book went to press last November. We also are in the process of a dialogue with Moffett about his tenure at the MFA. There are different versions of how that occurred.

As the 1970s progressed there were so many arts organizations, university, college and commercial galleries that it was no longer possible to count heads and keep track of Boston’s movers and shakers.

Given the depth, range and diversity of the current scene Chawky Frenn, a Lebanese born, figurative artist and professor at George Mason University, has taken on the seemingly impossible task of publishing books that attempt to capture lightning in a bottle.

His first book 100 Boston Painters, for which I wrote the primary essay, has now been followed by 100 Boston Artists. The new volume from Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., using the same format and design, features an essay by former Art New England editor, Debbie Hagan.

While welcoming input from gallerists, collectors, curators and critics, yet again, the final selection of artists has been curated by Frenn. The result is that the volumes are quirky and eccentric. Both praise and blame belong entirely with Frenn. Bravo for having accomplished the impossible; creating useful, attractive publications with superb reproductions. And blame for not delegating to jurors who are experts in the field.

The selection, reflecting the taste of a representational painter, includes many important individuals as well as a lot who are not. In the introduction Frenn states “…I make no claim that these are the most acknowledged artists in Boston. In fact, I feel honored to include artists with a wide range of reputations from the known and famous to the obscure and hidden. I am fortunate to know and to acknowledge artists who, for years, have worked diligently under the radar of the art establishment; it is my desire to uplift their wonderful creations. It is not the responsibility of artists to seek recognition, but it is the obligation of the critical community to recognize worthy artists. Therefore my selection includes artists who are not necessarily well known.”

That greatly diminishes the historical value of the publications. There were similar, flawed but entirely professional efforts by the De Cordova Museum to mount exhibitions with scholarly catalogues Painting in Boston: I950 -2000 and Photography in Boston: 1955-1985. For research on contemporary art in Boston there are the Boston Now catalogues of the ICA, lists of the Boston Triennial mounted by the former Fuller Museum of Art and The DeCordova Biennials (the 2013 version opens on October 9 through March). There is the important MFA catalogue by Edmund Barry Gaither Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston. The New England issues of the curated publications, New American Paintings, are useful for collectors and scholars. One might consult winners of the Maud Morgan Prize of the MFA, and the once annual Foster exhibitions of contemporary Boston artists curated by Carl Belz for the Rose Art Museum.

Back issues of Art New England are an invaluable resource. The Real Paper, The Cambridge Phoenix, Boston After Dark and the Boston Phoenix published serious art criticism. The Boston Globe less so other than the too brief tenure of Ken Johnson and currently by Sebastian Smee.

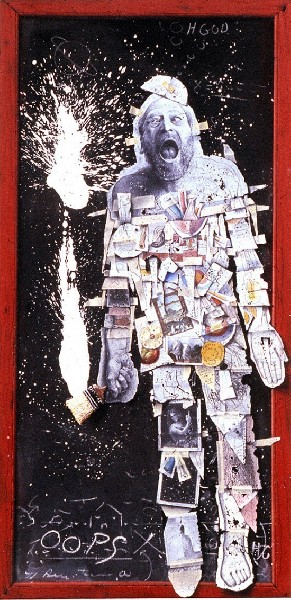

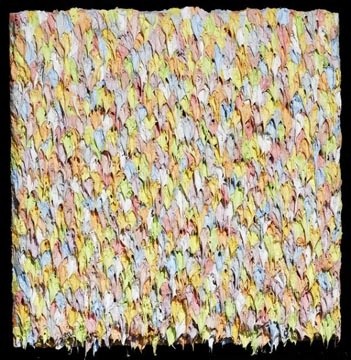

Actually, 100 Boston Artists most resembles the format of New American Paintings. The artists in alphabetical order are each given two pages including illustrations of their work, an image of the artist, and a brief artist statement. There is one page of 99 notes for those statements. Interestingly, the 100th artist at the end, under “The Author,” is Frenn who has juried himself into the book. "The Artists" has entries for the artists with gallery and contact information. There is also an incomplete list of Massachusetts Galleries ( some from Cape Cod and none west of the Clark Gallery in Lincoln).

Most significantly there is no bibliography. As an artist/ curator Frenn had no interest in creating a publication promoting further scholarship in a field where it is much needed.

The essay by Hagan is fresh, interesting and well written. As a preface to the discussion of some but not all of the artists she provided a bit of history starting with the Puritan John Winthrop and an anecdote from 1630. Then the essay fast forwards to Dushko Petrovich’s “How to Start an Art Revolution: A Manifesto for Boston” which was published in the Boston Globe in 2010. There is a cut back to the Harvard Society of Contemporary Art in 1928, members of which, later founded the Museum of Modern Art and the Boston Museum of Modern Art. The latter, in a famous break under founding director James Plout, became the Institute of Contemporary Art. MoMA thrived but the ICA did not.

The first of Frenn’s two volumes was 100 Boston Painters. But it is a struggle to understand exactly how 100 Boston Artists is different. It again includes many painters, notably, a number of important ones who should have been included in the first book.

In addition to painters the second book also includes photographers, sculptors, the renowned first generation Studio Furniture master, Judy Kensley McKie, and a single example of multi media/ conceptualism, the brilliant Rachel Perry Welty.

Hagan makes no attempt to explain or justify Frenn’s selection, indeed, how could she as it is so irrational? Rather, she focuses on a comfort zone of artists she clearly admires, and rightly so, as well as some unique phenomena such as the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT. Its founder, Gyorgy Kepes, is included in the book. She discusses the German born Otto Piene who she states was the founder of Group Zero. It would be more accurate to say one of the founders. While Piene has been given numerous retrospectives in Europe, and a major monograph, he has rarely been show in Boston. I exhibited his drawings in the gallery of the New England School of art and he was included in a recent DeCordova Biennial. But despite lobbying he is not included in this book.

But CAVS holographer, the late Harriet Casdin Silver has been recognized. None other of many fellows of CAVS has been represented. CAVS was a major phenomenon, of global signifiance, which continues to be ignored by the Boston Art World.

There are some photographers. Hagan discusses the importance of Harold “Doc” Edgerton a pioneer of strobes who was a major 20th Century American photographer. Frenn apparently does not agree. Hagan did not mention Minor White who taught a generation of important photographers at MIT.

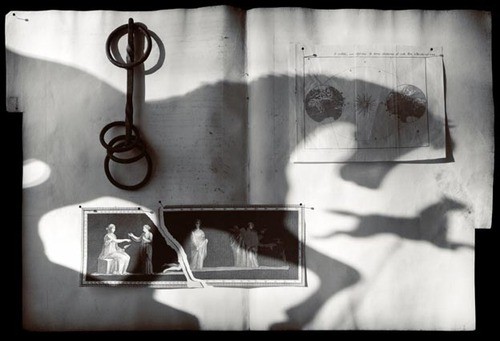

Photography in Boston has always been remarkable with many individuals enjoying national reputations. Indeed we need a book 100 Boston Photographers. This volume touches the tip of the iceberg including among others; Bill Burke, Casdin-Silver, Jesseca Ferguson, Kepes (represented by his paintings but an important photographer as well), Olivia Parker, David Prifti, Daniel Ranalli, Dana Salvo, Robert Siegelman, Doug and Mike Starn.

On the positive side a new history has the ability of correcting mistakes of previous ones. The Starn Twins, for example, where not included in the DeCordova’s book on Boston photography. They are included here. At the time I asked the curator Rachel Rosenfield Lafoe about the Starns and Mark Morrisroe, also a student at the Museum School (in Lia Gangitano’s The Boston Band at the ICA along with Jack Pierson and Nan Goldin among others) and why they were not included. She said “I don’t think they were important.” Once again, Morrisroe, who is thought of as one of the most original and influential photographers of his generation, didn’t make the cut.

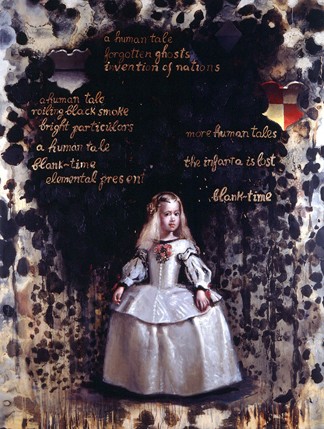

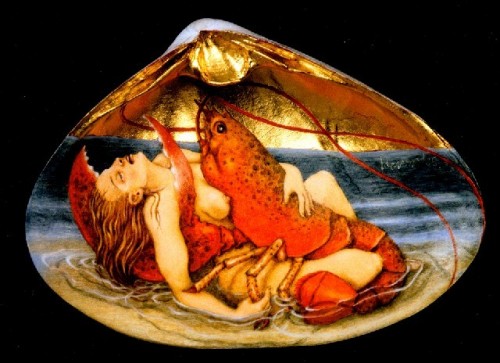

It is gratifying that this time around some wonderful painters have been included, among others- Domingo Barreres, Thaddeus Beal, Susan Jane Belton, Gerry Bergstein, Linda Etcoff, Masako Kamiya, Kepes, Bryan McFarlane, Martin Mugar, Dean Nimmer, Barnet Rubenstein, Dawn Southworth, Paul Stopforth, Lois Tarlow, Andrew Tavarelli, Bill Thompson and Tabitha Vevers.

The selection also includes sculpture. There is a unique gallery in the South End Boston Sculptors. More of those artists deserve recognition and sculpture is a not well curated aspect of the book. Some exceptions are Sachiko Akiyama, Doug Bell, Mark Cooper (a recent ICA finalist), Kahlil Gibran (nephew of the poet), Mags Harries, Ralph Helmick, Chuck Holtzman, David Phillips, Welty, Joseph Wheelwright and Andy Zimmerman. Missing are Penelope Jencks (Admiral Morrison sculpture on Commonwealth Avenue), Harold Tovish, and Dmitri Hadzi.

While these two handsome books are a step in the right direction there remains much to be done in telling the rich and complex story of contemporary art in Boston.