Summer Retrospective I: The Bard Music Festival: Franz Liszt and his Times

In Search of Liszt

By: Michael Miller - Sep 18, 2006

The Bard Music Festival, now in its eighteenth year, "traditionally surveys the world around a single composer—teachers and followers, friends and enemies, advocates and critics," as the richly annotated and illustrated program explains. For those unfamiliar with this excellent initiative, one might add a little more. Filling three weekends, two in August and one in October, the Festival offers a combination of concerts and recitals, each bringing together a variety of instruments and ensembles, pre-concert lectures intended for the general public, and academic symposia with speakers drawn not only from the most prominent specialists in the field, but including experts in significant ancillary fields: history, art history, etc. As if this weren't enough, Bard offers an operatic production (Schumann's fascinating "Genoveva" this year, which I have already discussed) related to the composer of the year, as well as other, more loosely related events. What's more, each festival involves the publication of a collection of scholarly essays, which was available for purchase on the opening evening. Usually sold out or close to it, the Bard Music Festival is without a doubt the richest and most valuable summer event in our region.Since the Festival is actually a hybrid of the summer music festival and the academic conference, it has a quality all its own. While the Saturday and Sunday evening performances bring in their share of serious laymen and well-heeled summer people from banks of the Hudson, the morning and afternoon concerts (held in Bard's smaller, acoustically outstanding Olin Hall) are largely attended by the conference-goers, and a cheerful academic atmosphere pervaded the air, most apparent in the collegial roar in the lobbies during the breaks. Interestingly, the audience, while greying as at all classical events, were noticeably younger than those at our usual summer festivals. This demographic feature must reflect the fact that the academic element in the Festival brought visitors who had not yet retired, although they appeared to be mostly senior members of their departments. I hope the scarcity of younger faculty, who could most obviously have benefitted, didn't mean that travel funds were restricted to the loftiest ranks, although the alternative theory that younger musicologists aren't interested in Liszt, is far more distressing. The Festival, with its far-reaching scope, is an effective antidote to the overspecialization that plagues younger academics. I suppose it speaks well for the discipline that so many musicologists have snapped up the opportunity to hear both the familiar and the obscure offerings of the Festival. I remember meeting a musicologist once who couldn't tolerate the vagaries of musicians and confined himself to reading scores. The academic audience were clearly enjoying themselves. One has to admit that it wouldn't be terribly difficult to hear most, if not all the works on the program on recordings, but these are live performances, and the event brings people together.

In any case, this year's composer, Franz Liszt, made my visits to the Bard Music Festival something of a quest. I was looking for enlightenment, because Liszt has always been an enigma for me. This German-speaking cosmopolite from a town in western Hungary which now belongs to Austria, legendary piano virtuoso and lover, pioneer media celebrity, artistic revolutionary, composer of grand works, deity of Weimar, member of a Franciscan lay order, father-in-law and supporter of Richard Wagner, teacher of great pianists of the following generations, some of whom survived into the age of sound recording, was one of the most significant cultural figures of the mid-nineteenth century, an icon of Romantic flamboyance, experimentation, transcendentalism, and vulgarity. Liszt's renown has not survived to our times without acquiring its share of disrespectability, and truth is, he did compose some very bad music and his youthful attitudinizing has been seen as embarrassing by more than one generation already.

I have a distant memory of sitting in music class in elementary school, shifting in my seat, while our demented teacher gave a simpering account of Liszt's flamboyant life (bowdlerized so as not to elicit havoc from a classroom of pre-pubescent boys) and played a scratchy lp of Liszt's First Piano Concerto. Not long after, as I began to develop an interest in music, I tried to appreciate it. Later as I learned a little more, I ridiculed it, and all Liszt's music I'd never heard. Much later, his better work, like "Les Années de Pélerinage," began to appear on concert programs and on records, and I heard musicians like Louis Kentner and Alfred Brendel reveal the best of Liszt, and the best in him. Over the years more and more intelligent musicians like Russell Sherman, Jerome Rose, and Daniel Barenboim have taken up the cause. Recently, now that I make a point of going to hear young pianists and competition winners, I realize that Liszt's display pieces are very much alive in this province of the music world, and they are great fun to hear. (If you are in doubt, click here.) Still, none of Liszt's works are exactly the concert staples they once were. However, there is no doubt that he stands as one of the most important and representative figures of his time. He not only delved into pretty much every aspect of music, he struck roots in politics, religion, theater, the visual arts, as he evolved from the virtuoso who made women faint in their seats to a universal cultural guru, as, later in life, he presided over the elaborate ceremonies which took place around the inauguration of monuments erected to giants like Goethe and Beethoven. Finally, he appears to have been a good man, however vain or inconstant. Above all he left behind numerous memories of kind and generous acts, both for charities and for friends. I came to the Festival with a genuine need and desire to know Liszt's life and music better.

I'll now try to chart a course through the rich offerings of the two August weekends, noting that I was not able to attend everything. You can imagine my irritation as I sat through a lackluster Brahms concert at Tanglewood with the usually excellent Peter Serkin, who was sadly let down by the slick Pinchas Steinberg, brought in to replace an indisposed Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, when I could have been at Bard!

Another point worth mentioning here is the salutary effect of events like the Bard Festival in countering the consumerism which dominates mainstream classical programming, both in the concert hall and on disc. In our contemporary culture it's easier to market a sexy young violinist than a familiar composer, whose name conjures up plaster busts or sad tales steeped in the mores of bygone times, when people looked askance at children born out of wedlock and women who wore trousers and smoked cigars, and kings and struggling composers alike had to bear the burden of syphilis. We all came to Bard to hear Liszt, not any touted performer, but the performances, most by young and mid-career musicians unfamiliar at places like Tanglewood, were almost all at a very high level, and some were truly unforgettable. It was clear that the organizers of the Festival, Leon Botstein, Christopher H. Gibbs, and Robert Martin, had excellent reasons for inviting all of the musicians who contributed—the singers, soloists on various instruments, and above all the pianists. Aside from that, it never ceases to amaze me how different a single piano can sound when played by a variety of pianists during the course of a concert, or a day of concerts.

As a result, if I ever see a recital advertised with any of these names, I'll drop pretty much anything to go: Valentina Lisitsa, Arnaldo Cohen, Chu-Fang Huang, Ieva Jokubaviciute, Orion Weiss, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Jeremy Denk, Anna Polonsky, Piers Lane, Martin Kasik, Diane Walsh, Melvin Chen, Michael Abramovich, Konstantin Scherbakov, Peter Orth, piano; Sara Cutler, harp; Ani Kavafian, Alexander Markov, Giora Schmidt, violin; Sophie Shao, cello; Nicole Cabell, soprano; Jill Grove, mezzo-soprano: Philippe Castagner, Michael Hendrick, tenor; Andrew Garland, John Hancock, baritones. What's more, Botstein's American Symphony Orchestra is an excellent ensemble, always musical and responsive to his insightful direction.

Were there stars? Absolutely. Violinist Alexander Markov gave an astonishing performance of Paganini's "Caprices." Soprano Nicole Cabell sang Liszt's setting of Heine's "Die Lorelei" with penetrating intelligence and heart-rending expression. Ani Kavafian and Jeremy Denk, both members of the Bard music faculty, gave a fiery and richly nuanced performance of Grieg's Sonata No. 3 in C Minor, which I'll remember as one of the all-time great chamber performances I've heard. The next day Denk played the Sonata in b minor, arguably Liszt's finest work, with singular understanding and intensity. In constructing this single movement piece Liszt superimposed the fast-slow-fast pattern of a three-movement work over a traditional sonata form. The complexities of this double structure, as well as Liszt's interweaving of thematic motifs, resonate throughout the work and have been discussed extensively in the literature without any consensus emerging. In studying this work Mr. Denk clearly pondered this problem in some depth. I've never heard a more intelligent or powerful performance of the work, and this includes Kentner and Brendel. Mr. Denk showed that he has already achieved that exalted level of musical thinking with brilliant technical ability. For me this was this high point of the Festival, and the rest of the audience seemed to agree. This was an afternoon performance, and the standing ovation came from an Olin hall full of leading Lisztian scholars—a dream audience, if you're up to it. Can you imagine what that means not only to Mr. Denk, but to the other musicians who performed at the Festival?

What impression of Liszt did I take away from the Festival? A youth of strong spiritual impulses, he developed his talent for the relatively new and rapidly evolving fortepiano, following the model of Paganini, to make himself an idolized virtuoso. Associating himself with opera, the most popular form of higher public entertainment, his gifts as a performer enabled him to reproduce the thrills of grand opera in the salons and rented opera houses in which he gave his recitals. One could say he took it a step further: at the piano he exaggerated the gestures of opera. At the crucial age of thirty-five he gave up concertizing to settle at Weimar, an old-fashioned ducal town with a powerful cultural aura, Goethe's city, where he conducted, composed, and taught. He developed the authority of a great cultural hero. He returned to his spiritual roots with his increasing devotion to Catholic faith and musical tradition. One of the great discoveries of the Festival for me was his lovely and deeply felt liturgical music for chorus. I believe he survives as a composer through his mastery of mood, atmosphere, and drama, but above all form. He could seemingly toss it away in his more improvisational works, but he cold also weave complex organic constructions like no one before him.

Opera is the key to Liszt's early career. His digests of opera tunes, which he usually called "Réminiscences," were the stock in trade of his virtuoso performances—a development of the variations on operatic arias which Beethoven, like many other composers of the time, took up early in his career. The Festival began with one of the better of them, the "Re´miniscences de Don Juan." Valentina Lisitsa applied her formidable technique to this old war horse, making her case for it with musicality and wit without attempting to hide its occasional superficialities. In her execution of the ornaments in the section based on "La ci darem la mano" one could easily picture Liszt's crowd-pleasing gestures at the keyboard. I should mention that Russell Sherman performed this work at Monadnock last year, creating a grand effect as Mozart's music took shape out of the turbulent introduction and presenting Liszt's treatment as a Proustian essay in musical reminiscence, suggesting that it is not without its "profondeurs."

The first concert included a selection of Liszt's songs, a genre in which he excelled, I believe. His settings are always striking and original, sometimes disarmingly simple and intimate and sometimes grand, employing operatic modes like recitative in a way that penetrates to the heart of the text, here masterfully sung by John Hancock and Nicole Cabell. Peter Orth and Konstantin Scherbakov gave penetrating readings of some of Liszt's more substantial piano works, including his ekphrasis of of Raphael's altarpiece, the "Sposalizio," and "Harmonies du Soir," one showing his close involvement in the visual arts and the other the depth of his own poetic creation. The evening closed with beautiful examples of his ecclesiastical choral writing, but for me the great revelation of the concert was "Am Grabe Richard Wagners," a meditation on the character, life, and music of his son-in-law, Richard Wagner, who predeceased him by three years. One could think of this short piece as a somewhat vague "Réminiscences de Parsifal," but here Liszt's mysticism is unquestionably sincere and profound.

I can only express my regret at missing the the second day, which included one of the most important events of the Festival, a reconstruction of "Héxameron," a notoriously difficult set of variations on the march from Bellini's "I Puritani," based on newly examined manuscripts.

I took up the thread again Sunday morning at 10 am with Lisitsa's splendid performance of "Réminiscences de Robert le Diable," a weaker and showier piece than "Don Juan." This was followed by a string of short pieces and excerpts by Liszt's virtuoso contemporaries and pupils. The title of the concert was, after all, "Virtuosity Blowout." Worth particular mention is Melvin Chen's atmospheric reading of Carl Tausig's "Das Geisterschiff" ("The Ghost Ship"), his and cellist Sophie Shao's polished performance of David Popper's Mendelssohnian "Elfentanz" ("Dance of Elves," a delightfully silly composition), and David Abramovich's sensitive playing of a Rubinstein etude.

The afternoon concert "Virtuosity Transfigured: in the Shadow of Paganini" offered an absolutely brilliant performance of selections from Paganini's "Caprices," Op. 1 by the Russian violinist Alexander Markov, followed by Martin Kasik's sensitive playing of piano transcriptions (really free interpretations) of some of the Caprices by Liszt and Schumann. The concert ended with Diane Walsh's insightful performance of Brahms' Paganini variations, Op. 35. Her large but mellow sound gave an orchestral impression. For once musical expression governed the flow of the music, not rhetorical gesture. As the commentator Jim Samson pointed out, we were all ready for some Brahms. I should also not fail to mention the moving and original reading of a movement from one of Bach's violin partitas, which Markov offered "to calm our nerves."

The evening program was also a blowout: "Grand Opera before Wagner." Leon Botstein led the American Symphony Orchestra, the Bard Festival Chorale, and a group of singers, including Nicole Cabell and Philippe Castagner, who distinguished himself as Golo in Schumann's "Genoveva' a few weeks before, in a spirited and very loud concert of excerpts from the most popular operas produced in Paris while Liszt lived there as a young man. Most of these works by Rossini, Meyerbeer, Halévy, Auber, Donizetti are known merely from history books today, as famous as they were in their own time. Exceptions were Rossini's Overture to "William Tell" and Bellini's "Norma" which was itself forgotten until Maria Callas made a vehicle of it in the 1950's. At one time a concert like this would have been the only way to hear this music, but today all of these operas are available in good recordings. Schumann, who detested this kind of opera, especially Meyerbeer, was, it seems, a prophet of twentieth century taste. The orchestra's playing was splendid. The lyrical opening of the William Tell Overture with its split cellos was especially eloquent. The only disappointments of the evening were soprano Olga Makarina's not unattractive, but undistinguished singing, painfully apparent in her singing of Norma's "Qual cor tradisti," an aria well known to most in the great performances of Callas, Sutherland, and Caballé, and one of two student conductors who did brief turns at the podium. Otherwise both audience and performers had great fun. If Liszt was able to conjure up this fabulous operatic world at the keyboard, he was indeed a great showman, in fact, a genius of a showman. We should not forget that P. T. Barnum wanted to bring him to America to tour in his show.

The Festival continued the following weekend with two programs devoted to nationalism in music, one general, one devoted to "Hungarian" music, which never really existed in the nineteenth century. It was rather a pastiche of gypsy music. In these Chu-Fang Huang and Piers Lane excelled with their intelligent playing of Chopin, Liszt, and others. Huang balanced powerful dynamics and incisive phrasing with a singing line and graceful flow, and Lane distinguished himself with an extremely appealing lyricism. Friday evening included Kavafian and Denk's Grieg, as well as a rather disappointing performance of Smetana's seldom heard, but very beautiful second string quartet, a particularly challenging piece with its weave of exposed independent lines in all four instruments. It merits and requires a performance by an absolutely top quality quartet who have been perfecting their ensemble over years. From Saturday morning I must mention the sensitive performance of a movement from Schubert's great "Divertissement àl'hongroise" for piano four hands by Orion Weiss and Ieva Iokubaviciute. Their perfect ensemble and flexible expressiveness made this one of the very best performances of its kind I have heard. I regretted not hearing them perform the entire piece. Otherwise the liberal inclusion of excerpts proved an effective way to juxtapose the work of different composers for didactic purposes. As Dr. Botstein pointed out in his introduction, Bard Festival programs are "curated."

The afternoon was devoted to chamber music by various contemporaries of Liszt, concluding with his great Sonata in b minor, so magnificently played by Jeremy Denk. Interestingly, The Sextet in g minor by the diligent Joachim Raff showed that Mendelssohn's influence was still alive in 1872, a quarter of a century after his death.

The Saturday evening program, "Christ and Faust," which was unfortunately the conclusion of my experience of the Bard Festival, was a substantial program, which included a choral arrangement of Schubert's song, "Die Allmacht," the "Flight into Egypt" from Berlioz' "L'Enfance du Christ," "The March of the Three Holy Kings," an elaborate movement from Liszt's "Christus," and his important orchestral work, "A Faust Symphony in Three Character Pictures after Goethe," to cite its significant full title. If Liszt murdered Schubert's "Der Erlkönig" in his bombastic piano transcription, "Die Allmacht" fared much better, with its dialogue between tenor solo and chorus, sensitively sung by Michael Hendrick. The influence of Berlioz's beautiful "Enfance" is clear enough in Liszt's oratorio, "Christus."

Alan Walker, the doyen of Liszt studies, in his introductory talk, put me on my guard with his high praise of Sir Thomas Beecham's pioneering recording of the Faust Symphony. Although I did not know it at the time (I do now.) I felt that Dr. Botstein and the American Symphony had their work cut out for them. It isn't easy to compete with Sir Thomas. Dr. Walker also told the story of how Liszt composed the Faust Symphony with uncharacteristic rapidity, assisted by a special organ which could reproduce a vast range of timbres. It appear to me that this was Botstein's point of departure in his superb reading of this complex and forward-thinking score. The American Symphony rendered Liszt's unusual and varied orchestral colors with exceptional precision. I could easily imagine the composer testing out his sonorities with his organ. The clear textures balanced by rich tutti and wide dynamics further helped bring Liszt's ambitious purposes across. In view of what Dr. Walker said about Beecham and his imitators, I can say that Dr. Botsein proved himself very much his own man in this performance. For example, Beecham's treatment of the second movement, "Gretchen," is more operatic and lyrical, stressing the character's humanly loving nature. In Botstein's reading, she is more ethereal, absorbed by the otherworldly Christian love expressed through Liszt's unearthly orchestral sonorities. I should add that Berlioz' influence show itself here once again.

Modern listeners prize Liszt because so much of his music was ahead of its time in his use of harmony and tone color. In "A Faust Symphony," in which he gives an impression of Goethe's drama through three different character studies, he anticipates the musical characterizations of Strauss and Berg with all the imagination of which his genius was capable. Curatorially speaking, "Faust and Christ" touches on the two essential traits of the self-image of this enigmatic man. If Liszt, as a Christian of profound faith, loved and emulated Christ, he indubitably saw himself as Faust. When he first composed "A Faust Symphony," it ended with the portrait of Mephistopheles. His addition of the Chorus Mysticus a few years later points to the dichotomy indicated by the concert title. While he might be captivated by Faust's Luciferic genius and his joie de vivre, he could not, as a Christian, forgo redemption, attained in typically Lisztian fashion through "das ewig Weibliche." Furthermore, if one were to take "A Faust Symphony" as a self-portrait, it is striking that he needed four movements devoted to the major characters of Goethe's drama to achieve this: Faust, Gretchen, Mephistopheles, and, of course, God.

The Festival was comprehensive but not exhaustive. With a figure as complex as Franz Liszt, how could it be? For my part I should have liked to have had an evening devoted entirely Liszt's songs. I believe he really excelled in this form, in which he managed to avoid his usual vices and showed a particular talent for getting straight to the essence of a text—in his own personal way. Take for example the Petrarch setting, "I vidi in terra angelici costumi" and "Vergiftet sind meine Lieder" by Heine. Liszt appreciated literature as keenly as Schumann or Schubert, and one of the conference sessions could well have included a paper on his reading and his relationship to literature in his music. The subject has hardly been neglected in the past, but in such a case there is always room for more.

Then, I found it a little odd that there was no attempt to include any period instrument in the concerts or to discuss the issue at length in the sessions. The instrument evolved from the fortepiano to the modern piano during Liszt's lifetime, and, as a performer and teacher, he had an exceptional influence on its development. As a young man he would have played on a Viennese instrument similar to the Regier "Grafendorfer," which was heard twice in the Berkshires this summer. In his maturity he favored Érard pianos from Paris. An Érard from the early 1860's which belonged to Liszt was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2002, and one can listen to a recording of it on the museum Web site.

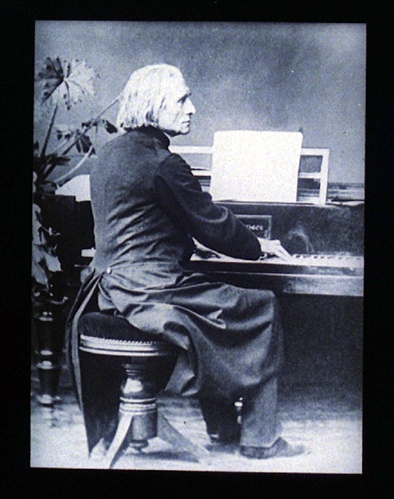

I have saved a few observations on the scholarly component for last. The one conference session I was able to attend was interdisciplinary in its intent, and including contributions on the history of art and architecture, as well as one by a feminist scholar on Liszt as a celebrity. Here the broad humanistic principles of the Festival dissolved into vagueness. Dana Gooley, a respected younger Liszt specialist, grounded the session with a discussion on Liszt as a virtuoso, and Esther da Costa Meyer read a fascinating and thoroughly researched paper on the theatrical presentation of Liszt's music. Katherine Bergeron spoke on Liszt and the rediscovery of medieval plainchant, somewhat problematically. Griselda Pollock's contribution was intelligent and extremely interesting, but somewhat far afield even for Bard's broad contextual ambitions. The extremely interesting topic of the role of images in promoting Liszt's fame as a virtuoso and public figure came up more than once. Much was made of photographs, perhaps too much. Early in Liszt's career the photographic medium would have been the Daguerreotype, which was not cheap. It seems likely that lithographs would have been a practical vehicle for the dissemination of Liszt's public image. A study not only of Liszt's iconography but of the economics and social context of prints and photographs of prominent performers would have answered a lot of unspoken questions at that point. On this note, I should mention that while browsing at Village Books in nearby Tivoli, I found a period photograph of what looked like a plaster cast of a marble bust of Liszt. This distance from original had a rhetoric of its own, exalting the composer's greatness beyond any mere direct portrait.

Each concert began with a talk by one of the conference participants directed at a general audience, that is, more informational than argumentative. Perhaps the talks held in Olin Hall were a little more ambitious that those in Sosnoff Hall in the Fisher Arts Center. There was definitely a sense of colleagues addressing colleagues. Before the evening of opera, Heather Hadley gave what must be her survey lecture on early nineteenth century Parisian opera concentrated into a half an hour. It was solid, informative, and entertaining, like all of the pre-concert talks, including Dr. Botstein's, delivered at the last minute to fill in for a speaker who cancelled. She did not fail to mention the notorious dance of the ghosts of dead nuns in Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable," the textbook example of the questionable taste current in grand opera, with its generous fusion of spectacle, sex, and violence. She only challenged the audience at the very end by pointing out the inherent perversity of the genre—point which underscore the immense distance between the Paris Opera of the 1820's and 30's and contemporary taste, which perhaps tends somewhat to the banal and the prudish. Still anyone who has seen "Braveheart" or the "Lord of the Rings" will have a sense of what grand opera was all about. Jonathan D. Bellman was particularly amusing on the artificiality of "Hungarian" music, greatly amusing the audience with his revelation that the surname of the composer who called himself Márk Rószavölgyi was Rosenthal. I have already mentioned Alan Walker's talk on "A Faust Symphony." Of all the speakers, either in the conference or in the introductory talks, I thought he was the only one to do justice to the seriousness, moral standing, and generosity of Liszt's maturity. Our contemporary obsession with youth and media celebrities who are manufactured for young consumers tended to dominate many of the other contributions. As I listened to Dr. Walker, I finally fully understood why I had come to the Festival.