Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 20, 2013

Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

May 13 to September 7

Deutsche Guggenheim

January 14 to April 27

The Menil Collection

October 3 to January 11, 2004

Curated by Matthew Drutt

Catalogue, 270 Pages, with essays by Drutt, Jean-Claud Marcade, Nina Gurianova, Vasilii Rakitin, Tatiana Mikhienko, and Vevgenia Petrova

The first work that we encounter in this relatively small and tightly focused exhibition of works from the period of Suprematism by the Russian artist, Kazimir Malevich, (1878-1935) is the masterpiece, Black Square, from 1915. It is both riveting and poignant to view this work from the State Tretiakov Gallery, in Moscow, being seen for the first time in the West.

The painting, a solid black square surrounded by a symmetrical border of white, is a ruin. What should have been crisp and pristine is now damaged. The border of white is blotchy and irregular. The black square is finely crackled. The painting has had a life since the artist completed it. It was a composition that he would return to. In a broader overview of the work of the artist, in 1990, at the National Gallery, in Washington, DC there were versions from 1923 and 1929 of this seminal painting.

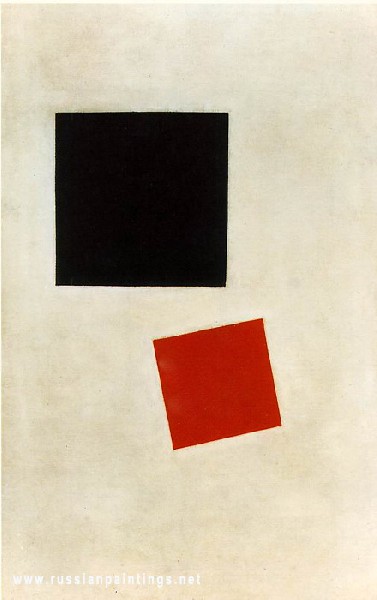

The works of 1915 are particularly important in the development of the radical ideas of the most experimental of the Russian avant-garde artists. He also created circles, slightly skewed crosses, and the horizontal rectangle, Elongated Plane, with slight alterations from 90 degree corners. There are also the important works, Four Squares, two black and two white on a diagonal axis, and Pictorial Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, Called the Red Square. He seemed to evolve from his reductive and grid like formats with, Painterly Realism: Boy with Knapsack- Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension. In that work, suspended in a white field is a black square off center and parallel to the edges of the canvas, below which is a smaller, off kilter, red square. This familiar and often reproduced work from the Museum of Modern Art creates visual tension and dynamic pictorial space.

In, Suprematist Painting: Black Rectangle, Blue Triangle, he edges out of the rectangular again creating an even greater contrast and visual tension. These bold experiments evolve from the simple and reductive to ever more complex and additive with a greater tweaking of forms, shapes and adjustments from the parallel, as for example, Suprematist Painting: Eight Red Rectangles.

From there he evolved an ever more complex syntax of forms and shapes departing, it would seem, from his most reductive, and perhaps most influential impulses. In some respects, this more complex work strikes me as less interesting and gravitates into the domain of other experimental, abstract artists. It begs comparison to his great rival, the far more virtuoso artist, and clearly superior painter, Wasilly Kandinsky, (1866-1944), or the Dutch artist, Piet Mondrian, (1872-1944). Arguably, they were more accomplished painters, but Malevich went further in his pursuit of non objective art.

By 1918, Malevich created an even more radical series, the white on white works, including the, Suprematist Composition: White on White, readily familiar to generations of visitors to MoMA. That single work may indeed be the most controversial and influential painting of the 20th century. He went further than any of the other greatest painters of early Modernism. But he retreated from that position. He pushed experimentation with Suprematism into architectonic models in the late teens and twenties. He and artists of his generation were subjected to immense social and political pressures, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917. This was further complicated by state regulation of the arts and its Marxist repression. Artists were mandated to abandon reactionary, counter revolutionary elitism, follow the guidelines of agit-prop, and conform to the conservative social realism of Stalinism.

After a triumphant exhibition and tour of Eastern Europe, including Poland and Germany, when he visited and lectured at the Bauhaus in 1927, he was later arrested, interrogated and incarcerated for several months in 1930. In the late works he retreated to a form of reductive figuration and portraiture. By then, it was a sad end to the great period of the avant-garde and also marked the years when the great accomplishments of Malevich and his brilliant peers were largely lost to a Western audience.

The works in that 1927 exhibition were entrusted to caretakers and the artist even drafted a will regarding them in the event of his sudden demise. His concerns proved to be well founded. The trustees of these holdings saw to it that the works were acquired by museums. A body of fifty-one works were acquired by the Stedelijk Museum with other works acquired by MoMA and the Provinzialmuseum in Hannover. It is primarily these works, widely exhibited and published, that has formed our basis of understanding the artist and his role in Modernism.

Part of the incentive for this exhibition and its narrow focus on the period of Suprematism, comes from loans from the collection of Nikolai Khardzhiev, a friend of Malevich and other artists, and scholar of the period. After efforts of some 20 years, he emigrated from Russia to Amsterdam in 1993. He took with him a collection of some 1,350 objects as well as countless documents. Paintings and drawings from his collection are included in this exhibition and are discussed in the catalogue essays.

In the 1920s, the artist was primarily involved in creating architektons, or maquettes for monuments and architecture. This exhibition includes a number of reconstructions based on photographs of exhibition installations. Few of the originals have survived. He also aspired to create pragmatic Suprematist designs for fabric and ceramics of which there are examples in this exhibition.

The great and largely incomplete history of the Russian avant-garde and its position in the art of the 20th century is still unfolding. Much of the work was lost, destroyed, or repressed. Artists, family members, collectors and museum officials preserved works often at great personal risk. It represents the dark side of how artistic revolution and radical conceptualism had difficulty coexisting with Marxist regimes. Ironically, artists often share the vision and ideals of the revolutionary philosophies that, in their pragmatic applications, tend to destroy them.

Ultimately, at least for me, this exhibition reveals Malevich as a radical thinker and conceptual artist. But as a painter, close inspection of the work itself, as compared to illustrations in books and magazines, is often disappointing. The application of paint is rather flat and generic. He did not appear to be particularly concerned with the material and its application. The paint is often thin and the edges not well defined. The works are not sensual to look at or as well crafted as works by such contemporaries as Kandinsky or Mondrian. A great Mondrian painting, for example, is always a magnificent object. This does not seem to be the case with Malevich. His paintings often seem more about the idea and composition than its execution. The paintings appear to illustrate theories rather than exist as objects in and of themselves. Perhaps this is why, in the 1920s, he was able to abandon painting, which he discussed in his writings, and then later return to it with some ambivalence and not great success.

Ultimately, there are aspects of Malevich that are stunning and remarkable as well as phases that are troubling. This exhibition lops off the bookends that bracket his greatest achievements. His earlier work as a cubo-futurist, was well represented in the National Gallery exhibition, as well as his late fumbles with figuration.

Based primarily on the remarkable works from 1913, particularly the campaigns of 1915, and the white on white works of 1918, Malevich surely belongs on the shortest list of the greatest artists of the early 20th century. This remarkable exhibition makes a compelling case for that inevitable conclusion.

-----