Alpine Landscapes and New Acquisitions on Paper at the Clark

The Clark's Fall Offerings

By: Michael Miller - Oct 26, 2006

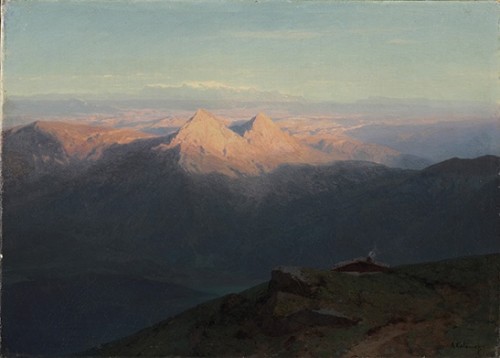

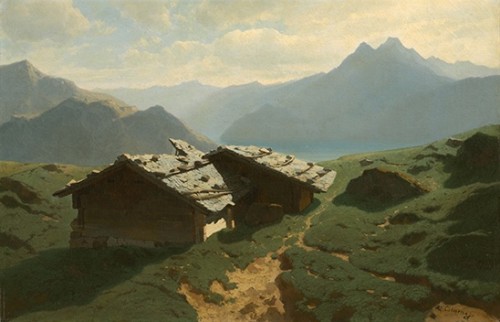

"I should be content if my portraits of the great Alps can make people say that the Heavens speak of the glory of God and that their breadth make known His handiwork. The Creator is alive in me, and, as everything is intimately intertwined in our nature, my work takes part to the service rendered by my soul to the Author of all beauty and all truth."—Alexandre Calame*As grandiloquent as it is, Calame's statement appears sincere, just as his work is sincerely founded in his Calvinistic devotion and inspired by its mystical intensity—a quality which raises it above its immediate purpose of providing views of fashionable touristic locations for wealthy aristocratic and haut-bourgeois visitors to Switzerland. In his own lifetime as today Calame enjoyed the reputation as the best of several Swiss painters who created these views of the their homeland for an international public. He rightly occupies the center of this selection of works from a private collection, that of Asbjorn R. Lunde, consisting mostly of oil sketches executed in the field by Calame and his predecessors, competitors, and followers.

The views, as explained in the catalogue essay by the curator of the exhibition, independent scholar Alberto de Andrès, originated in hand-tinted etchings and engravings of Swiss lakes and the Alps, which were orginally produced as a sort of antecedent of the post card, already in the eighteenth century. These were straightforward topographical views sold to foreign travellers as mementoes, or souvenirs (a term occurring often among Calame's titles) of their visits. Both these educated travellers and the artists saw in the Swiss landscape strong associations with scientific investigations (from geology to botany) as well as history and literature, not to mention Swiss nationalism and liberal politics. Scenes like the Rütli meadow and Lake Lucerne had stirring associations for both the Swiss and their foreign guests with Wilhelm Tell and the foundation of the Swiss Confederation. As de Andrés oberves, Albert Bierstadt, the German émigré to the United States, made a significant impression in his adoptive country with his view of Lake Lucerne now in the National Gallery in Washington. Beyond that, a visit to these impressive places was seen as an experience which at the very least could expand the consciousness of the traveller beyond its ordinary state, and, among the more sensitive and cultivated, induce a mystical communion with their Creator. This sentiment is perhaps more readily apparent in the work of Turner and Ruskin who underwent profound formative experiences in the Alps, but it is no less central to Calame's work, which may strike the contemporary viewer as either rhetorical or academic in comparison.

When I first caught sight of Calame's two large finished works in the exhibition (which were, rather strangely I thought, hung side by side, I immediately recalled the dramatic landscapes of Jacob van Ruisdael, especially a view of a "Waterfall with a Half-Timbered House and a Castle" in the Fogg Art Museum, indelibly engraved in my memory by many casual encounters as a student rushing to class through the galleries, or even a few concentrated moments of study. I was not surprised to find that painting illustrated in the catalogue as an example of the influences absorbed by Calame on his 1838 study trip to Holland. Furthermore Ruisdael is not only typical of Romantic taste in Dutch landscape, he is, according to de Andrès, typical of the taste of the Protestant collectors in Geneva, where Calame grew up.

Calame executed these dramatic finished works with their wind-strained firs and raging torrents on commission for patrons of high material and social stature. The patron could request the type of scene as well as the scenic elements he desired: specific locations, mountains, cliffs, rock, trees, torrents, lakes, etc. The artist spent his summers making field trips in various regions in spite of a bad leg and generally weak health, drawing and painting oil sketches of specific details of the landscape to be combined later in his studio for his clients. These fresh, sensitively observed sketches are what appeal most to Mr. Lunde, as well as to the rest of us today. What impresses most about these small works is the artist's immediacy of observation and his eye for the accidents and irregularities of nature in the warm, pure Alpine light. To lay these down on canvas or cardboard, Calame used a fluid brush and pigment, probably well diluted with oil, and his informal, unpretentious execution ranges from quite thin layers, which leave the ground visible, to a moderate, liquid impasto.

This sense of ocular experience in nature is by no means lacking in his predecessors Wolf and Töpffer or in his contemporaries, Menn, Steffan, et. al. On the other hand formal conventions rooted in the previous century also appear, not only in Töppfer but in Calame's older rival Diday, and even in Calame's own work, especially the earlier pieces.

An artist's rendering of space is one of the first things I look for, because, according to some art historians, it is a phenomenon peculiar to an artist's situation in time and space. A work by Dürer looks quite flat in comparison to a work by his Italian contemporaries Michelangelo or Raphael. This is not a question of ability or quality; it is rather a local characteristic, often determined to a certain extent by geographical and atmospheric conditions. I was stuck by the flatness of Calame's treatment of space. He seems to observe each element individually, proceeding upward in planes to the top—not an unexpected phenomenon in Switzerland, where one confronts so many vertical surfaces. I observed some communalities in the other artists, perhaps least of all in Steffan. After giving the matter some thought, I read in the catalogue that Calame lost one of his eyes in youth, and, to be sure, this is amply apparent in his work, not as a defect, but as a fascinating peculiarity not untypical of his environment.

The exhibition is thoroughly enjoyable, and, judging by the number of stimulated and engaged visitors in the gallery, it is not lost on the public. The groupings of the paintings by type encouraged the viewer to focus on aspects of Calame's working process, but it also resulted in the hanging of his two large, dramatic finished works side by side—which failed to do justice to them and hinted that the experience of two of three galleries full of Calame's finished landscapes might prove deadly. In spite of the conceptual presentation, the liveliness and variety of Calame's work came through brilliantly. Another reservation arises from the circumstance that all the works come from the same collection, and, if they have not all been cleaned by the same conservator, they have been cleaned for the same taste. Almost all, as far as I can remember, have been coated with the same liquid, glossy varnish, which, I fear, may conceal some of the peculiarities and variety of the painters' technique.

The catalogue consists of color reproductions of thirty-eight works, as well as a handlist, and a superb essay by the curator, which provides a most useful introduction to nineteenth century Swiss Landscape painting, a field which is all too unfamiliar to most of us today.

*

The Clark is concurrently offering a small exhibition of recent acquisitions on paper, including a typical, and rather fine pen and wash drawing of the Annunciation by Luca Cambiaso (Moneglia, Genoa, 1527 - Madrid 1585) and a group of interesting studies by Jacques Villon (France 1875 - 1963) of a bust of Baudelaire by his brother Marcel Duchamp-Villon (France 1876 - 1918). However, I'd like to point out a tiny pencil study by Adolf von Menzel (Breslau 1815 - Berlin 1905), which I especially enjoyed, a study of Baroque putti, details of a fountain at Nymphenburg. Menzel, who roamed all about Berlin and its environs with his sketching pad, here combines baroque ornament and line with his own sharp, quasi-photographic eye for light and form.

---

*Alberto de Andrés, Alpine Views, Alexandre Calame and the Swiss Landscape, exh. cat. 2006, Williamstown, Massachusetts, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, p. 43, no. 62. (The reviewer's translation.)