Lucio Fontana at the Guggenheim

Slash Art by Argentine/Italian artist

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 01, 2006

The special exhibition "Lucio Fontana: Venice/ New York" October 10 through January 21, 2007 at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which opened in Guggenheim Venice, is relatively small and confined to the galleries off the main spiral. But it is the most ambitious view of the artist (born 1899 Argentina died in Milan 1968) in New York since a Guggenheim retrospective in 1977. It was a stunning revelation for those who think they know the work from the few examples of slashed and punctured canvases on view in museum collections.

To view the work in depth is to come to grips with the great range and intensity embedded in what may initially seem to be a limited and formulaic approach. But within the rigid vocabulary of the conceptual approach to art making there is a great sensuality and variety to the individual works as well as the major Venice and New York series presented in depth here from the last years of the artist's life.

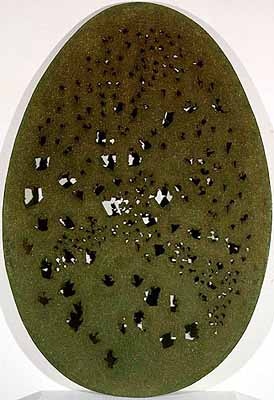

In 1961 the artist was invited by Paolo Marinotti, owner of the exhibition center of the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, along with Jean Dubuffet, Mark Rothko, Sam Francis and others to participate in the exhibition "Arte e Contemplazione." The artist was inspired by the city to create a series of works with thick paint applied to canvases with hands, fingers and simple tools that were then punctured and slashed. It was a particularly lyrical series with shimmering surfaces and textures which emulate the reflections of buildings in the lagoons. It was a triumphant series that he then brought to New York for his first exhibition there at Martha Jackson Gallery. When he traveled to attend the event he was in turn inspired by the canyons of Manhattan's sky scrapers which resulted, upon his return to Italy, in the New York works. These comprise large plates of copper and aluminum which have been slashed, punctured and scratched in his signature manner. Never having seen these metal pieces they were astonishing.

What is revealed by this exhibition which includes selections of the early work as well as these two culminating series is the impact of how well the oeuvre holds it own and continues to be remarkably fresh and insightful in the generation plus of developments of contemporary art since his death in 1968. His work holds because it is at once minimal and conceptual, particularly the flat, monochromatic canvases with several slashes, as well as richly gestural and even expressionist in built up surfaces conveying a love of the material and the implied energy and even violence of the hand slashing and puncturing the surface. There are parallels to the frenetic flinging of paint by Jackson Pollock or the movement and energy of the abstract expressionists. But what keeps his work more contemporary and less dated than theirs was his decision to confine and limit the works in terms of scale, restraint and a lack of excess in the implied emotion and violence of the "destructive" attacks on the canvas, metal or sculptural materials. Uniquely Fontana appears to have his cake and eat it too as arguably the only example of "Miminalist/ Expressionism."

There is far more to the long and complex career and impact of Fontana than is hinted at in this exhibition and resultant short review. He was involved in important avant-garde movements in Argentina and Italy and also created bodies of work that belong to the complex canon of art/ science and technology. This is beyond the scope of a brief review of the Guggenheim exhibition. But it is tantalizing enough to want to view and deal with the work in greater depth.

But the simple gesture of Fontana's slashes and punctures also provoke a range of responses from informed viewers. Just prior to visiting the exhibition I learned from art dealer Stefan Stux just how moved he had been when the work of Fontana was literally the first contemporary art he directly encountered when his family managed to leave Communist Romania first arriving in Rome before moving on to New York. The work became for him a powerful signifier of the very lack of freedom that he had endured growing up in a Communist regime that views all aspects of modernism as counter revolutionary and inappropriate to the mandate that Marxist art should confine itself to agit-prop. For Stux the Fontana works were a surrogate for freedom.

On the other hand, several years ago, during a trip to New York with an artist friend who makes representational paintings which I respect, he pointed to the slashed canvases of Fontana as a surrogate of all that is wrong with contemporary art. The very word Fontana, in our subsequent debates, became for him a paradigm of the absurdity of the avant-garde. The artist spends time each year in Italy looking at "true" art. It is an impossible argument and I have just agreed to disagree. But seeing this work at the Guggenheim was also an opportunity to field test assumptions. Am I just a "knee jerk" avant-gardist in defending and praising the work of Fontana? This experience was a rich and resonating affirmation of the original instinct. More than just a visual experience viewing this work was deeply personal and emotional. But also with a certain caveat that such responses do not come quickly and easily. They result from years of looking. Here the depth and quality, the commitment and passion of the work is readily evident. That said, why is the mood so apathetic when viewing the majority of contemporary work in rounds of New York galleries? The challenge is how to get it right the first time and trust your basic instinct. The first time I encountered work by Fontana decades ago it was puzzling but fascinating. It seemed important if also absurd. And it has taken all this time to balance the equation that yes, indeed, it is more important than absurd.