Bulrusher

Relationships and Mysticism in the California Redwoods

By: Victor Cordell - Nov 03, 2023

According to this story, Boonville, California, 20 miles inland from the town of Mendocino, was never recognized for its diversity. Prior to World War II, a lumber mill had attracted some black laborers, but it closed, and by the early ‘50s, a single black man named Lucas remained.

However, a somewhat mystical addition appeared 18 years earlier. Found in a basket in the river reeds was a newborn Black girl. She would be raised by a white man called Schoolch, which in the surprisingly extensive Boonville patois meant schoolteacher. The girl was given the name Bulrusher, which was the generic for foundling or illegitimate child. Not only was she racially unique among her schoolmates, but she possessed a special trait. She could read water – seeing the future of a person who touched the water. Of course, not all were happy to hear what was to come.

If the whole milieu of “Bulrusher” seems off-kilter, the characters we meet seem even more eccentric than you might expect. To begin with, the charming title character reveals rich and eloquent sentiments, but she has never had a friend. Various explanations as to why she is a loner are advanced by those around her, and they don’t relate to race. It’s because she doesn’t “harp the ling” (speak like other locals do), or because she doesn’t have known blood family, or because her special gift makes her weird.

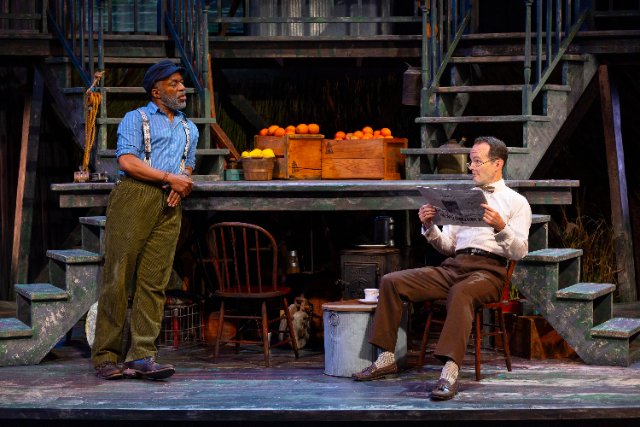

Most of the action takes place in the public area of a brothel, which is certainly a surprise enterprise in a small California town. Schoolch, who is also a loner, hangs out there drinking tea but doesn’t partake of the carnal offerings. Lucas frequents the house but does enjoy the sex and also has emotional and physical history with Madame. Both men have a crush on her.

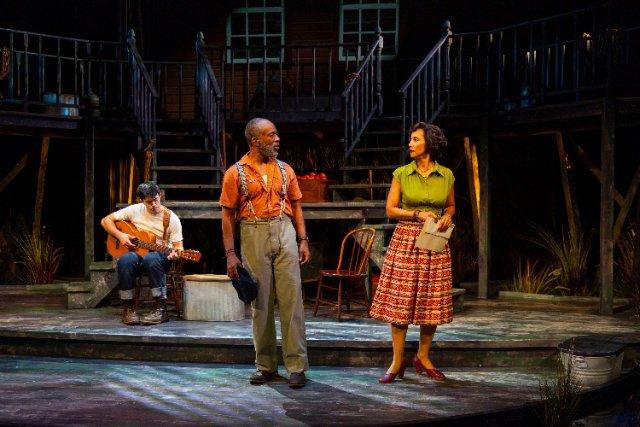

It is not clear where this play is going, but it receives more shape upon the arrival of Lucas’s previously unmet niece, Vera, who has come from Alabama unannounced. She is taken aback by local practices such as her being served in a café by a white woman. Her presence acts as a catalyst to events and also underscores differences in racial relations between former slave states and those that had less experience with the tragedy of that institution. It also points up an interesting sociological dynamic. In situations where minorities are scarce and don’t seem likely to grow appreciably, minorities tend to be treated amicably and as a curiosity. It is when their numbers surge and begin to represent a threat that the majority population tends to negatively react to their presence.

Vera’s experience and friendship become an education to Bulrusher who had been unfamiliar with things like Jet magazine and modern lynching. She hadn’t even seen another black woman, and part of her allure is her growing through learning. Another issue surfaces from outside of Bulrusher’s experience, and that is why blacks stay in places they hate where they continue to face oppression. Vera’s explanation is that they are tired of running. Thus, many will courageously stay in the South and stake their claim despite the risk and hardship.

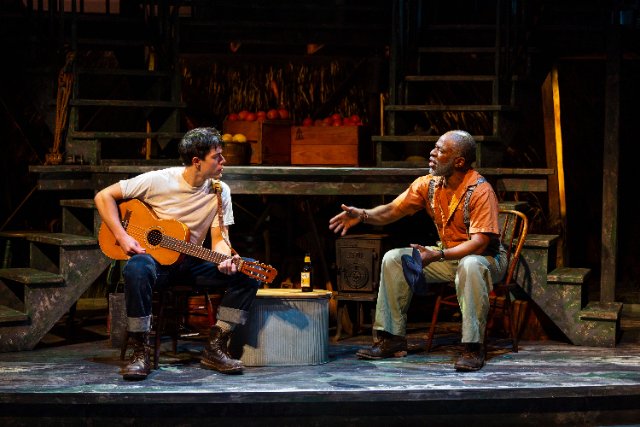

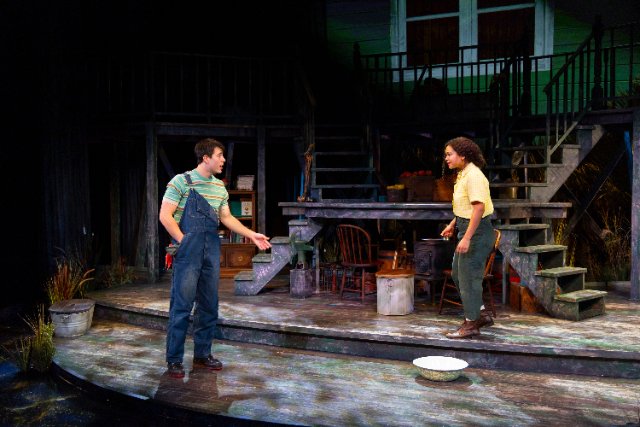

Playwright Eisa Davis has crafted a highly appealing play that covers a lot of ground. It deals with race, sexuality, home, family, and the sense of belonging. Connections between some of her characters sometimes clash, but that is reality. The narrative is offered from the black perspective, but rather than a strident view of race relations, it comes across with greater hope of how things can be. While clashes abound, they’re not about race. Two complicated attempts at interracial romance are replete with differences. But in one, Boy, who loves and chases after Bulrusher, seems oblivious to the fact that she is of a different race.

Overall, the characters are nuanced and somewhat empathetic. Schoolch is perhaps the least engaging personality, but how can you not appreciate that he as a single man raised a foundling?

The exception is Madame, who is as rigid as a metal post. A disciplined workaholic who looks more like a school principal than a brothel owner, Madame has her own sense of morality and wants her world to consist of straight lines. She knows that because of her line of work, she won’t receive any invitations to the Apple Festival, which suggests why she sublimates social involvement with business that she can control. Although others have baggage as well, she has more, and she keeps her secrets hidden by maintaining social distance. After previous false starts, Madame does have the opportunity to sell her property at a good price and move on. But the question is whether, like black people who choose to stay in Alabama, she feels that she is home.

Relationships reflect various dynamics. Boy and Lucas are both persistent in their romantic forays despite headwinds from their intendeds. Bulrusher and Vera’s affinity becomes complicated. The one affiliation that doesn’t resonate is between Bulrusher and Schoolch. It just doesn’t seem like a family connection, with no explanation as to why they don’t act like father and daughter. Bulrusher even calls him by his familiar name, which would have been unheard of in the early ‘50s.

In the end, some matters are clarified, while others are unresolved. That’s life.

The creative side of Berkeley Rep’s co-production, directed by Nicole A. Watson excels. Although relying on a single set does create some location confusion, it ably depicts the redwoods environment that it represents, enhanced by superior lighting, sound, and extensive projections. Acting also is solid. Jeorge Bennett Watson is smiling and charismatic as the black-poetry quoting Lucas, and Shyla Lefner is austere and businesslike as the incongruous Madame. Jordan Tyson as Bulrusher has a demanding role with a ton of dialogue, and she does capture the character’s youth and inner conflicts. While she enthralls most of the time, she is not fully convincing on occasion, especially in the dénouement.

“Bulrusher,” written by Eisa Davis, is co-produced by Berkeley Repertory Theatre and McCarter Theatre Company and plays on Berkeley Rep’s Peet’s Stage, 2025 Addison Street, Berkeley, CA through December 3, 2023.