Edward Hopper Shown in the Berkshires

Gregory Crewdson responds to Hopper in Williams College exhibition

By: Jane Hudson - Nov 05, 2006

"Drawing on Hopper: Gregory Crewdson/Edward Hopper," Williams College Museum of Art, October 12, 2006–April 15, 2007

As part of a continuing series of curatorial experiments entitled "Encounters" Williams College Museum has invited photographer Gregory Crewdson to respond to Edward Hopper's painting "Morning in a City" which is part of the permanent collection of the Museum and a Bequest of Lawrence H. Bloedel Class of 1923. In addition to the painting there are nine studies for the painting, which elucidate the artist's compositional process.

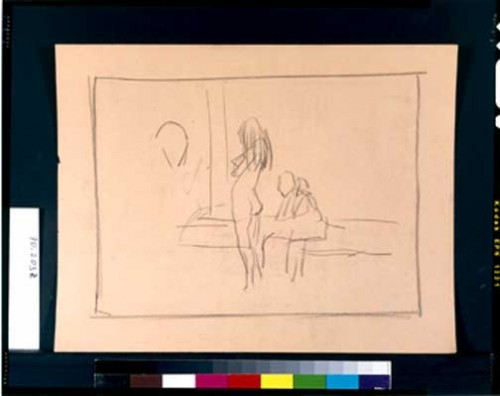

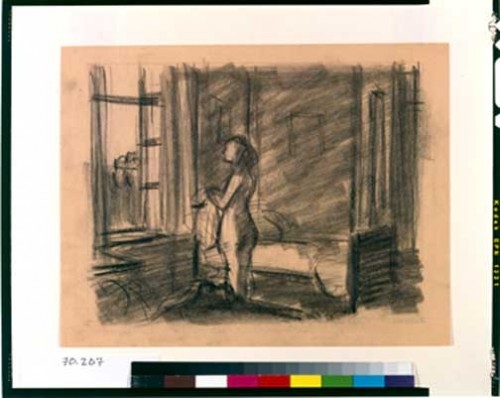

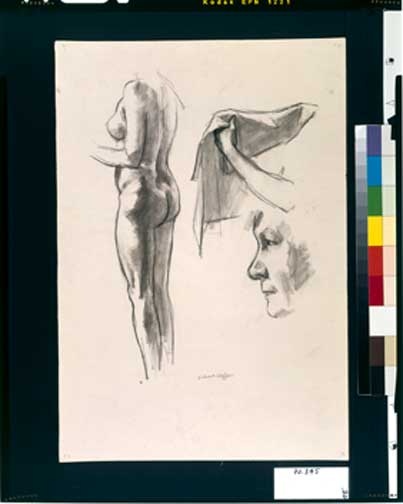

Gregory Crewdson presents three large digital c-prints completed in recent years, He also includes a few smaller works documenting the extensive production process of his compositions. Initially one cannot help but be struck by the difference in scale within which these artists frame their visuality. Hopper operates as a solo artist, wherein the entire process is directed by his physical gesture. His model is his only mirror, as it were, and she (his wife, Jo Nivison) serves as a cipher for the evolving image of 'woman' to which he eventually commits (see the studies). Crewdson, on the other hand, depends on a production mechanism akin to that of cinema where actors and technicians are directed toward a fictional 'scene' of operatic complexity and scale.

Both Hopper in his time, and Crewdson in his are responding to the psychological ground of the American psyche as it was/ is presented in film. There is a drama to the alienation/ reduction in Hopper where the lonely muse is isolated in the glare of urban light. One thinks of the dramas of the 30's (Stella Dallas) where women have been forced to enter the marketplace and were stripped of their safety net, exposed and naked. In the Crewdson light, a harsh, digital simulation fills in all information, revealing all details of a constructed bathos. This appeal to the profound failure of selfhood (think "Twin Peaks" without the Log Lady) as seen in the overwhelming distances between subjects and the object world is seductive in its lush attention, but leaves an artificial aftertaste and a question for the art object as to its capacity for insight. One thinks of Walter Benjamin's post-authentic object as a product of the mechanics of reproduction ("The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction") wherein what was traceable to an originary moment, is sacrificed for the sake of a ubiquity, a closeness, a shrinking of the privileged distances of the world.

Chrissie Iles, Whitney Museum of American Art curator suggests in a video that accompanies the show ("art in progress: Gregory Crewdson," produced, edited, and directed by Ben Shapiro, Gallery HD, copyright 2004) that Crewdson takes on the "mechanics of cinema producing an uncanny, sophisticated, and psychological power" (his father was a psychologist on whom he spied as a child). He came of age during the 90's when there was a shift toward the psychological in art, and consequently explores what lurks beneath the perfect façade of the American vernacular.

We see in Hopper a reduction of environmental details reaching for an essential isolation. In the painting, "Morning in the City" (recently restored at the Williamstown Conservation Center), the figure of a nude woman stands in the light shining through a window which reveals nearby buildings, and the urban setting of the scene. She holds a towel, may have just arisen from the mussed bed, or just bathed. Her clothes, including a hat, rest on a chair nearby suggesting the impermanence of her presence. In the preparatory drawings for the work, only one depicts a male figure seated on the bed (the artist having thought better of the suggestion of a sexual resolution to the narrative) [70-sm.jpg]. Here this woman is unhinged from a ground of belonging and stands poised to assume the risk of being modern. The alienation of her relation to the world is a function of the loss of detail, the removal of all things personal and anecdotal, ancestral and domestic. All that remains of the natural from which she has been plucked is the light of the sun which falls somewhat weakly across the architecture of the room and her body. She might as well be furniture for all of her immanence as a muse.

In Crewdson's "Untitled (Beneath the Roses)" 2005, a nude woman-of-a-certain-age stands in the bathroom, in the middle of a hotel room, her clothes strewn on the floor, hung haphazardly over chairs, while she stares into space with little or no affect, grey of visage and general skin tone, and bleeding from her vagina. Has she been raped, has she just begun to menstruate even though her reproductive years seem to be past, is she suicidal? Something has happened in this room where the key is thrown onto the still-made bed. In this image, as in the Hopper, the woman is the psychological container for the narrative impact of the image. Her place in society, her accomplishments and disappointments, her history all hang on her bones as an awkward second skin.

It is often the case that Crewdson's characters seem to be weighed down by their very physicality. They occupy space with anxiety as if they would have preferred to exist as virtual entities or not at all. He plays with the atmospheres of the 'real' creating vast distances into which he thrusts his players. His 'mis-en-scene', crafted through agonizing attention to detail in sets, costumes and most especially lighting, surpasses a naturalist rendering of the real and takes on the surreal energy of dreams. He directs his production crew with the strictest intentionality, shooting images during the elapsed time of the emotionally charged gestures of his narrative. What emerges as the final print is an amalgam of portions of the image that 'work' and that are then cobbled together digitally to produce the facticity he intends.

In another piece on this site ("Rape of the Sabines", 10/16./06) I offered a response to Eve Sussman's operatic-scale video production based on "The Intervention of the Sabine Women" by Jacques-Louis David. With a similar reliance on the fullness of detail, the over-whelming 'presence' of everything, Sussman also attempts to concentrate enough energy to transcend the flat ubiquity of technologically framed imagery, and to yield something of the dramatic power of classical confrontations. Her work also pretends a kind of profundity, a spiritual revelation through the 'look' of theatrical/filmic bravura. But we are left with more of a sense of the cachet of the devices, the apparatus, than any kind of satisfying empathic creation.

In making the comparison between Hopper's pared-down and personal analytic and Crewdson's 'tours de force', one has to consider the consequence of the inflation that makes 'big' works like this come into being.

Born in 1962 in Park Slope, Brooklyn, Gregory Crewdson studied photography at the State University of New York at Purchase and received his Master in Fine Arts from Yale University. He has taught at Sarah Lawrence College, Cooper Union, Vassar College, and Yale University. He is represented in New York by Luhring Augustine Gallery and in London by the White Cube Gallery.

(Courtesy of Williams College Museum of Art, http://www.wcma.org