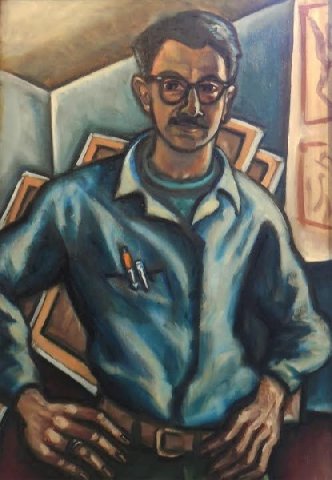

Arnold Trachtman Boston Protest Artist at 89

A Formidable Legacy of Social Concern

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 09, 2019

With an epic commitment to social justice Arnold Trachtman was an unique and underappreciated monument among Boston artists of his generation. He was born in blue collar Lynn in 1930 and passed on November 7 in Cambridge. In the 1970s he and Joan bought a house on Dana Street where they raised Maxima.

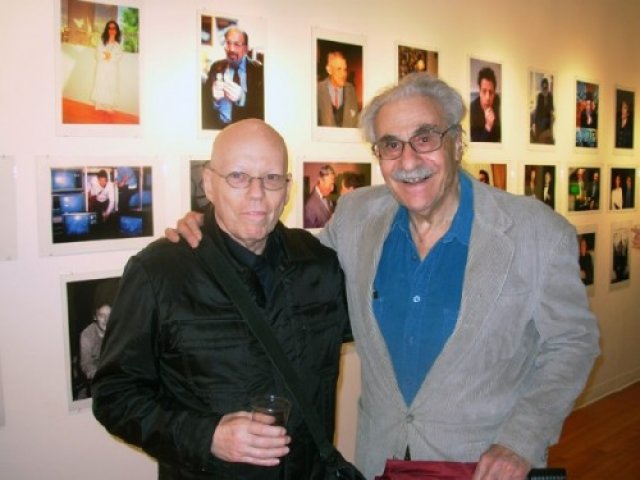

We met during the Vietnam protest years and on a few occasions showed together. Whenever possible I curated his work in thematic shows and reviewed his exhibitions.

An exhibition of his work at a Harvard dormitory was censored and closed by the University. Through a relationship with then director Drew Hyde we moved the show to the Institute of Contemporary Art on Soldier’s field road. That project initiated a professional and personal relationship.

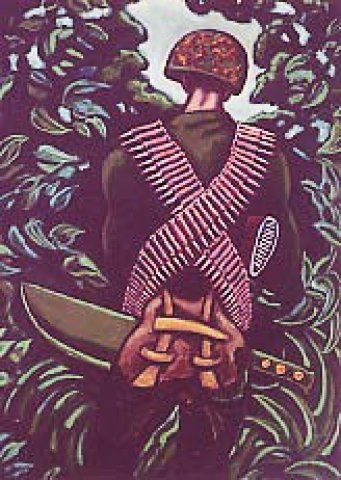

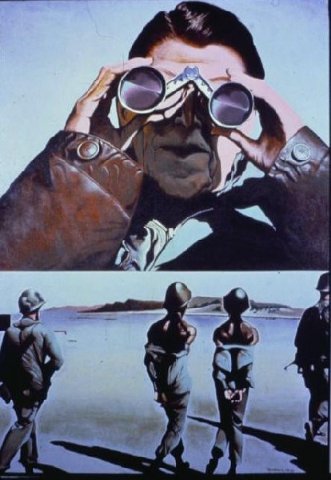

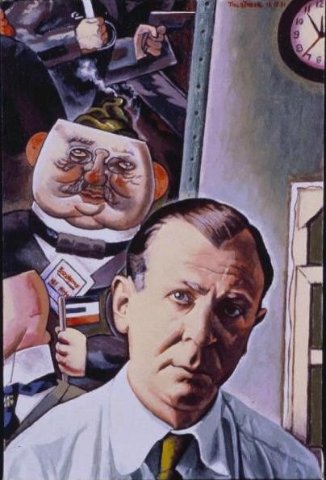

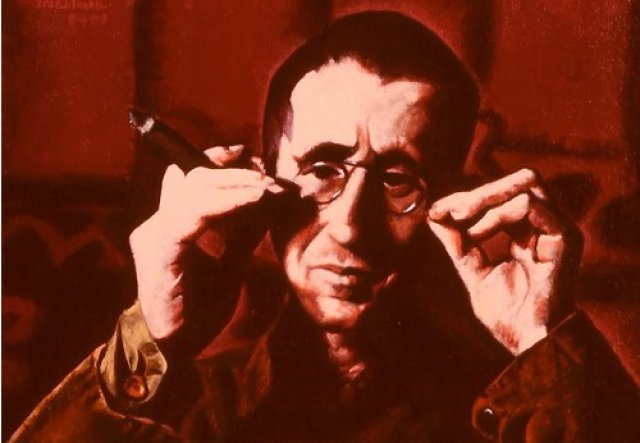

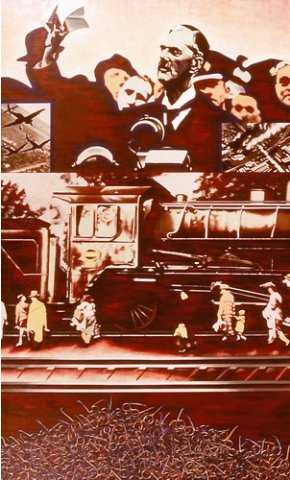

"I was born in the United States, three years before the Nazis came to power in Germany. I was lucky. I grew up in the 'Arsenal of Democracy.' And yet it was not always safe. Anti-Semitism thrived here. At any time you could be attacked, verbally, physically or both, by kids your own age or older, and sometimes by adults. The end of the war came with newsreels of the camps and the infinite mounds of the dead being bulldozed into great pits. The survivors looked just barely alive. Their pain was palpable. When I found my direction as an artist, I made work about issues of the day. While pursuing these themes, I found myself continuously drawn to the history of Nazism. Yet it did not appear in my work. I wasn’t ready. In late 1985, I was. What I wished to do was demystify the demonology of Nazism. I wanted to show the men behind this great engine of genocide: the major industrialists and corporations of Germany, such as Thyssen, Krupp, Daimler, Benz, Siemens, to name a few. Ten years after the war, all of them were back in business. Understanding the epoch of Nazism, economically, politically, and socially, is part of the unfinished business of our era. As this century draws to a close, aspects of Nazism are manifesting themselves in various parts of the world. We must penetrate the darkness of our past in order to have a future." Arnold Trachtman

The dominant style of art from the 1930s through the 1960s was Boston Expressionism. In particular one might note a connection to the satirical work of Jack Levine. But after the war, and a stint in the Army, Levine moved to New York. The Boston Expressionists were primarily associated with The Museum School and Boston University School of Fine Arts under David Aronson.

As a graduate of Mass College of Art, then primarily mandated to prepare high school art teachers, Trachtman found his style and subject matter independently. In later years he was an adjunct professor at Mass Art. He was also for a time a high school teacher. That’s where he taught Marjorie Kaye. While formerly director of the cooperative Galatea Gallery in the South End she curated several solo shows.

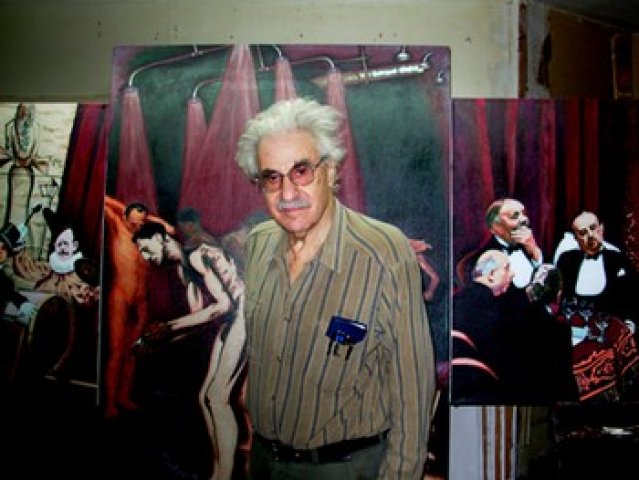

When we met in the late 1960s he told me about losing most of his early work. There was a fire and while walking home he saw his work in flames being thrown out of the studio window. Early on Mark Favermann, then the director of the Boston Visual Artists Union, and I met as dinner guests. We have both continued to write about him often for this site. After dinner we visited the generally cluttered studio. He was a prolific artist trying to keep up with the news cycle.

After the Vietnam War he turned to depicting the Nazi era and global injustice. Taking a break he would make occasional still life and landscape paintings. In particular Mark and I loved his “portraits” of musical instruments. I included one in a show for the Boston Visual Artists Union Gallery. It was organized to highlight the annual Boston Globe Jazz Festival.

The still life and landscape paintings were marketable and we encouraged Arnie to focus on that direction. Typically, he bristled at the suggestion and remained committed to social justice work.

Those paintings were included in museum exhibitions and traveling shows. The Decordova Museum purchased a major work from a group show. Not surprisingly Trachtman was ignored by the Museum of Fine Arts. By comparison, under curator Barry Gaither, the MFA has shown and owns work by the similarly oriented African American artist Dana Chandler, Jr. They are often compared, knew and respected each other. Another egregiously neglected leader of that generation was visionary artist Paul Laffoley. These three artists represent a niche or subculture outside the mainstream of the Boston art world. It would be nice to think that one day the MFA will come to its senses. As it has recently recognizing Hyman Bloom after decades of neglect.

Trachtman, however, had champions and allies. The former Nasrudin Gallery showed the work as did, more recently, Galataea and Childs Gallery. The late keeper of prints and drawings, Sinclair Hitchings, acquired some 60 works on paper for the Boston Public Library. Hastings gave Trachtman a major retrospective. Former Boston University professor, Patricia Hills, whenever possible curated and wrote about his work.

There was a small and deeply committed cabal of “Friends of Tracthman.” The artist, however, was not interested in or adept at self promotion. He never adapted to computers and accordingly didn’t see or take interest in our on line coverage. When asked about that during a phone call he commented that he relied on Maxima for information.

Through FOT we learned of poor health in recent years. That meant that he largely missed the Trump era. At the height of his career it would have been red meat for his carnivorous paintings. One might readily imagine The Donald as a ranting and raving Orange Julius in his work.

One would like to imagine a new generation of vibrant protest artists. There is much to be concerned about. But art wise, sad to say, looking about it appears to be all quiet on the western front. That’s all the more reason to note the passing of a remarkable socialist carnivore.