Jack Levine at 95

Leading Boston Expressionist

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 10, 2010

Jack Levine a legendary political polemicist in paint has died at 95. Since being mustered out of the Army, after serving in WWII, he lived as an exile from his beloved Boston Red Sox. As a New Yorker it is fair to say that Levine never embraced the Yankees.

What a mensch. Mazeltov, Jack.

I knew him well. Loved the guy and his crusty wit. He was known to hate critics. But we got along just fine.

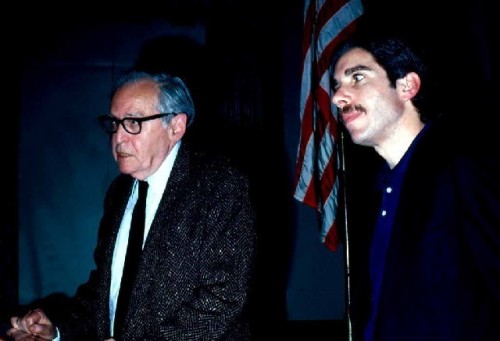

When David and Nancy Sutherland were making art documentaries in the 1980s I hung out with them and Jack. Previously, they had done a film on Paul Cadmus. There wasn’t much fame or glory in making well crafted, low budget films about artists. Particularly guys like Levine and Cadmus who, decades before, had fallen off the art world radar screen.

The Sutherlands later became well known for their PBS documentaries The Farmer’s Wife (six hours, 1995) and Country Boys (2006). They split up while shooting the latter project. I have tried to contact David several times with no response.

While I was an art major at Brandeis, my professor, Mitch Siporin, invited Jack to give a slide lecture on his work. It had a profound influence, and, for a time, I painted ersatz Levines. One was a large work with glazes that depicted a gathering of politicians with a stripper popping out of a huge wedding cake. It disappeared long ago but may pop up on eBay.

This week, we anticipate the grand opening of the Art of the Americas wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. We will learn what place Levine, and his boyhood pal, Hyman Bloom, have in the telling of the history of Boston artists. Will the story line that starts withSmibert, Feke and Copley through Sargent, and the Brahmin Impressionists, fizzle or slow to a trickle when, during the Depression and post war era, the leading artists were immigrants and Jews. In addition to a few works by Levine and Bloom, will we see the third Boston Expressionist, Karl Zerbe, and their progeny? Will the MFA even remember that Kahlil Gibran lived in the South End and made visionary art?

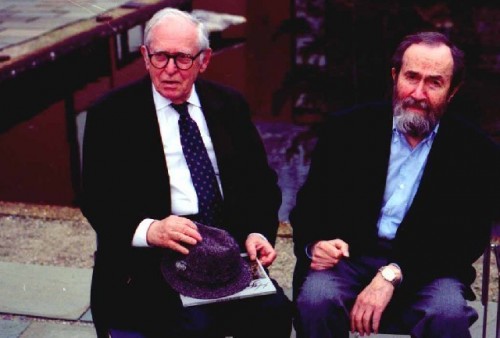

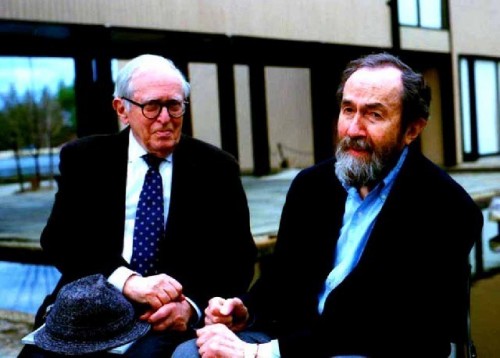

We will know the answers to those questions in a matter of days. But I’m not holding my breath. Since Bloom’s death,in 2009, there has been some effort to rehabilitate his reputation. The Danforth Museum has advanced his cause. Some years ago, when it still showed art, the Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton mounted a Bloom retrospective. Jack came to the opening and I photographed them together. They had kept in touch but didn’t see each other very often.

As a mystical visionary and painter of expressionist Rabbis, as well as harrowing cadavers, Bloom is ripe for reappraisal. He was even briefly admired by Clement Greenberg as a precursor of Abstract Expressionism. A new generation of revisionists are willing to take a look at Bloom.

But nobody is going to bat for Jack.

Even though, back in the day, he painted works like “Gangster’s Funeral” “ Feast of Pure Reason” and “Welcome Home” that defined an era. They are icons of the social and political zeitgeist. It is the norm of contemporary critics and art historians, however, to dismiss all work with an agit-prop agenda as “cartoonish” and as dated as yesterday’s newspapers.

Levine, however, who continued to create topical art long after critics ceased to pay attention, saw himself in the tradition of Titian, Velasquez and Rembrandt, for their subject matter and handling of paint, the harrowing fury of Goya, the political wit of Daumier, or the acerbic irony of George Grosz.

It amused him that he achieved more infamy than fame. There was a flap when his work was included in post war exhibitions of American art organized by the State Department. One of his painting “Welcome Home,” which depicted a general as an honored guest at a decadent banquet, caused a media controversy when it was shown in Moscow. Ike, then president, refused to censor the show commenting “It looks more like a lampoon than art as far as I’m concerned.”

Ike may not have known much about art but he hit the nail on the head with that “lampoon” observation. Like the Social Realists of the 1930s, Levine, and all political commentators, of the 20th century in America, have been dismissed by post modern theorists and critics.

Well, except for us old moles who still love a good picture. In that sense, Levine was a really terrific painter. On every level, he was on a par with the now more widely admired Bloom. They were cut from the same cloth but Jack just went for a different tailor.

If you went back to their roots Jack and Hyman were hatched as Castor and Pollux.

They were kids taking art classes at the Jewish Settlement House in the South End. Their teacher was Harold Zimmerman from the Museum School. He spotted their talent and took them to Denman Ross a professor at Harvard. From there Ross tutored them and gave them a stipend.

Mostly Ross emphasized creating from memory and imagination. He also introduced them to the theory of Dynamic Symmetry by Jay Hambridge and golden section compositions.

Ross acquired an extensive stash of their juvenile drawings which he gave to the Fogg Art Museum. With Jack and the Sutherlands we visited the drawings room of the Fogg. Jack had a conversation with his long time friend, curator Agnes Mongan.

Looking through the drawings we came on a lovely rendering of a cello player. When asked about it, Jack commented that Ross sent them to the BSO, and asked them to draw the musicians from memory. It was remarkable for its sensitivity and detail. There was also a drawing that revealed the many vectors of a Hambridge analysis of space. Jack didn’t have much to say about it other than as an exercise assigned by Ross.

After the Fogg visit Jack joked that he and Hyman thought of themselves as Harvard grads but without the degree. That extensive collection of drawings would make a great exhibition for the Fogg. Or a loan to the MFA for a long overdue exhibition of that pair of seminal Boston painters.

During the 1930s Levine got a stipend through the easel program of the WPA. To get their relief checks artists gave paintings. When the program was disbanded museums were allowed to acquire what they wanted. The rest was sold as scrap. In New York, WPA paintings were used to cover pipes in public buildings. Or sold by the pound on Canal Street. Many of the WPA murals were painted over. Some later to be rediscovered like Gorky’s for the Newark Airport.

An icon of American art Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” in the Art Institute of Chicago, is a WPA painting. That’s how Levine’s popular “String Quartet” ended up at the Met as well as other works in museums including the MFA.

It’s just as well that Levine split for NY after the war. There was nothing happening in Boston. It would remain pretty dead until the late 1960s and the revival of the ICA under Drew Hyde. He pulled a Lazarus for the then deceased Institute. The ICA then fought the good fight under David Ross and beyond.

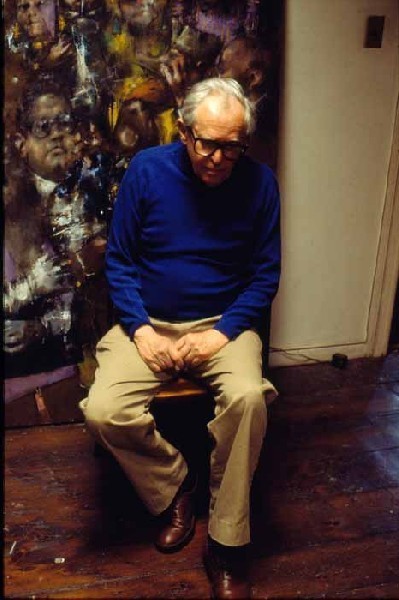

Jack had a better shot in NY. It’s where his wife, the painter, Ruth Gikow (1915-1982), insisted they live. When I visited Jack’s home and studio with the Sutherlands there were works by her hanging in the halls.

Long after he was out of fashion Levine continued to make great paintings. Sutherland particularly loved “Orpheus in Vegas.” What a picture. It was an update from his 1930s gangster paintings taking on Sinatra and the Mafia in the 1980s.

I don’t know about the Biblical stuff like “David and Goliath” or “Cain and Abel” which was acquired by the Vatican in 1975. Of that work Levine, a secular Jew, commented that “I came by that subject matter honestly.” They are more satiric and ironic than Bloom’s often mordantly cloying rabbis.

We live in an era that cries out for the wit and insight of a great satirist like Levine. It is fertile ground for comedy. But, in general, all aspects of narrative and commentary have been leached out of the fine arts. Social and political art is just so uncool. Unless it is Kara Walker deconstructing “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Content in art today has to be ironic, layered in obfuscation, anointed by theory. The art of Levine was shoot from the hip, take no prisoners, in your face, layered with the craft of Old Masters, and flat out, full tilt boogie. How rollicking retro and unhip. Exactly.

Jack Levine interview with Greg Cook