David Mamet Plays the Race Card

James Spader at NY's Barrymore Theater

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 07, 2009

RaceWritten and directed by David Mamet

Sets by Santo Loquasto; costumes by Tom Broecker; Lighting by Brian MacDevitt; Production stage manager, Matthew Silver; Technical supervisor, Hudson Theatrical Associates; Company manager, Bruce Klinger; Associate producer, Jeremy Scott Blaustein; General manager, Richards/Climan Inc. Presented by Jeffrey Richards, Jerry Frankel Jam Theatricals, JK Productions, Peggy Hill and Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz, Scott M. Delman, Terry Allen Kramer/James L. Nederlander, Swinsky Deitch, Bat-Barry Productions, Ronald Frankel, James Fuld Jr., Kathleen K. Johnson, Terry Schnuck, the Weinstein Company, Marc Frankel and Jay and Cindy Gutterman/Stewart Mercer. At the Ethel Barrymore Theater, 243 West 47th Street, Manhattan; (212) 239-6200. Running time: 1 hour 40 minutes.

Cast: James Spader (Jack Lawson), David Alan Grier (Henry Brown), Kerry Washington (Susan) and Richard Thomas (Charles Strickland).

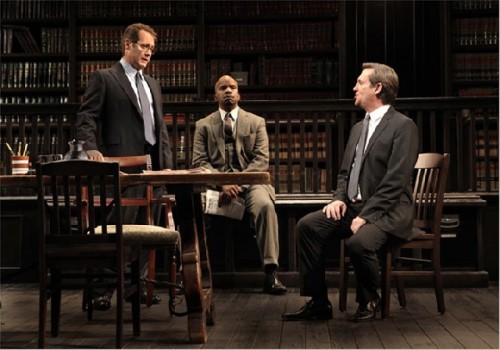

Yet again, in David Mamet's new play "Race," which is now at the Ethel Barrymore Theater on Broadway, James Spader is suited up as a smart, smarmy, cynical and arrogant trial lawyer, Jack Lawson. Here he is partnered not with mad cow Denny Crane (William Shatner) his cigar smoking, brandy snifting, womanizing, side kick on "Boston Legal" but rather with a tough, shrewd, and combative African American attorney, Henry Brown (David Alan Grier).

For some 20 years they have run a small but successful law firm. In the practice of criminal law it is all about winning. But the partners are conflicted about taking on what could be a no win case.

The potential client is a philandering billionaire who is accused of raping a black woman. He pleads his innocence and sincerely wants them to believe him. Charles Strickland (Richard Thomas) is a privileged fool who wants to take his case to the media.

It seems he has come to the partners having been turned away by a Jewish law firm. They want to know why and put through a call seeking disclosure as a professional courtesy. It seems there has been discovery through witnesses and evidence that makes the case tough if not impossible to win.

There is no question that the potential client can afford a defense but whether he deserves one is another matter. If they win there is financial gain. But the stigma of getting a rich white man acquitted for raping a black woman comes with collateral damage. If they lose potential clients will conclude that they can't win the tough cases.

It is also clear that the accused has deliberately chosen the firm for its racial diversity. Being defended by a black attorney will obviously strengthen his chances in court. But as Mamet argues through his characters times have changed. A generation ago, the accused would likely walk. As did O.J. Simpson in a controversial decision that was applauded by many blacks. But in the matter of this alleged crime, though Strickland is accused of rape, the real crime is racism. For which there is no adequate defense.

While the partners research and deliberate taking on the case an attractive, young, black associate Susan (Kerry Washington) hovers in the background. In the initial stages of the play she just listens . She is a study in elegant, understated control. Eventually she is drawn in as Jack assigns her tasks. These she executes with more resentment and attitude than enthusiasm.

Jack asks her questions about the accused. Does she think he is guilty? Her response is to ask him if he is asking her as an attorney, woman, or as a black woman? Ah, there's the rub. It opens up the discussion to race. Jack, the mouthpiece for Mamet, states that there is essentially nothing a white man can say about a black man that will be credible.

In that supercilious Alan Shore manner Jack declares that all people are stupid. Including black people Susan wants to know? Yes, he responds, even black people. He sees no reason why they should get a pass. He has other notions about the survivor guilt of Jews and what he sees as the sense of shame of blacks over slavery. This is delivered not so much to present him as a racist but rather as a smart attorney looking for leverage to work a jury in defense of a client.

Henry is more pragmatic stating to Jack "Don't call me brother." They are partners because it is about winning and money. As Jack puts it "I didn't like being poor." They don't have to like the client, or even believe in his innocence, they just have to defend him. For a fee. Susan sees it more in terms of justice. It is her attitude and sense of political and social entitlement that will prove to unravel the case and ultimately threaten to bring down the firm.

Mamet doesn't explain how Jack and Henry came to be partners. Their relationship and chemistry is never really explored. It is obvious that Jack is the star and brains of the firm but just what is Henry's role? Is their partnership the result of conviction or just convenience? They are successful but we don't quite understand why.

We came to the theatre with the hope and expectation of seeing Mamet, one of the toughest and most challenging playwrights of his generation, taking on yet another hot button issue. One expected the tough talk and foul language. In this production doled out in seeming moderation compared to most of his other plays.

Here the play suffers and may ultimately fail because even Mamet has been intimidated by his provocative subject. There is just too much vulnerability and exposure couched in a white, Jewish playwright taking on the taboo of race It is proclaimed in the very title of the play. What we get is way too muddled, fudged, and liberalized. You sense that Mamet was never sure about what he was after. Through sheer chutzpah he slogged on anyway. Perhaps he has gone to the well too many times.

There is, as usual, a brilliant and compelling script. Even on an off day Mamet is still, well, Mamet. The flashes of genius are so sharp and lightning bolt slick that we want to put the drama on pause, rewind, and play scenes again and again. This is a play that demands to be read, studied, and deconstructed. We want to hold the text in our hands and read it at our leisure. Or see this play several times. At $125 for an orchestra seat that is prohibitive for most of us.

While there are wonderful lines and compelling vignettes the whole of the play is less than its parts. This is exacerbated by the fact that the characters are drawn unevenly. Jack, the surrogate for Mamet, gets all the best lines. Henry, while tough, earthy and compelling is not the star and strategist of the firm. It is reported that Mamet hoped to cast Chris Rock in the role. Perhaps he was wise to decline as Mamet never really got into the head of the character.

The accused, Charles, is a fool, the more so as the plot evolves. There is nothing sympathetic about him. Not a shred of redeeming character to make him even vaguely sympathetic. He is simply an oppressor and womanizer with a taste for attractive black women. In this instance he didn't appear to take no as really meaning no.

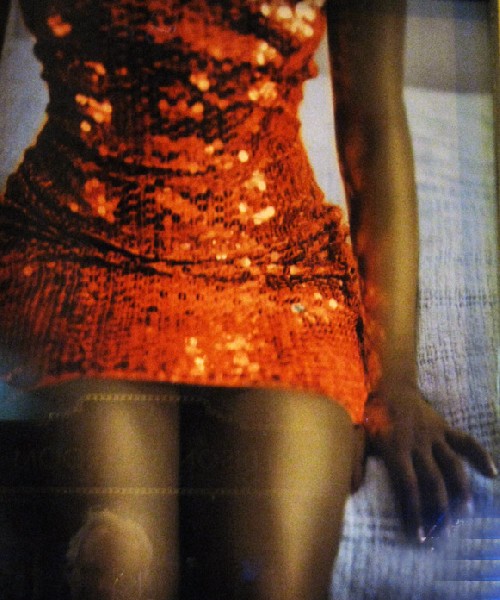

There is some back story that the victim was a long term mistress and the sex was rough but consensual. Jack devises a strategy to make that point through evidence. In this instance a sequined dress that he was alleged to have torn off of her. Were this the case then where are the sequins that would be strewn all over the hotel room? The initial crime scene reports failed to mention any sequins. This is to be the top secret defense. Jack will reconstruct the dress and Susan, who like the victim is black, young, attractive, and a size two, will wear the dress during a courtroom reenactment. The jury will have no option but to acquit.

The curtain came down on the first act way too quickly. On my watch it was just a half hour. The second act in two scenes flew by. For a lot of money it seemed like a brief evening of what one might see for free on TV. Was this just a night out for fans who miss Spader in Boston Legal? If so, where was Denny Crane?

In many ways Spader is still acting for the camera. From seats in the second row we could see all of the nuances of Spader's expressions. He does a lot with his face and that petulant smirk. That manner of spitting out his arrogance and contempt that does not suffer fools (the human race) lightly. Mamet spares us Spader's signature seductive, self confident, sexism and misogyny. Unlike Alan Shore his Jack does not make a pass at Susan who resembles a younger Vanessa Williams.

There is also the reality check that Spader at a thicker middle age is not the cute seducer of his 1989 "Sex, Lies and Videotape." Here we encountered a more menopausal incarnation. We are asked to feel that Jack respects Susan's ability and talent. He admires her mind over the body. But Jack is not beyond putting her in the sequined dress and humiliating her for the benefit of the jury.

For Susan, as the plot devolves, that is just another act of racism, sexism and exploitation of a black woman by a white man. She may be right as that issue explodes the firm. But in the point of view of Henry, as a member of the firm, it is not out of line for Jack to ask Susan to take one for the team.

Henry the pragmatist and up from poverty black attorney does not buy into Susan's privileged, Ivy League, sense of politically correct entitlement. It seems he has seen through her from the beginning, opposed her being hired, and refers to her as Jack's "science project."

Susan emerges as the heart and soul of Mamet's play. It is really about her and not the poor fool, rich, white, alleged rapist. In Mamet's treatment of race, at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the focus is on the collective unconscious, shame and rage, of a generation of Ivy League educated, young black professionals. Duh, how timely, when like, we have a black president, Barack Obama. Is Susan a slice of Obama which, like revenge, is best served cold?

Through a series of blunders, or are they, Susan has placed the firm in a tough spot. The ethics of law demand that every accused person is entitled to an adequate defense. Attorneys agonize about working to exonerate clients whom they know in their hearts and minds are guilty of horrendous crimes. But Susan appears willing to jeopardize her career, risk being disbarred, by using insider knowledge to undermine and sabotage the case.

Her sense of social justice and politically correct entitlement comes head on with professional ethics. Mamet seems to be indicting a generation of black professionals who may want to have it both ways. They enjoy the status and privileges of their achievement but also, when moved by conscience, like Susan, might opt to exercise that authority as leverage for payback. To get whitey. Which is how the play ends, mostly as a wash. The audience, which leaped to its feet with a standing O, is left to sort it out on the way home over bridges and through tunnels to their mostly lily white burbs.

Judging from the reviews this latest play is being regarded as minor and an interesting failure. Perhaps Mamet is slipping. Surely this drama lacked his usual vicious left hook. It was more like two rounds of rope a dope. But it left me deeply troubled, struggling with my own sense of horrendous history, racism in America, guilt and shame. In this play nobody got off least of all the audience.