Big Brother Is Watching You at the Rose Art Museum

Balance and Power: Performance and Surveillance in Video Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 09, 2006

Curated by Michael Rush Including: Andy Warhol, Vito Acconci, Bruce Naumann, Jill Magid, Tim Hyde, Sophie Calle, Jim Campbell, Peter Campus, Jordan Crandall, Harun Farocki, Subodh Gupta, Kevin Hamilton, Tiffany Holmes, Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar, Kristin Lucas, Steve Marin, Jenny Markatou, Jonas Mekas, Muntadas, Martha Rosler, Julia Scher, and Kiki Seror Organized by

As Michael Rush, the director of the Rose Art Museum and curator of "Balance and Power: Performance and Surveillance in Video Art" informs us in the twelve page, illustrated pamphlet that accompanies the exhibition, the first presentations of video art as we have come to understand the medium occurred within months of each other in 1965. "On September 29, at a party in an underground space below the Waldorf Astoria Andy Warhol showed raw footage of conversations with his collaborator Edie Sedgwick tapes using a Norelco slant-tracked video recorder. On October 4, at the Café Au Go Go,

By the end of the decade artists had broadly embraced the medium although initially it was cumbersome and expensive. Significantly one of the first applications of the medium and an impetus for its manufacture and distribution was for the purpose of security surveillance in banks. It was quickly embraced to spy on radical activities and protesters and became standard equipment for law enforcement. Rush informs us that some 500,000 high resolution cameras track the streets of

As Rush states "…It is not news that Big Brother is watching. He's been polishing his binoculars for a long time and now he's taking up residence inside our heads. While some of these trends can be catnip for anti-government isolationists, they can also be material for the tireless probings of artists whose interests in the full extent of the human condition can lead, at times, down dark paths…Much of the first decade of video art was preoccupied with critiques of television, movies and political systems."

It is interesting to view an ambitious video exhibition at the Rose which recalls the pioneering efforts of an earlier curator for that institution, Russell Connor, who staged a video survey in 1970. The Rose has long championed the medium and I recall a performance some years back when Charlotte Morman performed on cello while wearing Nam June Paik's TV Bra which one regarded at the time as an avant-garde take on the boob tube. In the late 60s in

Yes this is an important exhibition but it suffers the generic problems of video oriented multi artist projects. The installation itself, divided into tent like projections of enlarged individual works by several artists, clusters of monitors on stands and a couple of wall and table mounted monitors, is not, inherently, other than the information of each video, a particularly visual experience. The overall concept of the installation was created by Antenna Design Group from

While one engaged with a range of individual works there was less of a sense of the impact of a whole as compared to the sum of parts. There are always issues of time, engagement and creature comfort. For example, no seating was provided and some of the works take considerable time to unfold. The quality of the blown up projects was often poor particularly vintage works which now seem quite primitive. One always wonders why the work is not presented in a theatre setting as is the case, for example, in projects at the

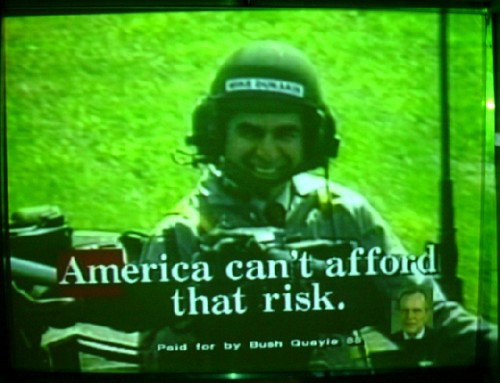

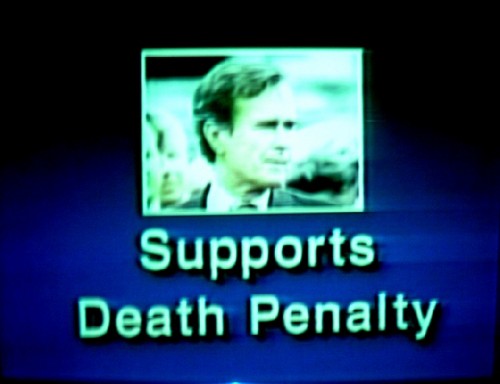

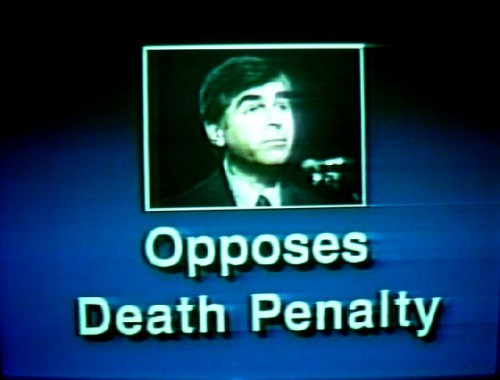

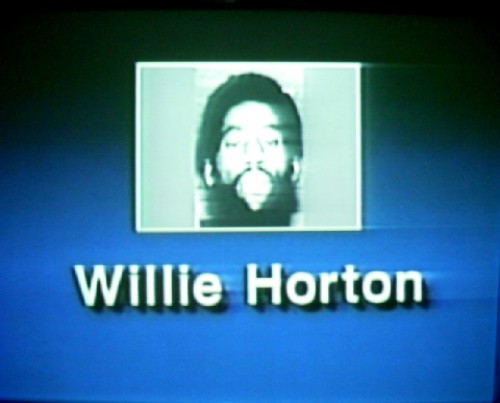

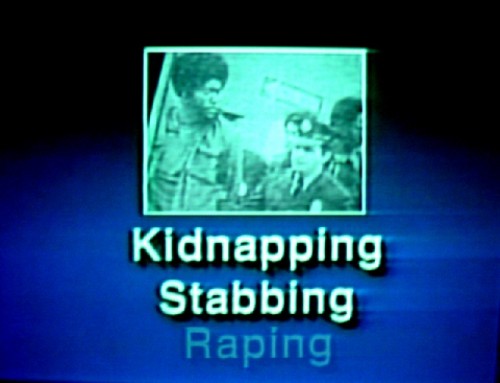

Always the primary issue for projects such as this devolves to time and patience. Just how great an effort are we willing to commit when experiencing the work? Of course that is a measure of the compelling nature of the work itself. Frankly I found "Political Advertisement V1" very absorbing and saw most of it. As is typical of Muntadas, here working with Marshall Reese, it is deadpan and informational. The piece consists of a chronological sequence of TV advertisements for Presidential campaigns. There were clips for fringe candidates such as George Wallace and Jesse Jackson. But most riveting were the dirty tricks ads against Michael Dukakis launched by George Bush the Elder. It was stunning and sad once again to view the devastating Willie Horton ads or to see unfortunate Mike looking so much like a Ninja Turtle with his head sticking out of the top of a tank. Or the smear against him for opposing the Death Penalty. All the time George was babbling about "A Thousand Points of Light." What the hell did that mean? How great it would be for PBS to pick up this project. It would be a stunning shock to mainstream

The 1963-1990 piece by Jonas Mekas "Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol in Visions of Warhol" was nothing more than a reference and time capsule. Then and now one doesn't have to really look at or pay attention to Warhol's videos, or works related to them, to understand what they are about. You don't actually have to sit through the long and soporific "Sleep" or "

There were absorbing individual works such as "Library" 2004 by Jim Campbell. It entails a wall mounted view of the grisaille steps of the New York Public Library in sharp focus and the fleeting shadow of traffic entering and leaving the building. Jill Magid's "Lobby 7" was also amusing and absorbing. She is working a small video camera under her clothes and that body image is projected on monitors being watched by shocked and aghast people passing through the area who seem oblivious to the source of the action.

With its mix of old and new work exploring an important and provocative theme this project may be considered as successful. But the usual problems of presenting multiple works and artists in a group context persist. In some aspects the superb and brilliant essay by Rush, his vision and intentions overall, may prove to be more enduring than actually viewing the exhibition. That experience was at best, mixed. Smile. You're on Candid Camera. Not.