Holiday Tour of NY Museums

From MoMA to the Met

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 10, 2016

There were sheets of rain on cold and nasty days as we made the rounds of museums during a recent week in New York.

The general game plan was to head uptown on the Madison Avenue bus around noon from our pied a terre, the National Arts Club, in Gramercy Park.

That allows for afternoons in museums. At closing time we take the Fifth Avenue bus to the TKTS booth on 47th street. From there dinner and a night of Broadway theatre.

Astrid used an umbrella but I toughed it out, a guy thing, ending up like a drowned rat soaked to the skin. It is a wonder that I didn’t come down with pneumonia.

What follows is a rundown of the museums and exhibitions we visited.

We also plan an overview of Chelsea galleries.

For your convenience the exhibitions are ordered by degree of interest and appeal.

The Picabia show at MoMA, which leads the list, is an absolute must see.

Because there is a lot of material to read I begin each listing with brief observations, more comments than reviews, followed by the museum’s press release.

Hopefully, this will be a convenient print out should you plan to be in Manhattan during the busy and festive holiday season.

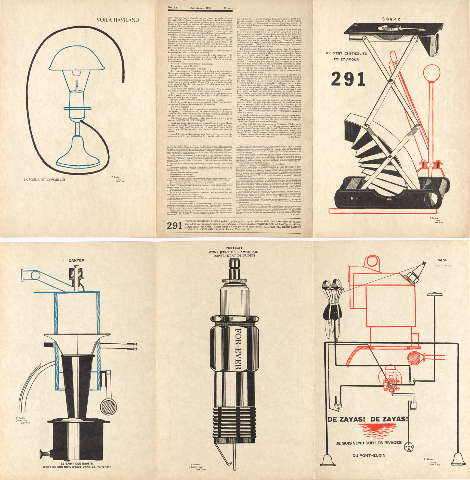

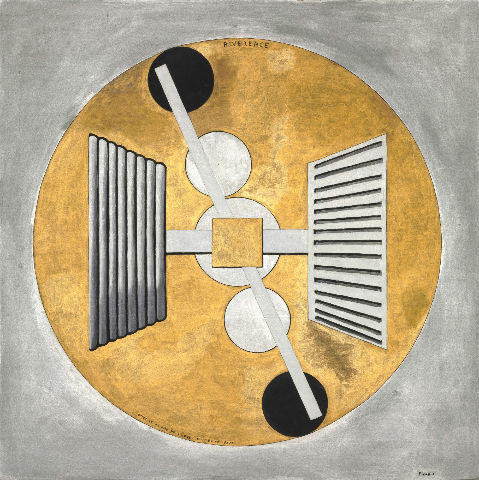

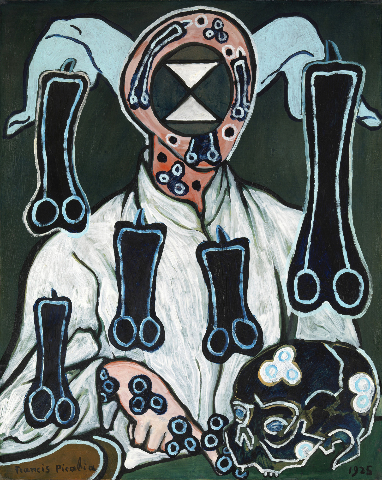

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction

Museum of Modern Art

Through March 29

Of the modernists Picabia may be the best of the artists you have never heard of.

Never a front runner he may be the most major of the minor artists.

He is much more interesting, for example, than a pretender and wannabe like the ersatz Count Balthus. He assumed to nobility by purchasing a run down chateau.

During a late phase of Picabia, advertising/ illustration like paintings, his work has an overt resemblance to the sexist surrealism of Balthus.

The plus and minus of Picabia, as this magnificent exhibition demonstrates, is that the artist never stayed put and went through many periods and phases.

Here the disparate bits and pieces of his experimemntation congeal magnificently into a singular but dauntingly complex artistic persona.

Press Release

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction is a comprehensive survey of Picabia’s audacious, irreverent, and profoundly influential work across mediums. This will be the first exhibition in the United States to chart his entire career.

Among the great modern artists of the past century, Francis Picabia (French, 1879–1953) also remains one of the most elusive. He vigorously avoided any singular style, and his work encompassed painting, poetry, publishing, performance and film. Though he is best known as one of the leaders of the Dada movement, his career ranged widely—and wildly—from Impressionism to radical abstraction, from Dadaist provocation to pseudo-classicism, and from photo-based realism to art informel. Picabia’s consistent inconsistencies, his appropriative strategies, and his stylistic eclecticism, along with his skeptical attitude, make him especially relevant for contemporary artists, and his career as a whole challenges familiar narratives of the avant-garde.

Francis Picabia features over 200 works, including some 125 paintings, key works on paper, periodicals and printed matter, illustrated letters, and one film. The exhibition aims to advance the understanding of Picabia’s relentless shape-shifting, and how his persistent questioning of the meaning and purpose of art ensured his iconoclastic legacy’s lasting influence.

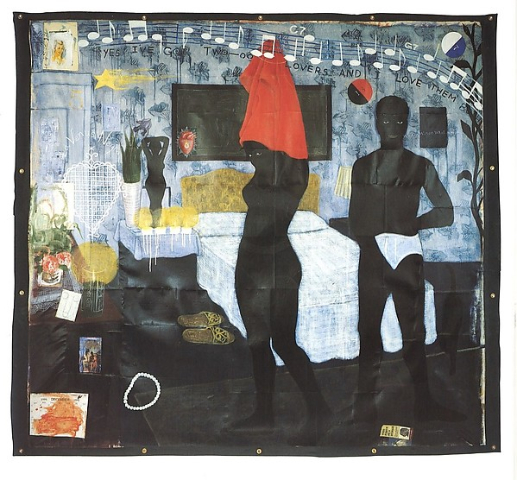

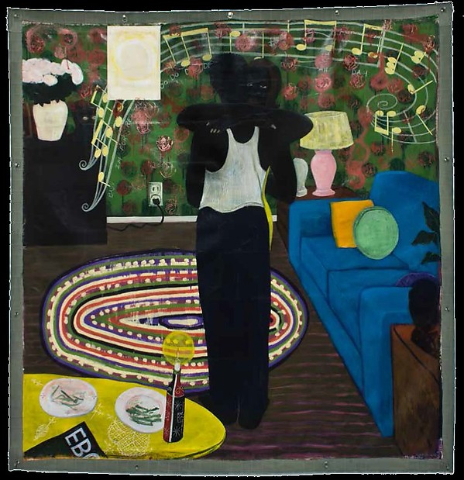

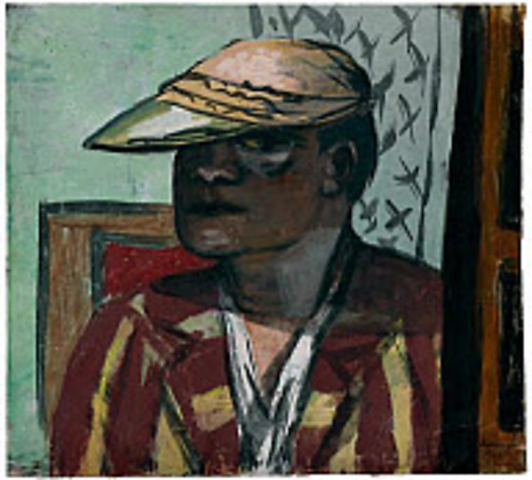

Kerry James Marshall; Mastry

Met Breuer

Through January 29

This retrospective is appearing prominently on end of the year honors lists of New York critics.

Some years ago, as an emerging artist, he did not make the cut for the Whitney Biennial. He was working in Chicago and there is always a bias for New Yorkers.

The Whitney on Madison Avenue has decamped for downtown. The Marcel Breuer designed landmark has now been leased by the nearby Metropolitan Museum to expand its modern and contemporary programming.

There is some poetic justice in seeing this magnificent retrospective sublimely installed on two floors in the building where he was formerly rejected.

Press Release

This major monographic exhibition is the largest museum retrospective to date of the work of American artist Kerry James Marshall (born 1955). Encompassing nearly 80 works—including 72 paintings—that span the artist's remarkable 35-year career, it reveals Marshall's practice to be one that synthesizes a wide range of pictorial traditions to counter stereotypical representations of black people in society and reassert the place of the black figure within the canon of Western painting.

Born before the passage of the Civil Rights Act in Birmingham, Alabama, and witness to the Watts rebellion in 1965, Marshall has long been an inspired and imaginative chronicler of the African American experience. He is known for his large-scale narrative history paintings featuring black figures—defiant assertions of blackness in a medium in which African Americans have long been invisible—and his exploration of art history covers a broad temporal swath stretching from the Renaissance to 20th-century American abstraction. Marshall critically examines and reworks the Western canon through its most archetypal forms: the historical tableau, landscape and genre painting, and portraiture. His work also touches upon vernacular forms such as the muralist tradition and the comic book in order to address and correct, in his words, the "vacuum in the image bank" and to make the invisible visible.

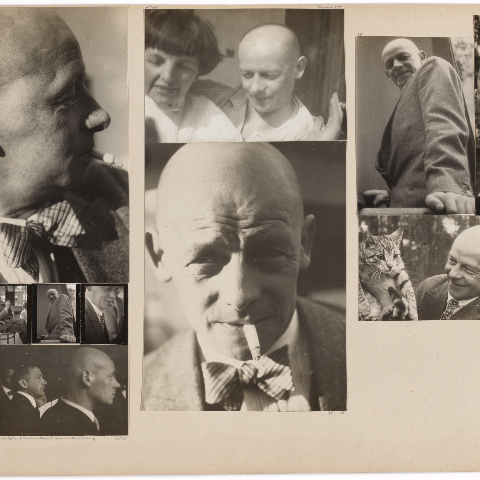

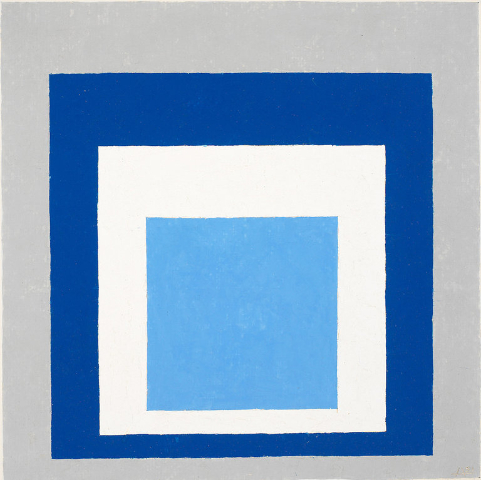

One and One is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers

Museum of Modern Art

Through April 2

Grey Steps, Grey Scales, Grey Ladders

David Zwirner Gallery

Through December 17

Reading a review of this exhibition in the Times we looked for it at MoMA.

It was not in any of the usual places for special exhibitions.

Asking a guard we were directed to the permanent collection where it is installed in a side gallery.

This proved to be a small but insightful glimpse of an unfamiliar phase of the Bauhaus period of the artist. Small format photos of fellow faculty members are arranged with an ordering sense of geometry.

There is a much larger gallery survey of studies and finished works from his signature late series the Homage to the Square. This museum quality installation is on view at the sprawling David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea. They now represent the Albers estate.

Press Release

Josef Albers (American, born Germany, 1888–1976) is a central figure in 20th-century art, both as a practitioner and as a teacher at the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Yale University. Best known for his iconic series Homages to the Square, Albers made paintings, drawings, and prints and designed furniture and typography. The least familiar aspect of his extraordinary career is his inventive engagement with photography, which was only discovered after his death. The highlight of this work is undoubtedly the photocollages featuring photographs he made at the Bauhaus between 1928 and 1932. At once expansive and restrained, this remarkable body of work anticipates concerns that Albers would pursue throughout his career: seriality, perception, and the relationship between handcraft and mechanical production.

The first serious exploration of Albers’s photographic practice occurred in a modest exhibition at MoMA in 1988, The Photographs of Josef Albers. In 2015, the Museum acquired 10 photocollages by Albers—adding to the two donated by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation almost three decades ago—making its collection the most significant anywhere outside the Foundation. This installation celebrates both this landmark acquisition and the publication of One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers, which focuses exclusively on this deeply personal and inventive aspect of Albers’s work and makes many of these photocollages available for the first time.

Agnes Martin

Guggenheim Museum

Through January 11

When visiting the Guggenheim we always take the elevator to the top and work our way down the ramp.

That means viewing the exhibition in reverse chronological order.

It proved to be a relatively smooth and swift slide.

For the most part the work of Martin, who worked slowly and meticulously, is deeply familiar.

The pace of our perusal took on cinematic overtones, evoking an animation of film noir, as each alcove or frame revealed flickering grisaille variations quivering on the retina.

Press Release

For more than forty years, Agnes Martin (1912–2004) created serene paintings composed of grids and stripes. With an attention to the subtleties of line, surface, tone, and proportion, she varied these forms to generate a body of work impressive both in its intricacy and focus. Martin’s commitment to this spare style was informed by a belief in the transformative power of art, in its ability to conjure what she termed “abstract emotions”—happiness, love, and experiences of innocence, freedom, beauty, and perfection. This retrospective, her first comprehensive survey in over two decades, presents the scope of Martin’s output, including her biomorphic abstractions of the 1950s, signature grid and stripe compositions, and final paintings. Together these works trace Martin’s practice as she developed and refined a format to express her singular vision.

Born in 1912 in western Canada, Martin spent her childhood in Vancouver and on the open plains of Saskatchewan. In 1931 she immigrated to the United States and for several years moved often as she studied and worked as teacher. It was not until the age of thirty that she decided to become an artist. Living in New Mexico, Martin began producing abstracted portraits, still lifes, and landscapes, but as her work developed, she abandoned representational content and started painting biomorphic abstractions. In 1957 she moved to New York and joined a vibrant artistic circle. Her work soon became increasingly simplified and geometric, ultimately evolving into radical, innovative, and sometimes seemingly blank paintings made of penciled grids on large square canvases.

“In 1967, as Martin’s acclaim was growing, she abruptly stopped making art and left New York. For the next year and a half, she traveled the United States and Canada before eventually settling on a remote mesa in New Mexico. It was another four years before she began working again. Unlike the first part of her career, during which she progressed through various modes of expression, Martin now focused on exploring the possibilities of her restrained style. She continued working in this manner until the final years of her life, when she reintroduced bold geometric forms into her paintings.

One of the few female artists who gained recognition in the male-dominated art world of the 1950s and ’60s, Martin is a pivotal figure between two of that era’s dominant movements: Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. Her content—an expression of essential emotions—relates her to the earlier group, the Abstract Expressionists, but her methods—repetition, geometric compositions, and basic means—were adopted by the Minimalists, who came to prominence during the ’60s. Martin’s work, however, is more than a bridge between the two. It stands apart by never losing sight of the subjective while aspiring toward perfection. “I would like [my pictures] to represent beauty, innocence and happiness,” she said. “I would like them all to represent that. Exaltation.”

—Tracey Bashkoff, Senior Curator, Collections and Exhibitions, and Tiffany Bell, Guest Curator

Valentin de Boulogne: Beyond Caravaggio

Metropolitan Museum

To January 22

As a Brandeis undergraduate I took a seminary on Caravaggio with the brilliant art historian Creighton Gilbert.

At the time I wondered why we were spending such time and attention of an artist I had never heard of. Initially, he explained how that came to be. When he was a student at the Institute of Fine Arts it seems that he participated in a Caravaggo seminar with Walter Friedlander who had singularly rediscovered the complex Baroque master.

My seminar paper was on the Candlelight Painters of Utrecht.

We came to learn that Caravaggio had been the dominant influence on Baroque painters from numerous Italians, the Carvaggistis, to Spaniards, including Velasquez, Rembrandt indirectly through his teacher Pieter Lastman, and the French master, Georges de la Tour.

The influence of Caravaggio on the French artist Valentin de Boulogne is literal, direct and somewhat enervating.

I found this sprawling survey of a relatively obscure artist tedious to wade through.

All of Caravaggio’s uniquely brilliant tricks and tropes were there from martyrs to card sharps. But if the Italian master conveyed a stunning economy in compositon de Boulogne by ‘improving” on those themes runs to distracting excess.

While Caravaggio compressed narrative with dramatic intensity this artist routinely adds more detail and superfluous figures than we need to contemplate.

Press Release

The greatest French follower of Caravaggio (1571–1610), Valentin de Boulogne (1591–1632) was also one of the outstanding artists in 17th-century Europe. In the years following Caravaggio's death, he emerged as one of the most original protagonists of the new, naturalistic painting.

This is the first monographic exhibition devoted to Valentin, who is little known because his career was short-lived—he died at age 41—and his works are so rare. Around 60 paintings by Valentin survive, and this exhibition brings together 45 of them, with works coming from Rome, Vienna, Munich, Madrid, London, and Paris. Exceptionally, the Musée du Louvre, which possesses the most important and extensive body of Valentin's works, is lending all of its paintings by the artist.

Although he is not well known to the general public, Valentin has long been admired by those with a passion for Caravaggesque painting. His work was a reference point for the great realists of the 19th century, from Courbet to Manet, and his startlingly vibrant staging of dramatic events and the deep humanity of his figures, who seem touched by a pervasive melancholy, make his work unforgettable.

Jerusalem: 1000 to 1400; Every People Under Heaven

Metropolitan Museum

To January 8

When it comes to epic overviews such as this no American museum can match the Met.

This is a stunning feast of objects from a range of people and religions. It richly coneys the complexity of a city sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims.

Press Release

Beginning around the year 1000, Jerusalem attained unprecedented significance as a location, destination, and symbol to people of diverse faiths from Iceland to India. Multiple competitive and complementary religious traditions, fueled by an almost universal preoccupation with the city, gave rise to one of the most creative periods in its history.

This landmark exhibition demonstrates the key role that the Holy City played in shaping the art of the period from 1000 to 1400. In these centuries, Jerusalem was home to more cultures, religions, and languages than ever before. Through times of peace as well as war, Jerusalem remained a constant source of inspiration that resulted in art of great beauty and fascinating complexity.

This exhibition is the first to unravel the various cultural traditions and aesthetic strands that enriched and enlivened the medieval city. It features some 200 works of art from 60 lenders worldwide. More than four dozen key loans come from Jerusalem's diverse religious communities, some of which have never before shared their treasures outside their walls.

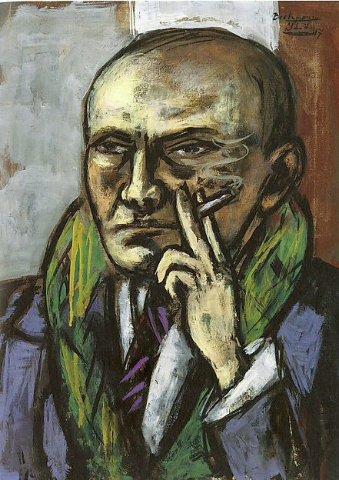

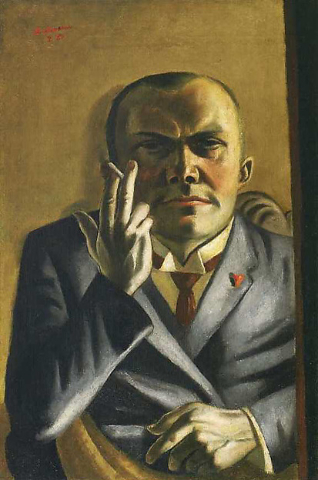

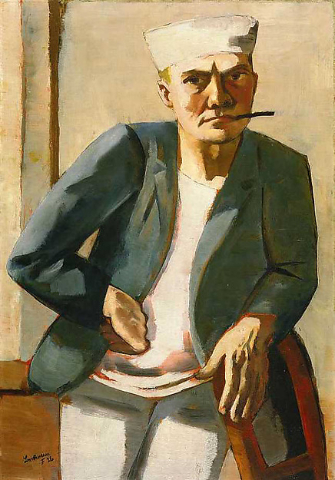

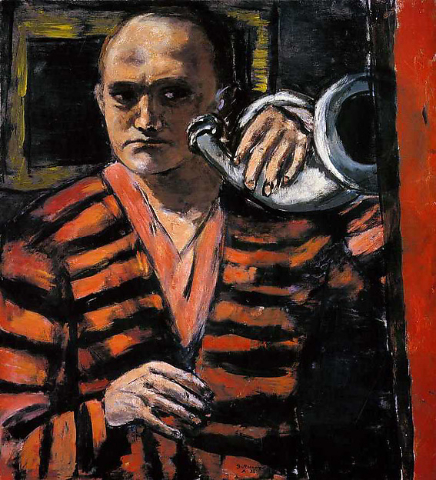

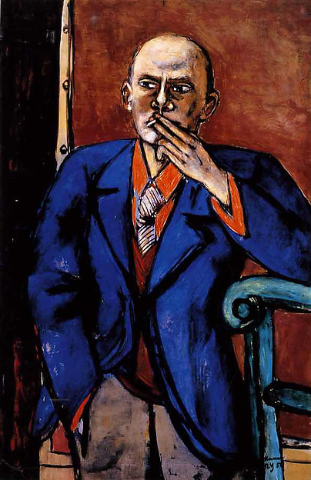

Max Beckmann in New York

Metropolitan Museum

Through February 20

The overview of Beckmann in New York combines familiar works borrowed from museums as well as a number or rarely seen paintings from private collections.

Press Release

This exhibition puts a spotlight on artist Max Beckmann's special connection with New York City, featuring 14 paintings that he created while living in New York from 1949 to 1950, as well as 25 earlier works from New York collections. The exhibition assembles several groups of iconic works, including self-portraits; mythical, expressionist interiors; robust, colorful portraits of women and performers; landscapes; and triptychs.

During the late 1920s, Max Beckmann (1884–1950) was at the pinnacle of his career in Germany; his work was presented by prestigious art dealers, he taught at the Städel Art School in Frankfurt, and he moved in a circle of influential writers, critics, publishers, and collectors. After the National Socialists labeled his works "degenerate" and confiscated them from German museums in 1937, Beckmann left the country and immigrated to Holland, where he remained for 10 years. In 1947, he accepted a temporary teaching position in St. Louis, Missouri, and in September 1949, he moved to New York City, which he described as "a prewar Berlin multiplied a hundredfold." Life in Manhattan energized him and resulted in such powerful pictures as Falling Man (1950) and The Town (City Night) (1950).

In late December 1950, Beckmann set out from his apartment on the Upper West Side of New York to see his Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket (1950), which was on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the exhibition American Painting Today. However, on the corner of 69th Street and Central Park West, the 66-year-old artist suffered a fatal heart attack and never made it to the Museum. The poignant circumstance of the artist's death served as the inspiration for this exhibition.

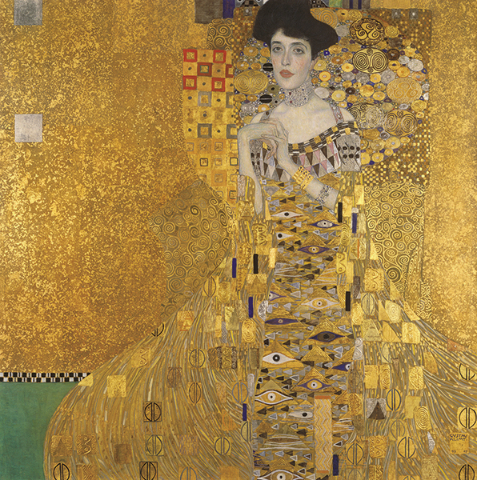

Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age: 1900-1918

Neue Galerie

Through January 16

This exhibition underscores the brilliance of culture in Vienna during the era before and after WW1. Most of the works on view will be readily familiar.

Press Release

This exhibition examines the Klimt's sensual portraits of women as the embodiment of fin-de-siècle Vienna. The show is organized by Klimt scholar Dr. Tobias G. Natter, author of numerous publications about Gustav Klimt and the art of Vienna 1900, including the indispensable catalogue raisonnée of Klimt’s paintings, published in 2012. The Neue Galerie is the sole venue for the exhibition, which will be on view through January 16, 2017.

The exhibition includes approximately 12 paintings, 40 drawings, 40 works of decorative art, and vintage photographs of Klimt, drawn from public and private collections worldwide. Central to the exhibition will be the display of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912), which are shown side-by-side for the first time since 2006. Adele Bloch-Bauer was an important Klimt patron and notably, the only subject the artist ever painted twice in full length.

Highlights of the show include some of Klimt’s most important society portraits: Portrait of Szerena Lederer (1899), which portrays the woman who built up the most important Klimt collection of her era; Portrait of Gertha Loew (1902); Portrait of Mäda Primavesi (1912); Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914-16), daughter of Szerena Lederer; and the unfinished Portrait of Ria Munk III (1917). These major works cover the gamut of Klimt’s portrait style, from his early ethereal works influenced by Symbolism and the Pre-Raphaelite movement, to his so-called "golden style," as well as his almost Fauvist depictions.

The influence of fashion design among society women in fin-de-siècle Vienna also plays a key role in the installation. Shanghai-based artist and designer Han Feng was commissioned to create three one-of-a-kind fashion ensembles inspired by prevailing styles of artistic reform dress and the designs of Emilie Flöge, an important Viennese fashion designer and Klimt’s muse. Special hats and style accessories by paper artist Brett McCormack also adorn full-scale mannequins located throughout the show.

Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) was a central figure in the cultural life of Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century, and provided a crucial link between nineteenth-century Symbolism and the beginning of Modernism. Klimt’s iconic Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), on permanent display at the Neue Galerie, is accompanied by a significant group of preparatory drawings for the painting, which he created beginning in 1903. The show includes a unique historical reproduction (1951) of the mid-sixth century mosaic of Empress Theodora from the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, which provided Klimt with an important point of inspiration for the first portrait of his patron Adele Bloch-Bauer.

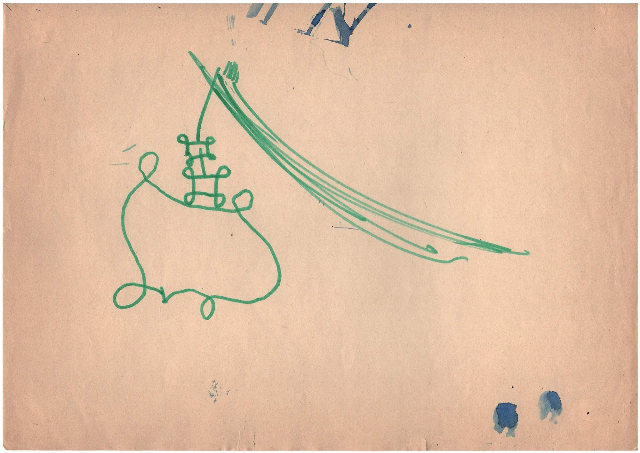

Kai Atthoff: and then leave me to the common swifts

Museum of Modern Art

Through January 22

Most visitors to this installation will find that it makes no sense. It’s experimemntal approach makes it a perfect sidebar to the Picabia show next to it. You have to stand on line to get into the gallery. Much of it has a similarity to the cluttered bedroom of a troubled and obsessive adolescent. Is this art or a bunch of stuff?

Press Release

Within an environment envisioned by the artist upon seeing the gallery allotted to him, he arranges work stemming from his early youth to the very present, in a manner of a child being handed toys, new and old: some are cherished and idolized, some are semi-precious in rank, some are abandoned and neglected in slumber of increasing hate generating towards them. Some are loved to the utmost, so much he’d want to hold onto them until the very last moment before death, and beyond.

The work being treated as such will be comprised of fragments of former larger scale environments, drawings, paintings, objects found and fabricated. In ‘and then leave me to the common swifts’, nothing is an attempt of recreating the original composition of when these works were displayed each for its first time. Instead the artist gives in to whatever his innate forces originating in his emotions command him to do upon the encounter with this work, his very own, for the most part. The result is further also constrained by time or its lack, and the pressure created by complex sociological processes, which sometimes leads the artist to surrender to a fatalism otherwise strongly fought.

Maurizio Cattelan’s America

Guggenheim Museum

Ongoing

The droll premise of this controversial work by Maurizio Cattelan is that a solid gold toilet is a metaphor for America. It’s an amusing idea but you may not give a shit.

Press Release

Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan’s bold, irreverent work skewers social complacencies and reimagines cultural icons. On the occasion of his 2011–12 retrospective at the Guggenheim, which featured virtually every work he had ever made suspended from the oculus of the rotunda, Cattelan announced his retirement from art making. Five years later, he returns from this self-imposed exile with a new, ongoing project at the museum. For “America” Cattelan replaced the toilet in this restroom with a fully functional replica cast in 18-karat gold, making available to the public an extravagant luxury product seemingly intended for the 1 percent. Its participatory nature, in which viewers are invited to make use of the fixture individually and privately, allows for an experience of unprecedented intimacy with a work of art. Cattelan’s toilet offers a wink to the excesses of the art market but also evokes the American dream of opportunity for all—its utility ultimately reminding us of the inescapable physical realities of our shared humanity.