Touring Chelsea Galleries

A Selection of Exhibitions

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 19, 2016

During a recent visit to Chelsea we made our way through parallel streets with their cluster of galleries. During the busy holiday season there is always an enticing range of major shows. We caught the last weekend of some exhibitions while several major galleries were closed for reinstallation.

We have already reported on a multiple gallery project of recent work by Ai Weiwei. Also in a museum overview we discussed the connection of a major show of Josef Albers at Zwerner Gallery concurrent with a show of his photo collages at MoMA.

What follows is a selection of exhibitions of particular interest.

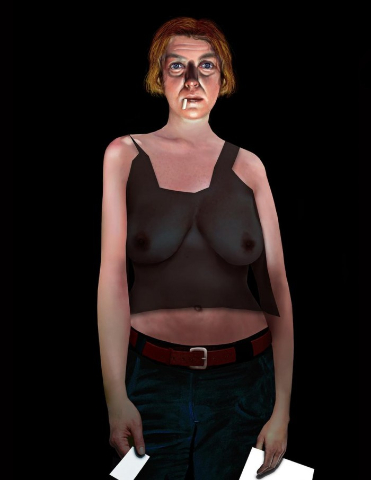

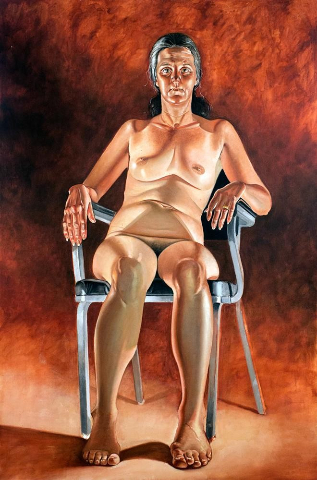

Alfred Leslie

The Toast is Burning

Bruce Silverstein Gallery

535 W 24th St New York

New York 10011

Because of strong critical response the exhibition of realist works by Alfred Leslie “The Toast Is Burning” was extended beyond the November 17 closing.

Long at the forefront of figurative realists of his generation there was something odd and unsettling about some of these works.

They are entirely computer generated but conform to the compositions and tropes that have been the norm for his works over several decades.

When he broke from abstraction as a promising artist of the so called third generation of abstract expressionists he pursued a treatment of dramatic chiaroscuro that evoked the Italian Baroque artist Caravaggio.

This was seen most explicitly in his masterpiece "The Death of Frank O’Hara" (the poet and critic who was killed when struck by a dune buggy on Fire Island) in a composition derived from Caravaggio’s “Entombment.”

The tides of critical taste and ever roiled whims of ambitious emerging curators have marginalized the realist movement.

The artist has continued to develop and evolve. Because of the demands of craft and technique it takes longer for realist painters to mature.

Now 89 the artist has taken on new technical challenges.

The digital works look like his paintings but with disarming and difficult to evaluate differences.

We asked a gallery associate for information. They are one of a kind, computer-generated, printed images. She was not able to identify the program used by the artist but it entails using a pen like device on a pad. So the artist is able to draw and see the image develop on the screen. One imagines a daunting learning curve in order to create works of such remarkable quality. Then the question arises as to why? The results are close to his paintings so in just what manner is there incentive to undertake the project?

One would assume that by using a digital format that would allow for editioning prints. Curiously the artist has opted not to do that.

The gallery press release included an excerpt from a recent interview.

"There’s a straight line from my post abstract paintings to the Pixel Scores…The Pixel Scores are not better because I do it this way—they’re just different in that it’s my way. We all work to put together the discontinuities of the things that we see all the time…I like to think of everything as automatic artifice, from images greatly disproportionate in scale to kitschy images of marshmallow clouds and whatnot, it’s all intermingled in these Pixel Scores. It’s all complete artifice, bound together—I hope—by first-class formal attributes."

The exhibition also includes superb examples of his familiar painted figurative works and drawings.

Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Project

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

100 Eleventh Ave @ 19th Street

New York, New York

Extended through January 21, 2017

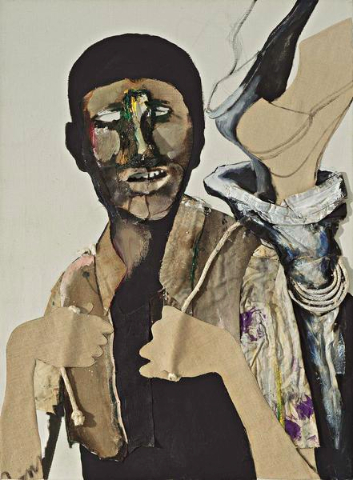

Born in Georgia the work of Benny Andrews (1930-2006) conflated earthy roots and a self imposed primitivism, with razor sharp wit and scathing agit-prop.

First impressions convey simplicity, an outsider sensibility of an autodidact, but Benny was anything but.

After a stint in the military, with funding from the GI Bill, he enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1958, he completed his BFA and moved to New York City.

His running buddies were the leading figurative expressionists. That included summer in Provincetown. It’s where I met him and was inspired to curate the exhibition Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emilio Cruz, Earle Pilgrim and Bob Thompson. The show of four African American Artists was organized for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum and traveled to the gallery of Northeastern University. I was greatly assisted in that project by Carl Hecker the director of the David Anderson Gallery. He loaned a major work by Bob Thompson from the estate of Martha Jackson.

Previously I spent a P’Town weekend with Benny as guests of Rhoda Rosmore an arts patron. While researching that show I visited with Benny in his NY studio. At the time, 1982 to 1984, he directed the Visual Arts Program, a division of the National Endowment for the Arts.

When the leading figurative expressionists Jan Muller and Bob Thompson died young a group of like-minded artists formed Rhino Horn. In addition to Andrews the group, which organized a number of exhibitions, included Jay Milder, Peter Passuntino, Nicholas Sperakis, Peter Dean, Michael Fauerbach, Bill Barrell, Leonel Gongora, and Ken Bowman.

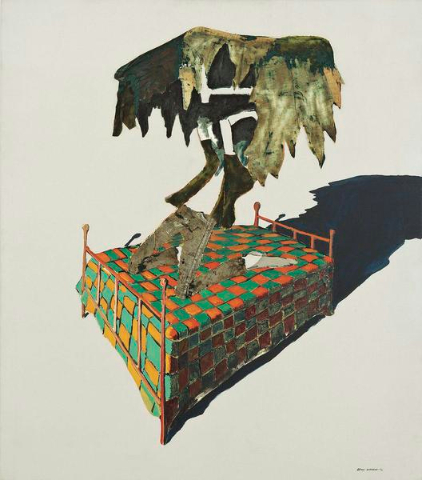

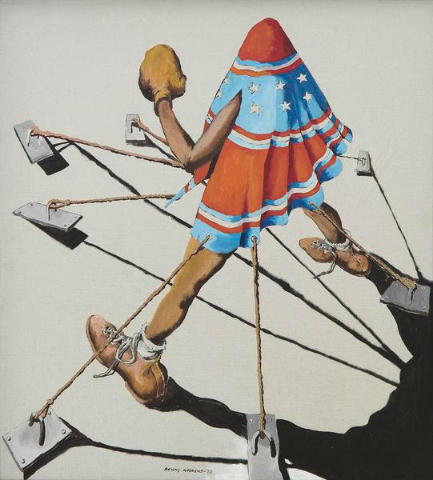

The centerpiece of the exhibition is Circle (Bicentennial Series), 1973 oil on twelve linen canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage

120 x 288."

The ingenious joining of multiple, easel-scaled paintings to form a broad panorama reminded me of the confines of his modestly scaled studio. It took considerable planning and design to create such a large work.

There is a central figure tied down to the four corners of a bed. Given the gaping, bright red, watermelon-evoking wound in his chest we assume that he is a martyr figure. Above him hovers a deus ex machina device which reminds me of Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony.”

Ropes extend from the machine in several orientations. They appear to be manipulated like marionettes by a circle of rural Southern men and women. They circle as observers and seemingly participants in this ritual of sacrifice. Their body language and expressions range from agitated to apathetic.

The intentionality of the work is not didactic. It is a norm for Andrews to create aesthetic conundrums.

The elements of his work entail diverse traditions and sources. There is an evocation of the narrative traditions of the Marxist social realists of the 1930s. In particular there are graphic references to Robert Gwathmey, Philip Evergood and Ben Shahn. Andrews was also interested in aspects of modernism particularly surrealism and collage derived from cubism. Forms lift off the picture plane. A nose, for example, is sculpted with a element of projecting cloth.

There are those ropes which play a prominent role in Circle (Bicentennial Series). One may consider their use in a straight line from Picasso’s early collage Still Life with Chair Caning.

The exhibition includes drawings that are studies for the painting. There are line drawings that depict vignettes of Georgia’s sharecroppers and blues musicians.

They underscore that while Andrews had a brilliant career as a teacher and activist in New York he never lost touch with his roots and heritage growing up in rural Georgia.

Mark di Suvero

Paula Cooper Gallery

534 West 21st St.

November 3 to December 10

In her recently published book "Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Art" the author, art historian Judith E. Stein, discussed the unique relationship between the eccentric dealer and Mark di Suvero who creates monumental metal sculptures. (Link to interview with Stein on Bellamy.)

The artist was born in 1933 in Shanghai. It is unclear that it was a factor in the relationship with Bellamy (1927 to 1998) whose mother was a doctor from China.

For a variety of reasons, including self abuse and a refusal to go along with commercial trends in the art market, Bellamy quit minding the store and set up quasi galleries (Oil and Steel) with odd hours on warehouse properties where di Suvero maintained studios. In those last years of exclusively representing the sculptor Bellamy functioned like a curator organizing exhibitions, like one at Storm King in upstate New York, and overseeing publications.

Bellamy took up photography with the primary objective of documenting di Suvero’s work. Having it done professionally proved to be too costly. Later Bellamy handed over the archive to settle a debt.

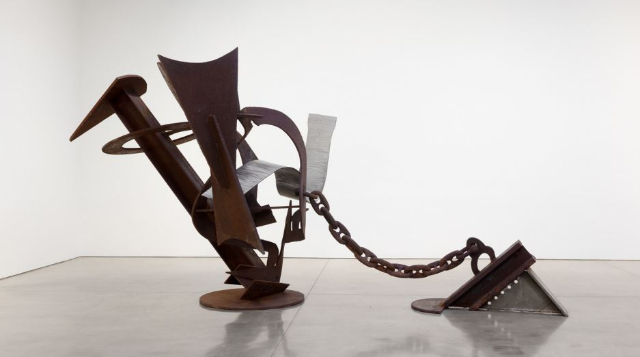

The vaulted space of Paula Cooper’s gallery was adequate to show several major works as well as drawing in the smaller front gallery.

There was a hammer hanging next to one piece. It was an invitation to bang on the can. A professor conducting a gallery tour class rather tentatively did so. The interaction amused me.

The work does not conform to any easy formula for critical dialogue. There is often the agenda of scale. By definition these are imposing and impressive works.

Encountering them casually on a tour of galleries underplays their position in the art of his generation. In a gallery run of many exhibitions and absorbing a plethora of visual information it is often difficult fully to appreciate the singularity of individual experiences.

Viewing works by di Suvero over decades in a range of settings has always been evocative and even daunting. It is always flabbergasting to consider the alacrity with which he assembles and manipulates massive, weighty elements with seeming impunity.

From Stein’s bio we learn that representing the sculptor was a hard sell. The works demand adequate space. In museums and for major collections that status and accommodation is accorded to a short list of renowned artists. Not surprisingly most often the large works are viewed in natural settings.

That was the case for Storm King. In 2013 the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art curated eight monumental sculptures for a year-long exhibition in Crissy Field. There have been similar projects for other settings.

For this exhibition you have to walk around the epic pieces and view them from multiple vantage points. There is an element of whimsy.

Anchored to a circular base we see a cluster of welded elements conjuring a floral arrangement. It is tethered to a smaller cluster several feet away. An enormous chain connects them like a surreal piece of gigantic jewelry.

Carrie Mae Weems

Scenes and Take

Jack Shainman Gallery

October 28 to December 10

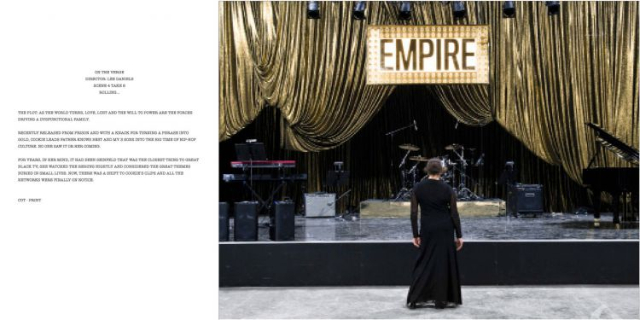

Now 63 Carrie Mae Weems in among the most celebrated narrative photographers of her generation.

There was a 2014 retrospective of her work at the Guggenheim Museum. This was her first body of new images since that museum exhibition.

For artists following retrospectives there is the frequent phenomenon of post-project blues. Having accomplished such a landmark there is soul searching to find new directions to explore.

In that sense the Shainman exhibition is a departure and rupture as well as deeper exploration of issues and concerns.

The earlier, now iconic images such as “Kitchen Table Series,” were often galvanic for their simplicity. In that aspect the new pieces are technically more complex but also more remote and oblique.

She has created a persona, herself in disguise, who is a single figure on the set of television shows like “Empire,” “How to Get Away with Murder” and “Scandal,” all of which feature black characters. The pieces are large, and horizontal. In a white space on the left is a passage of text that explores the image.

Other than her haunting persona there is no action. We contemplate why the celebrated actors of these popular and critically acclaimed shows are absent.

In an interview with the Times she discussed aspects of race in film and television. From her perspective these popular programs are both significant as well as disappointing. The social and political ideas expressed with a journalist are not so readily accessible in the work itself. Here the connection to the viewer is more oblique than it was in the past. There is an appeal of accessible subject matter but we don’t quite get her point.

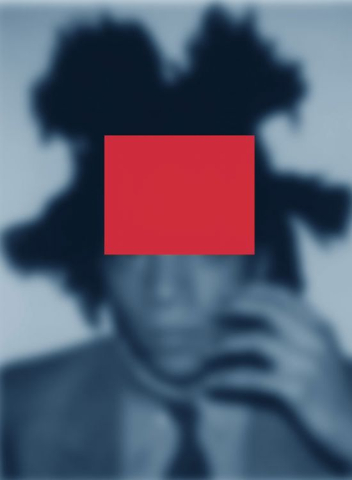

Other rooms of the gallery explore “Blue Notes” (2014) and other themes. These are “portraits” of single black figures some of whom are readily identified celebrities despite the fact that the images are deliberately blurred.

We quickly recognize the signature dreads of the deceased artist Jean Michel Basquiat. Partly obstructing his face is a block of bright primary color. Exploring the images we try to identify her subjects which are familiar and not.

“All the Boys” (2016) responds to recent police killings of African-Americans, with portraits of black men in hooded sweatshirts.

The Shainman show also includes “Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me,” a 2012 video installation that uses a hologramlike effect to create transparent ghostly illusions.