Terry Teachout’s Definitive Book on Duke Ellington

We Loved Him Madly

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 21, 2013

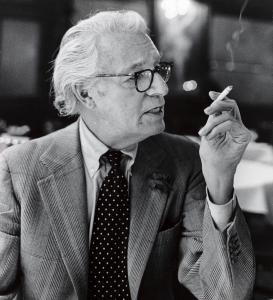

Wall Street Journal theatre critic, Terry Teachout, is on the short list of most respected in the field. He came to writing criticism from an earlier career as a jazz bass player. The confluence of that considerable range of interests resulted in the superb biography Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong.

The book was then transformed into his first play Satchmo at the Waldorf which was co-produced by Shakespeare & Company and Long Wharf Theatre. It is a one man play starring the renowned classical actor John Douglas Thompson. The play opens off Broadway with rehearsals starting in January.

Now Teachout has published an even better jazz biography Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. While Armstrong was the singular soloist of early New Orleans jazz for Ellington (Edward Kennedy Ellington April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) the orchestra was his instrument. By definition it is a far more complex and fascinating narrative. Add to that Duke’s byzantine opacity and sharp demarcation between the suave, sophisticated, charming, elegant public persona and a guarded, secretive, private life juggling a menagerie of women from groupies to mother, sister and ersatz wives. He had a single child, Mercer, who was Julliard trained. He eventually joined the brass section of the orchestra and led it after his father's death.

It was an Ellington mantra to intone to audiences “We love you madly.” Off stage he could be a cruel and heartless lover not only to the countless women in his life but also to the brilliant, unique and eccentric musicians and associates who were essential to his creativity.

This is not a flattering portrait. While all acknowledge that Ellington was the greatest composer of his generation in the canon of jazz he was flawed, tormented, superstitious and conflicted both in his music and private life. Teachout is measured in providing insightful praise for his greatest accomplishments and triumphs but unsparing in exposing limitations and grievous errors of judgment.

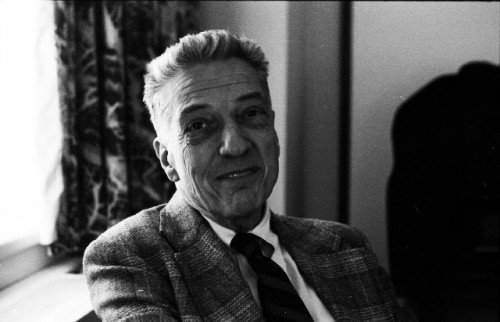

Jazz promoter and recording producer, Norman Granz, whom Duke used and abused as manager and errand boy, has the last word in this stunning page turner of a book.

Teachout writes “Everyone knows him- yet no one knows him. That was the way he wanted it. ‘To the very end, he made sure he left nothing behind that would let people know the true Duke Ellington,’ Norman Granz said. But he had: He left behind his music, the only mistress to whom he told everything and was always true.”

Having thoroughly researched and published this remarkably detailed biography reportedly Teachout is working on transforming it into a play about Ellington. The title of Duke’s autobiography, written with an exasperated Stanley Dance, is Music is My Mistress and she plays second fiddle to no one. Teachout repeatedly refers to it in a demeaning manner. It is a cautiously vetted and sanitized reflection of the well crafted suave mask of his public persona.

If Duke was faithful only to his music then what does that say of the coterie of women in his life who ranged from one nighters on the road to women who doted on and cared for him in the shadows for decades.

As Teachout demonstrates Ellington had a voracious appetite for life including gluttenous consumption of food and booze and womanizing on a level that competes with Wilt Chamberlain. At midcareer he wore a girdle to pull in the gut on stage. Eventually he quit drinking but consumed coke with three teaspoons of sugar on stage. His diet was reduced to a daily steak and grapefruit usually consumed through room service. Often he had a steak sandwich tucked in his pocket.

Keeping Duke on the road, active and creative enatiled an enormous support group of retainers. For many years his manager Irving Mills, cutting himself a fifty percent slice of royalties, covered the details of bookings, arranging transportation, dressing the band with suitable elegance, and sending regular checks to the many who depended on his generous support. Eventually, Mills acquired other clients including Cab Calloway and got very rich. Mills was but one of many including road managers who skimmed. But when he and Mills parted ways there was nobody to see to the endless details. The band got sloppy particularly in the steep decline of the final years.

These are complex and fascinating ingredients for what has the potential to be a compelling play. Success and backing for that project will largely depend upon how Satchmo at the Waldorf is received during its upcoming New York run.

The music of Duke Ellington has been a lifelong passion for me.

As a teenager two uncles got me on the right track.

My uncle James Nugent Flynn was an Ellington fanatic. He took me to see the Duke at George Wein’s Copley Square nightclub Storyville. It was the first time I had heard live jazz and the experience is etched in my memory.

It was 1954 and I was 14. What most impressed me was the color scheme of the club with walls painted Black, Brown and Beige emulating Ellington’s most famous and debated extended composition. It was also my first exposure to an integrated audience and wait staff. In later years jazz audiences were more white than black which dismayed many of the musicians.

We sat close nursing our Shirley Temples. That sax section blew me away. It was love at first sight hearing Harry Carney’s deep, guttural baritone sax. Then Johnny Hodges, who looked bored to the point of sangfroid apathy, rose to perform soft as silk alto sax solos. There was Russell Procope on tenor and Jimmy Hamilton on clarinet. I was just floored when they played “Mood Indigo.” Until that moment it was the most beautiful music I ever heard. Then Cat Anderson blew the roof off with his screeching trumpet.

During intermission my uncle who had the Irish gift of gab introduced my sister and me to the Duke. He insisted that I bring along an album to have signed. I was embarrassed that the only one I then owned was a cheap ten inch knock off that I bought in a drug store. Not skipping a beat Duke signed it. Years later, as a critic for the Boston Herald Traveler, I got to interview Ellington.

In the club that night were stacks of leftover illustrated programs from the Newport Jazz Festival then in its infancy. It was a treasure but it would be years before I got to cover Newport including the 1971 riot that for a time ended it. My story of the riot made the front page while the Globe ran the "review" of my colleague Ernie Santosuosso (filed early to meet a deadline) of the concert that never happened.

On the occasional Saturday I helped my Sicilian uncle, a hipster who had worked in WPA theatre, at his store in Newton Corner Freddy’s Music Unlimited. He was a Marxist who read Dostoyevsky and the Christian Science Monitor.

That Christmas he gave me two albums. Both LPs on Columbia Records from producer George Avakian. One was a compilation of Ellington classics and the other Louis Armstrong Sings the Music of W.C. Handy. I wore the grooves out of those platters. In those days there were listening booths in the record stores. I spent Saturday afternoons listing to Jazz at the Philharmonic, Bird with Strings and other bop classics. You had to buy at least one LP not to get the boot the next week. It's how I got a jazz education early on.

Years later I returned the favor and took my uncle Jim to hear Buddy Rich at Lennie’s on the Turnpike. After the gig we visited Buddy in his dressing room. He was sitting there in skivvies talking about appearences on Johnny Carson and gigs in Vegas. In the room was the very smashed and elegantly dressed, legendary journalist George Frazier then a columnist with the Boston Globe. His favorite theme at the time was defining who did or did not have duende. Buddy had duende. To the Max. Now and then Frazier would slur something but mostly it was me one on one with Buddy who was always good for an interview. After that night Fraizer went on a bender holed up in a motel on Morrissey Boulevard. He was off the grid for a couple of weeks. Nobody at Locke Ober's saw him for his usual lunch of Finnan Haddie.

In the early 1970s, when Ellington was booked for a week at Boston’s Paul’s Mall on Boylston Street, the club owner Freddy Taylor set me up for an interview.

It was across the street at the Hotel Eliot. Approaching the suite there was a loud commotion. Suitcases were being tossed into the hall and I heard, but never saw, an angry woman yelling “Ok for you Duke.”

The door open I entered cautiously to find an empty living room. Softly I called out “Duke, Duke.”

He entered imperiously from the bedroom as I introduced myself.

It was mid afternoon but he was wearing a long, elegant dressing gown. Keeping his conk in place, by then decidedly unfashionable in the era of the Afro, was a due-rag. It's a scull cap fashioned from the tied up end of a nylon stocking.

We settled on the couch for an audience with jazz royalty. In an oblique reference to the incident I had walked in on he said archly "Some people can be so rude." Asking questions I hastily took notes. He looked closely at what I was writing. I had learned to focus interviews on what was of interest to the musicians and their upcoming projects.

“I’m working on my favorite subject” he said with a dramatic pause. “Me.” He described what would become Music is my mistress, and she plays second fiddle to no one (Da Capo Press, 1976).

Looking at my notes he said “I think you have enough and now I have to lay my head on some feathers.”

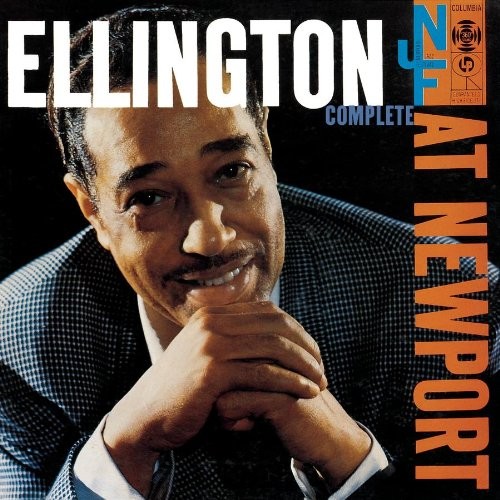

Ellington was all but washed up when Wein reluctantly booked him for the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. The big band era had passed and Duke was struggling to make an expensive payroll. The band lacked discipline and several members “The Airforce” including tenor sax player Paul Gonzalves, were hooked on smack. They were often tardy for rehearsals and performances.

For Newport Wein insisted on something new. As was his long habit Duke slapped something together which was performed without rehearsal by musicians not noted for an ability to sight read the charts.

LP albums allowing for extended compositions, and not just three minute songs, were then in their infancy. Initially, they were used to record classical music and original cast musicals like South Pacific. Columbia producer George Avakian convinced executives to allow him to make live recordings at Newport. For this he paid Wein a flat fee which underwrote the cost paying musicians. Part of the deal was hiring Ellington who was under contract to Columbia. There was also an open mike for Voice of America going out live.

Wein had Duke play a teaser set early in the program with a plan to bring him back as the closer. It infuriated Ellington particularly as he had to vamp as key players failed to make it on stage for the first, short set. It was an embarrassment. The new suite didn’t fare much better and the “live” performance was spliced with a studio take that week in New York. Avakian had booked time at Duke’s insistence.

Ellington premiered an extended three part work "The Newport Jazz Festival Suite." For years he had struggled with “Diminuendo in Blue” and “Crescendo in Blue” which followed. Finding it difficult to splice them together, a perennial issue with his extended compositions, he crafted tenor bopper Gonzalves into the middle. He hit a groove that night for some 27 electrifying choruses. The crowd went wild and fearing a riot Wein considered shutting down. Wisely, Duke continued to play past curfew and sent everyone home happy.

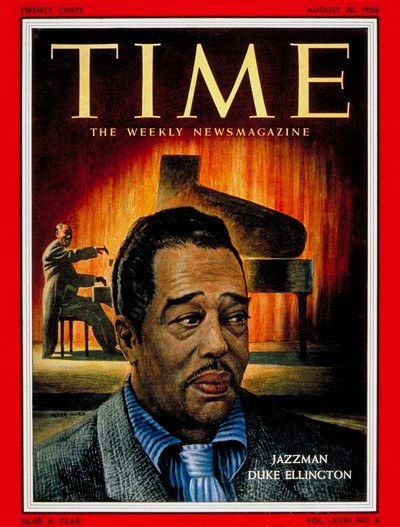

The critical coverage and word of mouth among fans had Ellington back on top. He made the cover of Time Magazine soon after and the “live” album (as much a creation of Avakian as Ellington) was and continues to be Ellington’s best seller. It has been remastered as a double CD.

Almost two decades later during that gig at Paul’s Mall Gonzalves was falling off the stand. Duke had a notorious tolerance for his miscreant musicians. As Teachout chronicles periodic attempts to impose disciple were utter failures. But Duke, who kept his distance after gigs, had a way of poking them in public.

With that grand style that was his signature he called on Gonzales to replicate his Newport triumph. He staggered to his feet and muddled through a few choruses before flopping off the bandstand.

“He has such a great sense of humor” Duke intoned gesturing to the snoring and passed out Gonzales.

The twin towers of the Big Band era were Duke and Count Basie. Ironically, they were eclipsed by the King of Swing, Benny Goodman, who fronted a great integrated band with the black musicians Teddy Wilson, piano, Lionel Hampton, vibes, and Charlie Christian, electric guitar, briefly Billie Holiday. In 1938 Goodman was the first jazz artist to perform at Carnegie Hall. For that great occasion he augmented the band by inviting musicians from the Ellington and Basie bands. Ellington, feeling snubbed and passed over, was invited but declined to attend. He was later nominated for a Pulitzer Prize which was overruled by the executive committee. A Pulitzer was awarded for lifetime achievement posthumously. He was also feted at the White House by Richard Nixon who played Happy Birthday for the Duke on piano.

When the Big Band era lapsed only Duke, Basie, Woody Herman, Buddy Rich and Stan Kenton remained but struggled. Goodman and Tommy Dorsey were long gone.

In exploring the long form of compositions Ellington aspired to advance jazz beyond dance music. When he first appeared at Carnegie Hall he performed the extended suite “Black Brown and Beige.” It garnered mixed reviews and was performed and recorded only as excerpts after that.

As Teachout explains Ellington lacked a musical education. Mostly he hired musicians because he liked their unique sounds. Then he collaborated with them to create vehicles for their assets. But routinely deprived them of publishing credit. They were generally paid a flat fee of $25. Royalties supported the great expense of sustaining the band on the road. It was his instrument and Ellington would not have it any other way.

Ellington had no interest in classical music or studying techniques for composing symphonies. Accordingly, his suites were a mélange of disconnected elements. Teachout is generally tough on these works dismissing one of my enduring favorites "The Liberian Suite” in a couple of sentences lumped together with other works.

Teachout lays out Ellington's complex relationship with critics most of whom, early on, had little or no knowledge or taste for jazz. Most were moonlighting classical critics who were less than kind to his extended compositions. Whitney Lyon Balliett (17 April 1926 – 1 February 2007) joined the New Yorker as its first full time jazz critic in 1954.

During a hilarious dinner with the blind Roland Rahsaan Kirk and his band he ranted about "The muthafuckin white so called jazz critics." He was mostly right. But I don't subscribe to how in the Ken Burns PBS Jazz series talking heads like musician, Wynton Marsalis, and critic, Stanley Crouch, managed to all but eliminate the contributions of white musicians to the history of jazz.

One of the harshest of Ellington's critics was the wealthy (Vanderbilt) dilletante, talent scout, and producer John Hammond the brother-in-law of Benny Goodman. He was a staunch backer of Basie insisting that Duke didn't swing and was too pretentious. Briefly and unfortunately Hammond was Ellington's producer during his first stint with Columbia Records. I interviewed Hammond when he published "John Hammond on Record" in 1977. We discussed Basie but not Ellington. Teachout evens the score with Hammond with choice words and brutal enecdotes.

Along the way Ellington had the uncanny luck of finding a musical genius and alter ego Bill Strayhorn (November 29, 1915 – May 31, 1967). The shy, gay Strays was everything that Duke was not. While Ellington supported him in style he consistently was kept in the background. I remember seeing him at gigs and he took the occasional turn at the piano. He wrote the band’s theme song “Take the A Train” and many of the band’s standards and suites.

While their styles of composing merged to be similar Strayhorn was diverse and well read. When Duke was commissioned to compose Such Sweet Thunder for the Stratford Ontario Shakespeare Festival most of it was the work of Strayhorn. He met with scholars and more than held his own selecting suitable characters and scenes from the plays. Ellington mostly took riffs from his musicians and expanded them into pieces. He employed copyists to write out the parts and Strays to clean them up.

Teachout is at his best unraveling the close and complex, love/ hate relationship between them. Consistently, he was denied credit for publishing and recordings. But after Ellington he was the essential heart and soul of the band. Strayhorn was tasked with projects that Duke had little time or energy to focus on from suites to several failed Broadway musicals, the film score for Anatomy of a Murder, and a TV fiasco “A Drum is a Woman.” When Strays died of lung cancer (as did Ellington) the Duke never recovered. There was a penetrating HBO documentary on Strayhorn who was every bit as much a genius as Ellington.

Ellington had an amazingly long and productive career writing and recording constantly from the early years in Washington, D.C. up to his last moments. In the hospital he had an electric piano next to the bed and was working on several projects. Shortly before he died Ellington presented his Third Sacred Music performance in London. Even though terminally ill Ellington continued to tour because he was broke. He died intestate and his publishing was sold to pay the IRS.

Having listened to Ellington for all of my adult life I thought I knew the man and his music. Now, having Teachout as a guide, I will jump back in following up on his many insights. Returning anew to the Jungle Band period of the Cotton Club in Harlem (for whites only) which brought him national fame through live broadcasts. It was a PR term which he hated. But a way of describing the signature growling plunger mutes of the brass and block chords of the reeds.

Critics affirm that the greatest period was 1940-1942 when the bookmarks of the band were the first great double bass, big band player, Jimmy Blanton (October 5, 1918 – July 30, 1942) and tenor sax player Ben Webster (March 27, 1909 – September 20, 1973).

As a bass player himself Teachout is particularly brilliant when discussing what Blanton brought to the instrument. Early on bass players were former tuba players. The inital approach was the percussive slap style of Slam Stewart (September 21, 1914 – December 10, 1987). Blanton developed the pizzicato technique which has prevailed ever since. He was also adept with the bow providing lush accompaniment to ballads.

Like the Blanton/ Webster era the band took off in new directions when it retired lesser players and hired better ones. Like original member, drummer, Sonny Greer (an alcoholic with diminished skills) replaced by the white musician Louis Bellson ("Skin Deep") then Sam Woodyard. These “infusions” included the Puerto Rican valve trombone player Juan Tizol (“Caravan”) the Cape Verdian Gonzalvez, trumpet player, Ray Nance, who also played violin, sax player, Russell Procope, trumpet player Cootie Williams and the various trombone players who covered for plunger mute trombone player Tricky Sam Nanton (February 1, 1904 – July 20, 1946).

It is interesting that Ellington had no gift for lyrics. Often they were added later to instrumentals. There was the great singer Ivie Anderson (July 10, 1905 – December 28, 1949) and I always loved Al Hibbler (August 16, 1915 – April 24, 2001). There were botched sessions with Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra. When he was unprepared for Mahalia Jackson during a studio session he just told her to sing her favorite passage from the Bible. That resulted in the stunning “Come Sunday.”

While Ellington's track record with vocalists is mixed they thrived with Basie from Jimmy Rushing to Joe Williams, Lambert Hendricks & Ross, Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Sammy Davis Jr.

In researching this book Teachout modestly states that he stood on the shoulders of others. There is a considerably body of research on Ellington who is ensconced in the canon of American music. Teachout is most generous in giving credit where it is due.

Arguably, no book on Ellington will ever surpass Teachout's mastery of weaving the elements together. Inevitably, through Duke’s unique paranoia, hypochondria, isolation, religious faith, unsatiated obsessive womanizing, personal selfishness, cruelty to colleagues and loved ones (including Mercer) we will never really know the full Duke Ellington. But Teachout gets us as close as we can ever hope for. It was with consummate sadness that I read the last words of his truly magnificent book.

For all else we have Ellington's music.

Link to website connecting to extensive on line coverage of Ellington.

Boston Globe review.

Washington Post review.

New York Times review.

Chicago Tribune review.

Terry Teachout lecture on Ellington begins after 9 minute introduction.