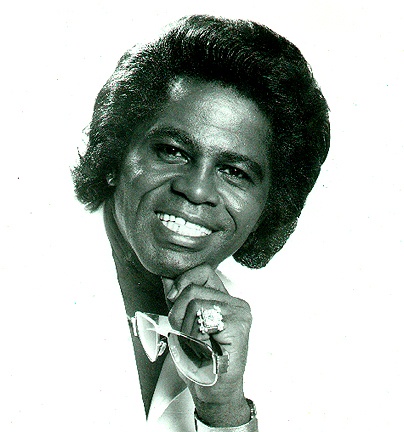

James Brown: Said It Loud, Black and Proud

Remembering the Godfather of Soul

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 26, 2006

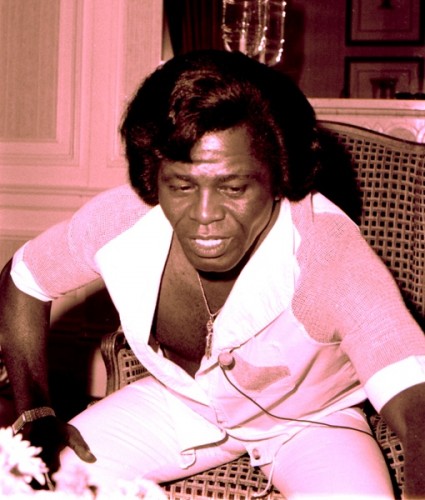

It was the small, crowded dressing room of the Sugar Shack next to the Colonial Theatre facing Boston Common. The spacious club featured soul music and catered to pimps, hookers and pushers. Late at night there was always a parade as the hos wandered in from working the zone with their pimps in outrageous outfits, fur coats with matching broad brimmed hats, alligator shoes and dripping with bling bling. James Brown was holding forth surrounded by an entourage of body guards and hangers on. He was sweating having performed a set and waiting for another.

"I used to shine shoes in front of the biggest building in downtown

Later, I interviewed him again in

In a lot of ways Brown was rougher, more remote and complex than the jazz greats I got to know and hang with. Jazz artists could be cerebral and conceptual where Brown was as earthy as the

In later years it was tough to see him perform when thicker in the middle and slower in step. But in his prime he was galvanic to the point of frightening, perhaps, the devil himself. Church going black people often referred to the Blues as Devil Music and nobody incarnated the evil force more that Brown. He didn't perform so much as cast a spell on audience which exploded when he went through the routine of multiple capes, fall to his knees, limp off stage, only to return for a comeback in "Please, Please, Please." The only way to see Brown was before a black audience. Like the Sugar Shack or earlier in the 60s when I talked my mates, Phil Bleeth and Hoey, into taking the rattler uptown to Harlem to see Brown at the Apollo Theatre. They later joined me to see Brown at

A couple of years later Arden and I visited Phil Bleeth in Clearwater, Florida where he was living with his pregnant wife, Corinne, a former model. Corinne was not glad to see any of Pheeele's derelict friends and bad influences. She was French. Need I say more. But Phil wanted to check out James Brown who was performing in nearby

James Brown meant a lot to me on many levels. Mostly I grew up as a jazz fan starting with Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Mezz Mezzrow, Duke Ellington, later Bird 'n' Diz, Mingus and Miles. I didn't know much about soul. In the early 60s I walked into Skippy White's on Lower Washington Street and asked Big John what he would recommend for a jazz fan looking to get into soul? He handed over "James Brown Live at the Apollo" on King Records. I wore out the grooves and later a friend turned me on to Smoky Robinson and the Miracles.

It was with that friend, Blind Jim, and Arden, in 1968, that we watched a WGBH special during the weekend when Martin Luther King was assassinated. Brown's concert at

But it could go the other way as well. Like a Newport Jazz Festival appearance in the late 60s. It was an afternoon performance and I was in the press area the first two rows in front of the stage. There was a fence behind us and defiant black teens were pressed up against it as Brown sang "It's a Man's World" and then "Say It Loud I'm Black and I'm Proud." It was a tense time in America and blacks were moving away from the non violence of Martin Luther King to the message of "By any means necessary" of Malcolm X. As an entertainer and role model Brown was a man in the middle staying on top of the dominant political mood of his audience. As well as facing his own demons. Perhaps he never escaped them. Even at the peak of fame and fortune in his heart of hearts he was still shining shoes in front of that tall office building. He later bought it then the man took it away.