Gerard Malanga Interview Part Two

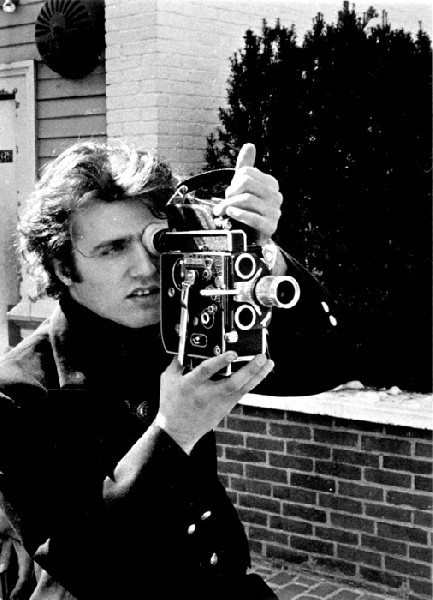

Still Shooting Black and White Film

By: Gerard Malanga and Charles Giuliano - Mar 30, 2010

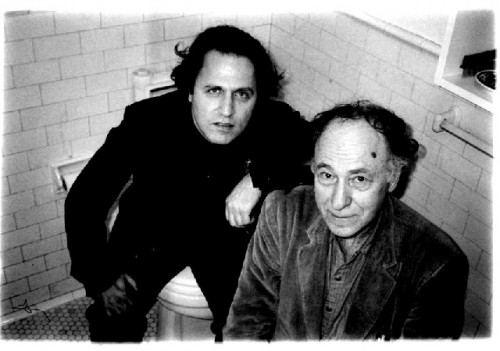

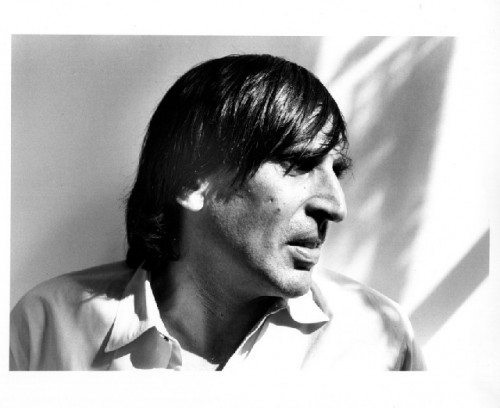

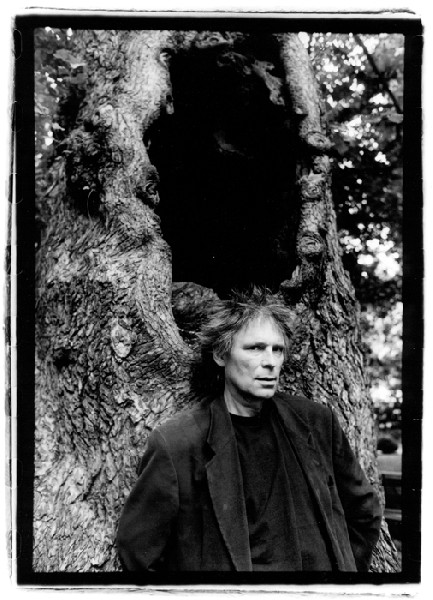

Gerard Malanga

Souls

Pierre Menard Gallery

10 Arrow Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

March 12 to April 12, 2010

Archives Malanga

CHARLES GIULIANO Most of the images that you print, publish and exhibit are vintage, black and white. Fewer and fewer photographers still shoot with film. Have you made the transition to digital cameras? If not why not? An artist must always grow and progress. We are like sharks and must keep swimming to stay alive and vital. Now in a new century how are you keeping the work fresh and vital? Particularly now that you lead a rural life and are away from the pulse and stimulation of the metropolis? Has it changed your strategy for recording visual images? Or do you recede ever deeper into a Proustian mode? In some aspects your studios have always reminded me of Mrs. Havisham's dining room.

GERARD MALANGA: I love those scenes of Miss Havisham's dining room in Great Expectations. David Lean, you know, was already a well-known and highly successful film editor in British film circles when he embarked on the making of Brief Encounter in '45 followed by Great Expectations. He had the foresight and talent to take what he learned and try his hand at making movies and he succeeded. He stayed with what he knew; and that's what I've been doing. Photographing with film is a visual language for me and I'm constantly seeing new ways of playing with the light, whether it's a building facade or the human face. I want to stick with what I know and advance within that range. I find that just seeing the nature of a digital camera you've become tethered to a computer screen. All your stuff is in this one box. I like to hold a contactsheet in my hand and scrutinize it with a lupe. I like the process of doing that. It's more tactile.

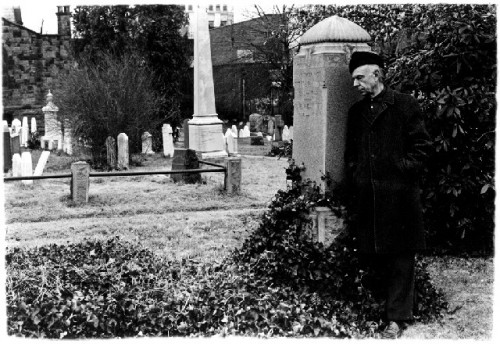

Yes, an artist must grow and progress but not at the expense of abandoning all that you've done just to be up-to-the-minute. So in this new century you're asking me how I keep the work fresh and vital, and the answer is by doing less. I have the luxury of time to get involved in organizing and disseminating my work more and that's been fun too. Environment has always played a factor in the development of my work. But you know what? Whenever I travel abroad I find myself doing the same things I would've done here. Making portraits. Photographing buildings. Empty streets. All this partly inspired by Atget, I guess.

CG: Your primary artistic identity has always been as a poet. At this point how many volumes have you published? In addition to the poetry how many other books and catalogues have you produced? You have also been involved with a lot of research projects focused on Warhol and Lou Reed. Can you give us an overview of the focus and range of your publishing activity? Typically these works have limited press runs. How many are still available and how would one find them?

GM: I think all told I've published twelve books of poetry here in the States; two each in German and French translations. I'm working with a publisher, Feather Press, in bringing out the first three issues in an ongoing fanzine entirely devoted to my work, containing a mix of poetry, interviews I've done with other artists, non-fiction, lots of photographs. The primary source for all this is, of course, Archives Malanga. To think that I'll be the first poet in America with a fanzine of my own! I like that.

I still go out from time to time to do my bit promoting Warhol's legacy, but the catch here is that I get to promote my own work as well. A couple of years back I officiated the opening of a Warhol show at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo. They even produced a special separate catalogue on my personal and artistic history which Skira brought out. Word got back to me through the grapevine that the Warhol Museum tried to kill the publication. I was slightly amused.

Last year I officiated the opening of a Warhol show at the Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary. Boy, they loved me there. My New & Selected Poems came out in 2000 and a year later, my publisher, Black Sparrow Press decided to retire, so I was left without a safety net. Black Sparrow sold its entire inventory to David Godine, so my Selected and the one previous, Mythologies of the Heart are still in print. Since that time I've been working on a book manuscript of new poems which I'm calling Someone's Life. Not my own, mind you. Everyone else's! Actually they're prose poems, one-pagers, but each line is scored like a music composition. Some lines short and some very very long within the one framework, which accounts for the stream of consciousness approach to the new work. I'm very excited by what I'm doing here because I've eliminated the personal pronoun entirely. I've completely vanished within my own work.

CG: Women and your involvement with them have been a major theme in the poetry as well as photography. Some of them have been famous beauties of their time. You have talked about "shooting a brick" or block of rolls of film during some of those nude sessions. Discuss what this genre has meant to the work. How has that changed? What is the approach as you write about and photograph women today?

GM: I don't photograph women today, at least not with their clothes off! My last nude session was in 1990 just before I moved to the Berkshires and while there I did a series of nudes with this one model in '94 which was a terrific shoot but that's it. You talk about making changes. Well around 1980, I was approached by this guy Jim Clyne who was commissioning a number of photographers to make erotic nude studies. The idea was that he would collect and edit all the material into this book which he called Exquisite Creatures. The great thing was he was supplying the models as well.

Three or four years into the project he pared down the selection and I got bumped, but I was so into the work that I continued with it until 1990 at which time I moved out of New York and the work literally came to an abrupt end. It was a very challenging experience in that what do you do once the model has removed all her clothes. What I quickly discovered was that the most erotic part of the experience was photographing the model in the act of undressing and here's where my imagination kicked in. I had them remove their own clothes and dressed them in erotic garments like white bathrobes, scarfs, mini-bras, Calvin Klein briefs, white sweatsocks.

Then I'd direct the scene like we were doing a fashion shoot, having them mimic all those gestures and poses just like the models in Vogue and Bazaar and while doing this I eased them into slowly undressing and since the clothes were not their own, there was no personal attachment involved and they could act out whatever phantasy they chose at the moment. It was like they came out of themselves. There was certainly a sense of self-discovery for the models, particularly since it was the first time any of them had ever disrobed for the camera.

Well, it got me away from doing the portraits for awhile. I was losing the spark of creativity. I needed the change. It got me into taking other kinds of pictures which only enhanced the portraits and much of everything else I'm doing now. So an additional body of work developed. Again, it's that sensibility of collecting.

CG In addition to the nude photography the women have been central to the poetry. The many great beauties that you were involved with were inspiration for poems. How has your view of women and their place in the writing changed? You have mentioned that you stopped writing about the specific muse and have evolved to a different approach and subject matter.

GM: How many times can a guy fall in love and end up writing the same poems? I was becoming an expert on the muse; or shall I say, the girl I was writing poems was getting me nowhere and it was getting to be that perhaps readers of my work were thinking that this was the only kind of life I had! Well, at the time, I was thinking no other poet was having these kinds of experience and that was neat and I certainly had my archetype in the Dante-Beatrice saga, and this was true too. Aesthetically, I was charting unexplored territory and was getting really good at it. I was reaching way down into my soul. You couldn't get any deeper! But where was it getting me? It didn't get me the girl, for sure!

Well, anyway, it's light years away from where I am now in my life and work. I find what I'm doing now much more exciting and gratifying. I'm bringing to life in a lot of instances people I'd known nothing about whom I felt needed a poem to tell their story; not mine. It's like with each poem I've gotten to know more of the person in the end from where I began. I've just started sketching in a poem about the painter, Louis Eilsheimius, but I don't know where it will take me. When I go back over these poems, these glimpses into someone's life, I hear this disembodied voice, this narrator of the narration. If only I could get David McCullough to read these poems on a CD compilation! Now that would be the perfect match!

CG Andy was known for asking people if they had any ideas. Without attribution they get into the work. With tragic consequences when Valerie Solanas shot him because she alleged that he had stolen her intellectual property. In your intimate relationship how did your ideas get used? You have told me that the cow in the wallpaper was an image you brought to the studio. Can you verify that and some of the other images and ideas? Going the other way what did you learn from Andy that found its way into your own work?

GM: Valerie Solanas shot him because she was paranoid he'd steal her movie script. If someone gave Andy something it was tossed in a pile and got lost. That happened to me a couple of times too. He was more of a hoarder than an archivist, so when Valerie phoned two or three times about her script Andy couldn't find it and then this sad and violent episode unfolded. Yes, I came up with a number of ideas for Andy's work but not once did I think of it as a collaboration because they were ideas that would be useful for him, not for me.

The Cow wallpaper idea has been re-told a few times. There was another instance when we were silkscreening the full-length Elvis portraits I suggested to Andy that we move the screen over like in a superimposition and we did this on three or four canvases, as I recall. Once it was a double superimposition; then three and then four. I'd gotten the idea from Cecil Beaton where he employed this concept photographically in a book he'd given me. So it's really in the nature of photography that brought this about. But that idea was embedded in Andy's painting of the Elvises, so it's not something I would want to claim as my own.

Back in the mid-sixties Andy purchased a Thermofax copier which he rarely ever used. It just languished in a corner somewhere in the Factory. So I started using it for my own work and ran off about 40-odd sheets of thermal paper of car crashes from my own personal stash and then typed in or wrote by hand fragments of my poetry on the open spaces. Well, back in the '70s I was dirt-poor and sold some of them to a private book dealer and then twenty years later they start surfacing as Warhol-Malanga collaborations and selling for some pretty big bucks. I immediately copyrighted the series. There's an oft-quoted remark of Allen Ginsberg's where he says "First thought. Best thought." What I learned from Andy is similarly framed. Just do it!