Southern France

Along the Foothills of the Pyrenees

By: Zeren Earls - Jan 02, 2018

Continuing on the path of curiosity to travel to places unknown to me, I ventured in late September to the foothills of the Pyrenees in southern France, then to northern Spain and Portugal on an itinerary organized by Overseas Adventure Travel. I flew overnight from Boston to Amsterdam and at the end of the six-hour flight, adjusting my watch six hours ahead, connected to another flight to Toulouse, France. Meeting up with two other tour members, I then traveled by van for another hour, arriving in the city of Carcassonne in the early afternoon.

The Hotel des Trois Couronnes, our home for three nights, was situated in the lower town, with a view of the medieval city, known as La Cité, on the hill. After a brief rest, I strolled through the streets of the lower town, arriving at the central square, the Place Carnot, which boasts an 18th-century marble masterpiece, the Fountain of Neptune. People enjoyed spending a leisurely Saturday afternoon around the fountain and at nearby outdoor cafes in the shade of plane trees.

The way back, through different side streets, revealed 17th and 18th-century buildings with sandstone facades, courtyards and gardens. At the hotel, the seven of us in the pre-trip group met over a welcome drink before attending an orientation briefing. When we dispersed for dinner, I opted for a bowl of cassoulet – a rich slow-cooked casserole of white beans and meat unique to the south of France – and then called it a day.

In the morning, we set out on a walking tour of La Cité by crossing the Pont Vieux (Old Bridge). Built in the 14th century for Carcassonne to control traffic on the River Aude, it now serves as a pedestrian bridge providing quick access from the lower town to the historic town on the hill. As we climbed the hill, the 13th-century fortress with its castle, circular towers and ring of fortifications emerged from the surrounding greenery. We entered the old city through the main Narbonne Gate, flanked by enormous towers, and strolled about the double-lined ramparts, the turreted Château Comtal and the Basilica of Saint Nazarius, a triumphant combination of Romanesque and Gothic architecture with stained-glass windows.

The residential area, which now has only about fifty permanent inhabitants, led through a complex of winding narrow streets, lined with houses with decorative features such as arched doorways and sculpted window or door casings. The medieval revival of the town has attracted small shop keepers and quaint restaurants, which cater to the many visitors. Attracted by a sign on one of these restaurants, calling itself Maison Cassoulet, I went in for another bowl of cassoulet. Then, walking downhill, I followed a scenic path from which I could see the city below, with a view of the Pyrenees on the horizon.

During free time in the afternoon, my discovery was Gambetta Square, a charming public park with statuary and benches. Across a boulevard by the park is the Museum of Fine Arts, which was enticing with its ornate Neoclassical facade. Located in a former garrison, the nine rooms of the Museum display a broad-ranging collection of European art from the 16th century to the present, grouped by period and school. I found the Museum well worth the visit, especially with the bonus of no admission charge.

In the evening we returned to the walled city for dinner, which was also an opportunity to see the city in its nighttime splendor under flood lights. Equally splendid was dinner at the Brasserie Le Donjon, which started with French onion soup served in an earthenware pot, followed by salade jambon and daube, a local version of beef bourguignon.

The next day’s trip to Albi, capital of the Tarn region north of Carcassonne on the Tarn River, offered an array of sights, including a medieval center designated as a UNESCO world heritage site. We started our exploration at the center, known as the Episcopal City, which encompasses the Old Bridge, Saint Cecilia’s Cathedral, the Palais de la Berbie (the fortified home of Albi’s archbishop), and other medieval residences.

The cathedral is a 40-meter-high, 113.5-meter-long austere Gothic edifice with soaring brick walls intercepted by long, narrow windows. The flamboyant interior offers a surprising contrast, with a rich profusion of intricately worked white stone sparkling with color. Above the central door stands Saint Cecilia, patron saint of the cathedral and of music, inviting all to sing in praise of God. The choir is lined on the outside with painted stone statues, each inscribed on the pedestal and holding a sculpted scroll with a message or prophecy. The 97-meter-long nave, with its chapels and a profusion of gold and azure in the vaulting, led us to the great organs, which are placed above massive murals of the Last Judgment, inviting contemplation through their portrayal of man’s fate.

Another church in the medieval center is the Eglise Saint-Salvy. Dating from 1270, this church, whose unique features are capitals with human figures and plant motifs, also boasts a Pietà and the bust of a woman saint carved of white stone in polychrome, characteristic of 15th-century statues.

Following a delicious lunch of duck with vegetables at a local restaurant, we ambled over to the Jardins de la Berbie. Dating from the 17th century, these formal gardens behind the Palais de la Berbie, established on the old fortifications overlooking the river and the Old Bridge, provide a beautiful setting for the medieval palace, which has been renovated as a museum to Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi’s native son (1864-1901).

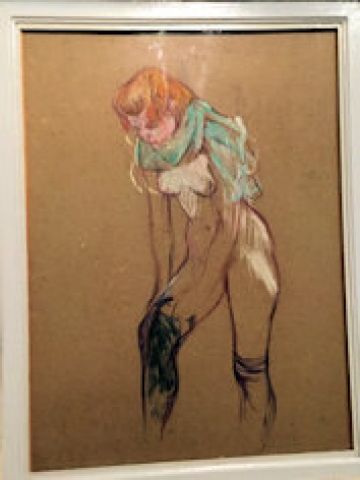

During free time, for an entrance fee of 9 euros, I enjoyed the comprehensive exhibitions in the museum, which follow Toulouse-Lautrec’s artistic development in a variety of media such as pastel and charcoal drawings, oil on canvas, and cardboard paintings and posters. Afterwards, a walk through the Market Hall provided a feast for the eye, with stalls stacked with cheese, meat, local produce, bread and a large variety of wines, all under the roof of a historic building.

On the way back to Carcassonne, we stopped over in Castres in the region of Occitania. An industrial town built at the site of a former Roman fortification and later developing around the Abbey of Saint Benedict, Castres is known for the famed Goya Museum. Founded in 1840, the museum houses France’s largest collection of Spanish art, including old masters in a former episcopal palace with an impressive formal garden. In the town center, picturesque row houses with balconies, once home to leather tanneries and textile works, overhang the River Agout, providing direct access to it at the lower level.

The following day we started off from Carcassonne, heading up toward Bayonne on the Atlantic coast. During the scenic overland trip along the Pyrenees, we stopped over in Auch, a town along the banks of the River Gers. First settled two millennia ago, it has since served as the Roman provincial capital, as well as the seat of Catholic archbishops, evidenced by the Cathedral of Sainte-Marie, thought to be one of the last Gothic cathedrals built in France. Among the masterpieces to be found inside are 18 stained-glass windows dating from the 16th century. The cathedral is on one of the Routes of Santiago de Compostela on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Now a quiet town, Auch is known for its goose liver pâté shops. We visited one, which has been a family business for forty years. Here we sampled goose liver pâté on small round slices of dark bread, accompanied by wine. The pâté was delicious, although a small jar of 350 grams of the gourmet food sold for 40-70 euros, depending on added ingredients such as sherry or butter.

After a delicious lunch at the restaurant Le Daroles, which consisted of a green salad topped with warm goat cheese, followed by a main dish of mullet and crème brûlée for dessert, we explored the town on foot. The Escalier Monumental, a split staircase of 374 steps, links the top medieval district of the town and the lower parts, which are separated by a 35-meter drop. The lower part is an area with 19th and 20th-century architecture on the opposite bank of the river.

One of the delightful stopovers of the day was by “Tour de France dans les Pyrénées”, a monumental sculpture honoring France’s annual bicycle race. Conceived by sculptor Jean-Bernard Métais, the sculpture evokes the challenging paths of the race, depicting life-size cyclists in different positions as they ride up and down the mountain.

Reaching the Atlantic port city of Bayonne toward the end of the day allowed time for a brief walk in this epicenter of the northern Basque country at the confluence of the Nive and Adour rivers. The walk included a visit to Chocolat Cazenave, an artisanal chocolate workshop and café, one of several establishments that continue the chocolate-making tradition introduced by Sephardic Jews who sailed into Bayonne fleeing the Spanish inquisition. From a menu of chocolate drinks, I chose chocolat mousseux, the house specialty, made from melted chocolate and served with crème Chantilly on the side. The velvety drink arrived in rose-patterned white cups topped with a dome of froth. At the end of a long day, the rich brew hit the spot.

The following day a walking tour of the city with a local guide helped immerse us in the culture of the Basque people, who also live in northern Spain. Euskara, the Basque language, is the last surviving descendant of the Vasconic language family, predating the arrival of Indo-European languages. To keep it alive, many dialects have been combined into one Basque language, which is taught in schools in addition to French. Before the French Revolution, the Basque people enjoyed a great degree of autonomy as successful sailors, whalers and arms makers. With the later arrival of Jewish people, chocolate-making became a staple of Basque life.

Walking through cobbled streets by narrow stone townhouses with half-timbered facades in the traditional Basque colors of red and green, we arrived at the town hall by the riverside. In addition to administration, the impressive 19th-century building, with peristyle arcades and a facade crowned by statues representing the arts, also houses the town theater. Our next stop was the Bayonne Chocolate Workshop, where we watched confectioners hand-pour, cut and package each of eleven varieties of chocolate.

In the town center is the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Sainte-Marie, which is listed by UNESCO as a world heritage site. The Gothic edifice has a large Renaissance stained-glass window, a masterpiece evoking the healing of a Canaanite’s daughter. Regrettably, some of the statues in the cathedral were defaced during the French Revolution and are on view without heads or hands. Across the river from the cathedral, the Basque Museum, housed in a 16th-century trader’s home, is a must-see cultural institution with exhibits relating to local identity, history and traditions, including folklore, religion, festivals, clothing and crafts.

Following a delicious lunch of lentil soup, fish wrapped in bacon, and fruit, we left to explore the Basque countryside. Beginning in Laressore, a rural town on the River Nive, we visited a makhila workshop to learn about the traditional craft of Basque walking canes. The process begins in the Spring with a design carved into suitable branches of a young tree, which is then left until late Fall, when the wood heels, expanding the design on its surface. The branch is then cut off, the bark stripped and the shaft straightened before being left to dry for several years. In the final stage, the stick is stained and adorned with various metal bands and fittings. The craftsman signs it and engraves the handle with the recipient’s name. Besides being a practical walking stick, these made-to-order canes are carried by hunters and hikers as a weapon for self-defense.

Continuing our countryside tour, we arrived in Espelette, a picturesque town with red peppers hanging outside of traditional Basque shops and homes. Besides the pepper-adorned building facades, the town has a castle and the ornate 16th-century church of Saint Etienne, with a beautiful Baroque altarpiece and a historic graveyard with traditional tombstones. Following a wine and cheese tasting, including a variety of chèvre and yellow cheeses, we returned to Bayonne for our final night in France.

On our way to Bilbao the following day to begin our main trip through northern Spain and Portugal, we stopped at two other seaside towns in the French Basque country, Biarritz and Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Biarritz, once a vacation spot for nobility, is a wealthy town of ocean-view high-rises, upscale shops and casinos. Our discovery walk included sandy beaches along the ocean and streets leading down to the old port.

Saint-Jean-de-Luz is an attractive historic town with coastal beaches and fishing boats in the harbor. The town’s 17th and 18th- century Baroque architecture attests to the success of Basque shippers and traders. One of these homes, built in 1643, is now a house-museum, the Maison Louis XIV, with furniture, paintings and tableware dating back 350 years. This is where Louis XIV lived at the time of his marriage to princess Maria Theresa of Spain in May 1660.

After a scenic beach walk and a visit to the bustling market, we stopped for a delicious lunch of melted brie cheese on toast, followed by baked pike with grilled tomato and rice – regrettably our last meal in France, as they were all so delicious and beautifully presented.

My parting souvenir was an elegant linen tea towel embroidered with the lauburu symbol. An ancient religious symbol with four comma-shaped heads, the lauburu today represents Basque identity, culture and unity. Having developed an appreciation for the unique culture of the Basque people, I looked forward to learning more about them, most of whom live in northern Spain, as we departed for Bilbao. (To be continued)