My Father's Portraits

Aesthetic and Psychic Legacy of Raeford LIles

By: Barbara Liles - Jan 05, 2022

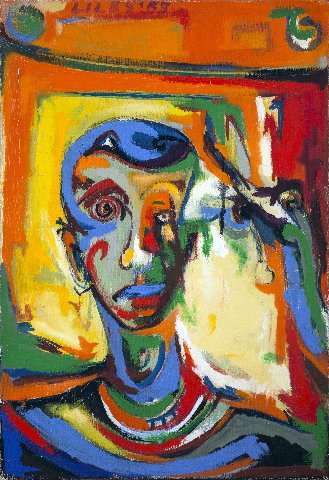

Unlike Vincent Van Gogh, who seemed addicted to selfies, my father only painted one self-portrait, in 1953, the year before I was born. If Van Gogh’s paintings with their swirling brushstrokes and brooding poses are considered indicative of his mental turmoil, then my father’s portrait is one of clear psychosis.

His eyes dominate, one a hypnotic coiled spring, the other a sad yellow Cheerio, bleeding green. A blue slash suggests a mouth and curved stripes of color embrace his neck like rings. At the side of his head lurks a detail I’ve never understood. It looks like he is being attacked by a giant insect or some strange bird is whispering in his ear.

“What is that?” I once asked.

“A pair of scissors,” he said, and nothing more.

Is that why his eye bleeds green?

Towards the end of his life, I found an old notebook in which my father’s different personalities argued about control of his eyes. If you had the eye it wouldn’ t mean you could be supreme, he wrote, it would mean a loss of something else.

When we were young, my sister, Janet, and I saw our father a few times a year. Taking the bus down from New York City, where he lived, to Washington D.C., he would escort us around the town. Those visits blur in my memory. The photos show my sister and me, smiling tightly at the camera, children for a day of a man we barely knew. It’s difficult to remember innocence. My father was sick - something to do with his head. He needed life to be simple, and being married with a family was too much. That was my mother’s explanation.

My father’s shoes were shined, his hair slicked down. He stood tall and confident, an anonymous good-looking, middle-aged man at home in a city. He hailed a cab and we slid in - it was the only time we rode in cabs. Sitting next to him, I focused on the worn leather seats, the scent of the well used car, and tried to ignore his low grunts and his body twitching next to me. Smile, nod, this was Daddy.

There was a pattern to our visits. He obviously knew nothing about children. But long before ethnic food became a fad, my father was a connoisseur. The more exotic the better. So, we always went out to eat. He chose cuisine from around the world - Japanese, Polish, Chinese - and ordered for us.

“Just trust me. If I tell you what it is, you won’t try it.”

Janet and I cozied up to bars, we sat on tatami, folding our legs under low tables. We ate octopus and sushi, sweetbreads and souffles. Looking back, I see that I considered these meals a test - was I really this man’s daughter? Somehow, I understood he was sharing a passion and it was important to be open and try everything. Squid in its own ink? Turtle soup? Softshell crabs? Don’t think about it, just eat. Even now, encountering any new food, I think of my father.

Dad bought us tacky souvenirs and awful, tasteless jewelry with our names engraved. He took tons of photos. He laughed a lot, smiled, talked to himself, would strike up a conversation with anyone.

“These are my daughters!” he’d push us forward for inspection. “They live with their mother. I don’t see them often enough.”

He took us to movies and museums. What else do you do with kids? He had no idea what parts of D.C. might be dangerous - or perhaps had a looser definition than my mother - but we often ended up in areas my mother would have never taken us. Dad was oblivious. I think, beneath a numb endurance, Janet and I were curious, even trusting. He lived in New York; he knew how to take care of us, right? I have a clear memory of one very seedy theater with Xrated “Coming Attractions.” Dad put his hands over my eyes, but I saw the pasties and naked boobs through his fingers.

My mother never asked, and we never told her.

Between visits, Dad had a habit of calling every Sunday night, like clockwork, usually smack in the middle of Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. Janet and I dutifully trudged up the stairs to the phone in the kitchen and listened to him update us about his life - he rarely asked about ours.

“Ous est vous, Ous est vous, it’s Daddy poo!”

Not much changed from week to week. He was working on a show, thinking of traveling.

“Last night I cooked a wonderful meal, oysters in Pernod. Roast them in butter, then add the Pernod. Just beautiful, beautiful.”

We listened, called him “Daddy”, laughed at his word play and jokes, which usually made no sense, “BB&T—Bacon, Lettuce and Tomato Bank”. Then we made excuses.

“We have to go.”

At some point early on Dad told us, “I’m painting a portrait of you and Janet!” He talked about the painting for months, his voice full of pride and excitement.

“I’m painting—wonderful work, good work.”

“That’s nice,” we said.

I don't think the importance of it registered, but we actually listened instead of thinking of Disney. A portrait of us. What we didn’t know was that he had not painted much in years, not since he had been hospitalized, not since our mother had divorced him. That he was still pulling himself together was lost on his children.

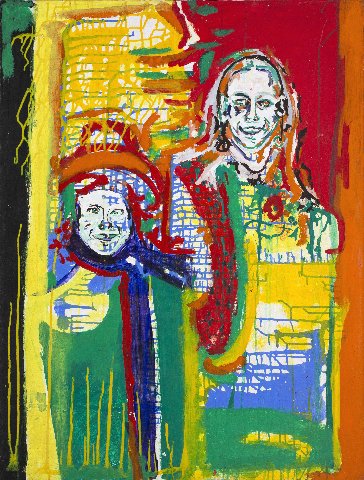

I had to ask Janet when we first saw The Sisters, I seem to have blocked out the timing. Almost life-size, more than four feet high, the painting was based on a photo from an earlier Washington visit in which I stood tall and gawky and very serious beside her. Small and pixie-like, she was wearing my father's hat.

I don’'t know what I expected, Rembrandt? Monet? Renoir’s Girl with a Watering Can? Dad had shown us modern art; I had seen Picasso’s paintings with disjointed faces, flared nostrils and skewed eyes, but I remember being shocked when I saw our portrait. Art has power, and this painting ripped through defenses I was not aware I had.

Our father had made us ugly. Floating in a bright lattice of drips and splashes of color, my face is deathly white, my eyes shadowed green and orange. He has me wearing earrings and smiling, the big Liles grin. My sister is cross-eyed and equally outrageous. She seems to be sporting a hat and scarf, though it’s hard to tell. The colors, as garishly bright as the sixties, are almost childish, and the drips speak of spills and messes. Set in this miasma of color, our faces stand out more detailed and painterly, like demonic Noh masks.

What made the painting's garishness most disturbing was the resemblance. These monsters actually looked like us: the pointy chin, the big smiles. I don’t know what we told our father; we were always so polite.

“That’s us. Sisters!”

I can imagine even smiling, a dry grin. Smile. Laugh. Patch those walls. Alone, we tried to joke about the painting, calling it “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”.

From the distance of years and some actual study of art, I can see our portrait has a certain power, a raw tension between figurative and abstract painting. I once showed it to someone who really loved it.

“Such intensity.” she said.

But it was not a portrait of her.

I tried to forget The Sisters, just as I learned to love my father from a distance. For years, there were still phone calls and occasional visits, but I chose early to be on guard. Best not get too close to that chaos.

My father had, as one psychiatrist poetically stated, “a narrow window of sanity.” He heard voices, had hallucinations, believed all sorts of paranoid conspiracy theories. One never knew what to expect. His thoughts and speech were difficult to follow, bouncing from topic to topic, often confusing and repetitive. Rational interactions only lasted so long. It was exhausting. And yet, he was also charming, very funny, often the center of attention, the life of a party, and smart enough to know he was somehow broken.

He tried to explain:

“It hurts the back of the eyes—hurts—You hear voices and they are down—they pull you down—don’'t want to kill myself, but it’s hard—in the morning when you wake up—time moves slow—the velocity of things—the brain has mass—in the morning—synapses trigger—little flash -boom—like an electric flash—a little explosion—boom, boom, boom, in memory—what I’'m trying to say —time is slow then speeds up—life is the same thing. Babies—it curves up and then you’'re old. Neutron stars are interesting. When you come out of the womb, the first thing you say is ‘waaa’—next thing is ‘why not.’’.”

Trapped in his own inner turmoil, I imagined my father as the loneliest of men. His struggles were existential. What is reality? What is sanity? What is consciousness? It could be, if you want to look at it that way, a painfully nihilistic state of mind. But somehow my father's sheer joy in living seemed to check despair. Even when he was flying towards paranoia, it was not that hard to redirect his attention, to pull him back.

“Who is the woman in this photo?”

“Where did you find this jam?”

“What a lovely color.”

My father loved life. His curiosity and sensual appreciation kept him here. He was tethered to this world with a certain tenacity, rooted in his own logic, grounded in the concrete. The taste of wild strawberries, a good meal. Wine from the south of France. The iron tang of oysters. Women. Art. Distinctions of color, a new toy, an invention, sex and money, always sex and money, held him, kept him focused. Reality needed to be verified. He wanted to be here, in this world, even as his mind betrayed him.

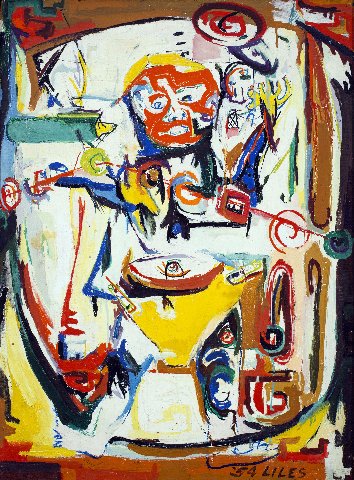

My father painted a portrait of me as a baby. In my memory of this painting, I am screaming, but looking again at the real thing, the infant’s facial expression is almost placid, a bit confused, questioning. What’s up Daddy? No gaping, screaming mouth. But the face is red, very red, the eyes are crossed, and a yellow claw waves or perhaps blindly grasps at air.

Lines and patterns, disjointed swirls of color camouflage the subject. A baby. With a bit of effort, the rest of Me comes into focus, a yellow diaper, a foot, a belly button, a bottle. Peering closely, there are even safety pins. I think I am in some sort of baby seat with toys hanging above, though it also looks as if I am floating in a white bubble. Having had children, I recognize the point of view, looking down at an infant—helpless and needing you—they are yours and they are aliens at the same time.

Here I look like the devil’s spawn.

I was over 50 fifty years old when I first saw this portrait. I didn’t even know it existed. Still, when I saw the date, 1954, I knew. This devil child was me! By then, I understood that my father was an abstract painter who did not truck in beauty, but it was still hard not to be hurt. Most of the paintings I know of infants are from the Renaissance. Pink cherubs and baby Jesus are perfect, they do not wear diapers or have red faces and never cry. I was definitely not a holy child.

The Baby was painted when my father was thirty-one years old, living with my mother in France. The youngest of four brothers, an ambitious braggart, he had been a young fighter pilot in WWII. Trained as an engineer, but interested in art, he took advantage of the GI bill to leave Alabama and study with Fernand Leger in Paris. My mother encouraged his exodus. After the money ran out, my parents found jobs with the military and stayed on as expats. My father painted, had a few shows, my mother worked, they ate and drank, had friends. I was born in Paris. It sounds romantic, but less than three years after he painted my baby portrait, my father had a major psychotic breakdown. We would never live with him again.

Does my father’s mental fragility show in his paintings? The color, the chaotic brushstrokes, the content, are less disturbing than most modern artists, but there is a riotous energy, a dissidence that is difficult to ignore. Always so ready to take the blame, I used to wonder if my birth, my purported crying, pushed him into crisis. Later in life, seeing him a few times a year, he would often go on about his “crooked seed” and how he hoped he hadn’t passed it on. Does his fear show in his portrait of me, his first child?

I admire my father’s paintings. He had talent. You can feel the emotion splayed across canvas and drink in his love of color. A “figurative abstract expressionist” is how he described himself, yet he fit in no box, which may be part of the reason he never had much success. That and the reality that he was mentally ill, a man with shadows, heavily medicated, yet gregarious, magnetic, a little scary, the life of his frangible party.

Dad was having quite a party when Virginia, his third wife, called and asked for help.

“Your father is having some money issues.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. She had never requested help before.

She paused as if she didn't want to tell me, then, in her soft southern voice said, “He's writing a lot of large checks and ordering things with credit cards.” She couldn't keep track. He wouldn't listen to her. She would pay for me to come.

I don't know what I thought I could do, but I'm a sucker for being needed.

I flew to Birmingham, Alabama, where he and Virginia had recently retired after a lifetime in New York City, and found my father vibrating as he raced into mania.

Now in his eighties, my father had lost weight and wasn’t paying attention to his looks. He wore an old leisure suit, which I am not sure he changed very often, his hair was barely combed. The twitches I remembered as a child were back, his movements jerky, an ancient robot. He stuttered and shuffled. No eye contact. Of course he was drinking.

Dad had commandeered the large back bedroom as his studio and the walls were covered three high with his paintings; most of them I had not seen, as many from his time in France had been in storage. That’s when I first saw The Baby.

“Dad, is that me?”

Seeing it, recognizing myself, I was overwhelmed with a sense of loss, the father I might have had, the artist he could have been, the crapshoot of karma and mental illness. 1954—almost fifty years of trying to reconcile my feelings towards my father and I could still be blindsided.

For most of my adult life I had seen him sporadically, but never like this, manic, psychotic—having an “episode”, though perhaps I hadn’t paid attention, willing to accept Dad as a slightly eccentric uncle. He had always been so suave, so good at passing for almost sane.

Now I followed him. There were hardly any sidewalks, but that didn’t bother him. He walked in the street and waved cars around, swinging his arm wildly, as he loped along like an overly animated traffic cop. I could barely keep up.

Everyone seemed to know him, happy to have such an enthusiastic customer. The bookstore, the jewelry shop, and especially Do Di Yos, an upscale restaurant/store, where he was buying bottles of wine by the dozen, though his doctor had told him not to drink. The spending was amazing, his second wife had had some money. My usually frugal father had hundreds of dollars flying out of his pockets.

I tried to be understanding, reasonable, as I listened to him rant obsessively about investing.

“We’re not making enough - the bank. Gold, we should buy gold.”

He wanted to play the stock market, insisting he could not lose money because “you can get insurance for seven dollars. No losses! No losses! We can make millions, buy houses in Florida at auctions, rent them.”

It was MONEY, Money, money and it was terrifying. Dad was ordering steaks and jewelry, gold and silver online, cleaning out all his accounts. He had multiple credit cards; as soon as Virginia found one and tried to close it, he opened another. He was barely sleeping and stayed up late ordering things from the Home Shopping Network. Packages arrived daily.

“Dad, you can’t keep spending like this,” I sounded like such a parent.

“It's my money!” He sputtered and yelled with an energy that was actually scary.

A day later, when caught sneaking bags of wine bottles into the apartment, he broke down and cried, “I have a problem, I have a problem, I’m sick, I’m sick.” Hugging his bony frame close, smelling the sour scent of him, I felt a rush of affection and, to be honest, a bit proud of myself. By the afternoon, he was circling real estate ads with a Sharpie and wanted to go to a pPawn shop to sell some gold coins.

Much to our surprise, Dad outlived Virginia though she was a few years older. When he needed help, my sister and I came. We packed and cleaned and moved him, we visited him in hospitals, managed his finances and knew his list of meds. We answered calls at midnight and three in the morning.

“No, they are not coming to get you. They don’t want to harvest your alcoholic liver.”

It became clear to me that my father was my first child.

Years after Virginia died, while visiting my father at his assisted living facility in Alabama, I took a day and drove a few hours to the VA Hospital in Tuscaloosa. A huge facility of brick and lawns on the edge of town, this was where my father had been committed after his breakdown in 1957. I didn’t expect much, it had been almost sixty years, but I wanted to see the place that was so pivotal in his story and make it real.

Arriving on a Wednesday close to noon, I found the PR director who found a doctor, who had been at the hospital for a long time. I gave them a truncated account of my father’s life. Pilot in the war, artist in France, breakdown, divorce, disability pension, artist in NY, three wives, still alive at ninety-four.

The doctor, a woman with large eyes and wrinkles she did not try to hide, surprised me by saying, “Good for him.”

“I just want to see where he was.” I explained.

“He would have been in building thirty-nine or forty. Those were the locked wards.”

“He had insulin shock treatment,” I said. I had ordered his medical records.

The doctor nodded. “He would have seen other treatments too. Lobotomies were done in surgery.” She mentioned this casually, then looked at the PR guy—as if expecting him to deny it.

“That was what was being done back then.”

That hit me. My father had probably seen people in worse shape than himself. No wonder he was so proud of getting out alive with whatever brain he had.

I wandered the grounds and found building # thirty-nine—a nondescript single- story brick building, it now housed offices and looked like it would be stuffy in an Alabama summer. He had arrived in August, just after his thirty-fourth birthday.

When first pressed, my mother said she didn't take us to see my father. It would be too disturbing. Later, she remembered taking us once and having a picnic with him on the lawn.

“It must have been fall,” she said. “The leaves were down, but it was warm, and the sun was shining.”

I would have been three and a half, Janet, less than a year old. We had not seen our father since we left Paris months before, moving, running. My mother hints at violence. My father liked to brag, “the butcher knife’s still stuck in that door.”

Did I run to him and throw my arms around him or did I hold back, shy and awkward? My mother says he was drugged and zombie-like, smiling, but not himself. She did not bring us again.

I have never really wanted to travel in time. But that moment intrigues me. What did she tell us then? Daddy's sick. Daddy's sick. That's what stuck.

He was crazier more paranoid near the end, in and out of Geri-psych wards. The dogs were coming in the night and THEY were trying to poison him.

“The Chinese Mafia wants my DNA.”

What calmed him was making art. No Bingo for him. Color was his tranquilizer of choice; he created with a focused intensity.

“That’s when he was able to enter the eye of his storm,” says my sister.

Much to the chagrin of the cleaning crew, he splashed paint everywhere. Old paintings bought at thrift stores became new canvases. Somehow, he procured cans of spray paint which were quickly taken away; he was already on oxygen. He had plans for a show. Plans for a new series. Plans to sell his work on the internet.

Dad painted even as he declined, from assisted living to skilled nursing. With the help of aides, his hands shaking, his eyesight failing, he painted and drew abstract lines of color, choosing one to lay against another, hot and cold, curving the lines just so. Pointing to the next marker, “Blue, no light blue.”

He died a month shy of ninety-five, a mental health success story, skewing graphs, blowing all the stats, especially for those with mental illness—the suicides, the drugs, the bullets during a crisis. By then he was pickled. Between the early insulin shock treatments, the sixty years of psychiatric meds, and the self-medication of alcohol, lots of alcohol, it's a wonder that he lived so long. But he did and well. A backstreet boy from Birmingham, he graduated from college, traveled the world, had two children, three wives, friends, girlfriends, and his career as an artist—not your stressful nine-to-five job in an office with a boss career, but better still, a focused vocation, an identity.

Though much of the time he lived beyond the boundaries of what we call sanity, my father found a way to live in this world with humor and some grace. His priorities seemed to be to enjoy life and to avoid being hospitalized again, a careful balancing act supported by friends and strangers, wives and daughters, a disability pension, lots of meds and sometimes pure luck.

My father was an artist. His life’s work, his emotion, his vision, his color, his discipline and energy is stacked in my sister’s basement. Since his death we have photographed and cataloged hundreds of paintings, moved them multiple places. I have spent more time with his work and know it better than I ever did the man. Sometimes, studying a painting, I can almost imagine his state of mind, why he chose a particular blue or swept his brush like a wave in the Loire. Much of the time I am baffled and amazed. A pigeon on a head? War medic? Hands turned to blood? I want to understand.

The Baby is there in my sister’s basement and his Self-Portrait, encased in bubble-wrap. And The Sisters. It has been more than fifty years since he painted The Sisters, and I am still wrestling with it. I do not want it on my walls; I find it too disturbing, too full of conflicted memories and feelings, of confusion and expectation, of heartache and love.

As any portrait, The Sisters captures both the subject and artist in time. I am ten again and my father, forty-one. I wanted a father who loved me. I wanted a father who didn’t twitch and say scary things, who made sense at least most of the time. I wanted so much. And my father? Who knows? After some difficult years, he had finally found a way to live in this world as an artist; the act of creation grounded him, gave him purpose.

The Sisters was the first figurative work my father painted since his time in Paris, since his hospitalization almost seven years before. I like to console myself by thinking that it was my sister and I who brought our father back to painting—anchors in a sea of color, perhaps a sea of madness. It is our faces in that portrait that are the focus within chaos; we carry weight. I may be reading in meanings, but isn’t that part of the wonder of art?

My father painted a portrait of his daughters. I shy from the heartache and rest awhile in the knowledge that he thought of us drenched in color.