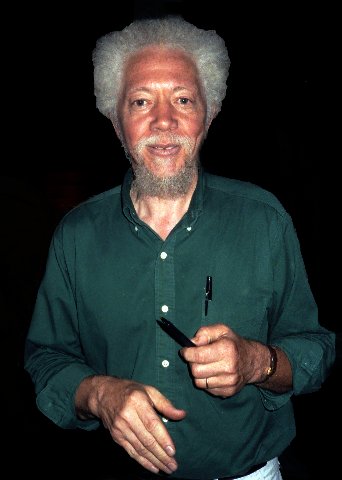

Artist Activist Benny Andrews

From Georgia Sharecropper's Son To NEA Administrator

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 05, 2025

He was born in a family of ten, the son of sharecroppers in Plainview, Georgia. His father, George, was a renowned self-taught artist. While needed for labor, his parents encouraged education and he graduated from high school. He received a two-year scholarship to go to Fort Valley College, a Black state college in Georgia. He joined the Air Force and served as a staff sergeant in Korea. After four years in the military, he attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on the GI Bill.

In 1958, he moved to New York where his exhibitions were praised and led to awards and fellowships, including several residencies at MacDowell, where he joined the board in 1987. Early on he summered and exhibited in Provincetown.

Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) in 1969, an organization that protested the Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. No African-Americans had been involved in organizing the show, and it contained no art—only photo reproductions and copies of newspaper articles about Harlem. The BECC then persuaded the Whitney Museum to launch a similar exhibition of African American artists, but later felt compelled to boycott the Whitney show for similar reasons.

From 1982 to 1984, Andrews served as the director of visual arts for the National Endowment for the Arts. In this position, he had the chance to advocate for fellowships and grants to go to talented Black artists.

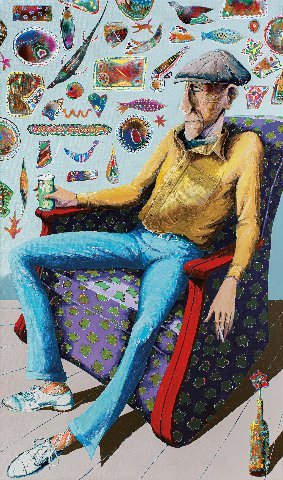

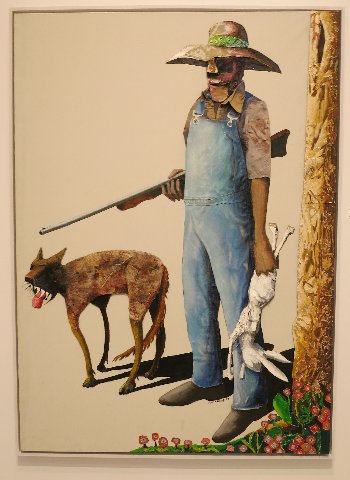

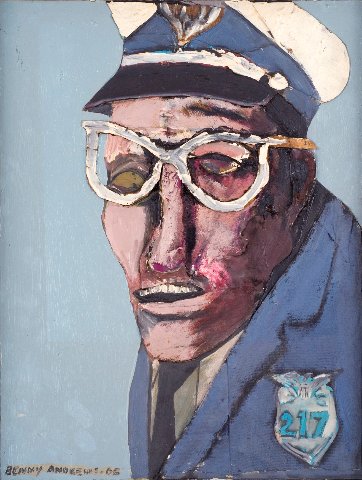

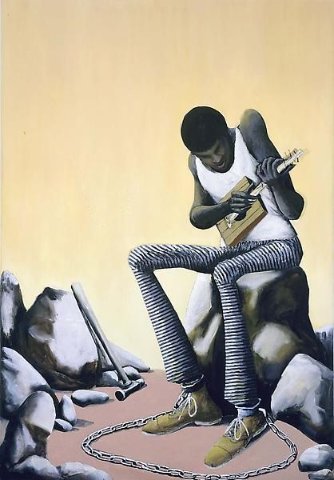

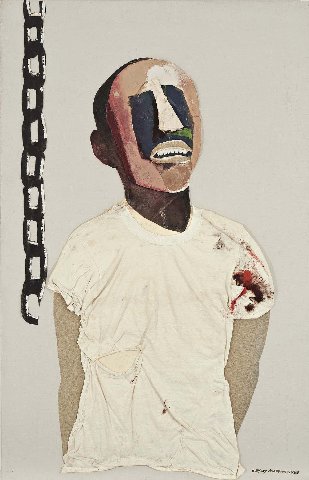

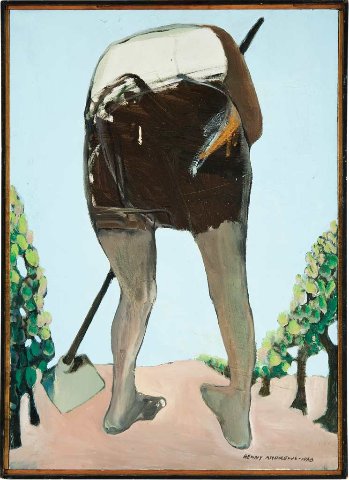

There were collaged elements in his paintings in the figurative expressionist style which developed among the Sun Gallery artists in Provincetown. We met as dinner guests and initiated an ongoing dialogue. With the support of Ellen O’Donnell, then director of the Provincetown Art Association, I curated Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emilio Cruz, Bob Thompson, and Earl Pilgrim. It traveled to Northeastern University. The curatorial essay was published by Provincetown Arts Magazine. The Andrews estate is represented by Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York.

Interview with Benny Andrews

1980s

At his New York Studio

Benny Andrews (1930–2006) A heavy social problem is obvious and conscious for Black artists, or anyone Black, to deal with representational things. So, a lot of the ways you say things, it would be a lot easier and understandable to deal with the figure. Being abstract means bringing something else to it.

Even Sam Gilliam (1933–2022), when he talks about his work, talks about representational things, Mississippi and stuff like that. For most of us, what we are working is a natural extension of us. In a sense it’s unfortunate because it (Gilliam’s work for example) is a luxury we cannot afford. I’m not talking individually but as a group. Black artists are not looked at for anything that they do other than representation. We’re pigeonholed.

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) is the best example. He would be put into exhibitions and that would integrate them. If his work wasn’t representative of something identified as Black figures, he wouldn’t have served that purpose because of just blending in. If he had been an abstract expressionist, what good would it have done for curators to have him in there, for the general public too, but you at least have one.

Charles Giuliano The intent is not just to include a Black artist, but one that clearly reads as Black.

BA I had an experience that a lot of people had in the 1960s. At first, by and large, nobody was interested in the Black people I did. I started to show at Forum Gallery with exhibitions in ’62, ’64, and ’66. All along, I have depicted both Black and White people. Nobody was interested in the Black people. Black awareness evolved in the mid-1960s and (then) nobody was interested in the White people I did. They would come to my studio and pick all the Black people, but they weren’t interested in my White people because they were trying to make a point about Black people and Black art. There was an irony that what remained in the studio was the exact opposite of what was being shown. In the exhibition there were all the Black people, and in the studio, what remained, were all the White people. That’s an example of when social consciousness outweighs whether the work is good or bad. That’s an underlying problem for most Black artists.

It’s the same in theater. The presence of a Black actor on stage has to be dealt with. Do you want to put two Black actors out there or have an all-Black cast? That starts playing around with the question of quality. Is that person the best actor, dancer, or artist? Are you dealing with quotas in one way or another? That plagues the artists.

Often, they come in and like the other work. They like (images of) my father who is nearly White, but it wouldn’t serve a purpose to show that. They would take a painting of my mother because she is so Black that it would serve their purpose. If they like the painting of my father, but don’t take it, that’s racism.

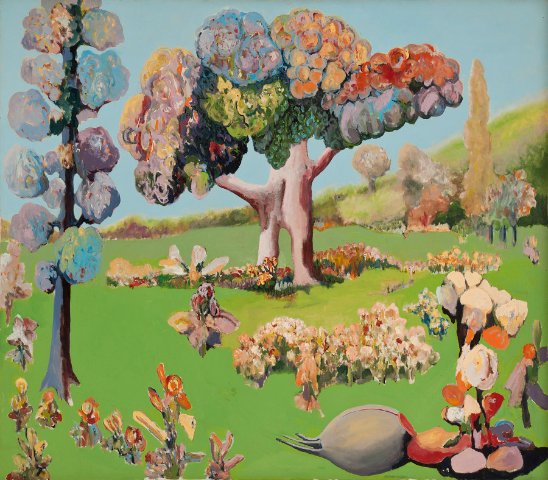

When people come to the studio they’re not interested in my landscapes. That’s not what they have in mind for representation in a show. That’s changed a lot as people have gotten to know my name. I have a show called Completing the Circle where I finish the monuments in Washington D.C. There’s the George Washington Monument which extends from the Capitol. When I studied (Pierre “Peter” Charles) L’Enfant’s (1754–1825) plan for Washington D.C., I learned that he had a plan for a circle, so I designed three other monuments. One for the struggle of the country, another for beauty, and a third that I can’t remember right now. There has been a lot of interest in the show, which is traveling right now. When exhibitors found out, they wanted a show of Benny Andrews the Black artist in their museums and exhibition schedules to have a Black artist. The show includes maquettes and drawings through my conceptual interpretation. I do what I want to do.

Consider Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) and people like him. In retrospect they became collectable, but they don’t serve the long-term purposes of people who are talking about Black artists. What Tanner was showing was that he was an artist. He incorporated being Black in some of his work, which is a healthy thing.

CG The painting we all remember is The Banjo Lesson. If you visit the Philadelphia Museum you encounter Tanner as a brilliant student of Eakins.

BA It doesn’t satisfy that need. In the case of Horace Pippin (1888–1946) some of his works are fantastical representations of race, but in other works he goes into something else. Pippin was known and collected for a long time with nothing to do with being Black, which is as it should be.

When it comes to the general public, there are needs to serve certain quotas, and unless that individual represents that quota in a certain way, he doesn’t qualify. You know, when we are talking about the figure. I like to do the figure.

CG In curating this show Kind of Blue, I have dealt extensively with Black artists through a career of covering jazz, rock, and blues. I have been involved extensively with Black culture as a critic, teacher, and record collector. But prior to this show I have not dealt with Black visual culture on a professional basis. It strikes me that a lot of Black shows in museums have been curated more from a political than cultural basis. For this show I find it challenging to work apolitically and feel no pressure other than to create an outstanding exhibition.

BA Prior to the show that Barry Gaither organized for the MFA (African American Artists; New York and Boston included 158 works by 70 Black artists, May 19 to June 23, 1970.) they had never before done any such shows. It’s like when the Metropolitan Club let Jews in for the first time. What happens when it’s for the first time is totally different from what happens when it’s a routine thing.

CG What has happened now that the political pressure that spawned those shows has subsided?

BA For me, it was not just restricted to Black artists. It’s something that happened all over the country and throughout society. It created a climate in this country where other non-traditional groups were included in the cultural arena.

You have to exclude entertainment because even when people were in chains, they were allowed to travel in minstrel shows to entertain White people. They would make things funny, like court jesters. You can look at the entire white entertainment industry and compare it to the entire world of painting and sculpture and it doesn’t hold anything. It’s nowhere near it. When you talk about Sinatra and Prince, the entertainment business, then turn around and talk about artists and museums, well they are just nothing. The entertainment industry represents billions. Then you look at Frank Stella and other leading artists, the general public has no idea who they are. They may know about Warhol if it has to do with fashion. But there are no artists who are really well known. Maybe Andrew Wyeth.

CG Because the entertainment industry is a business, you can quantify it. You can see how a music release charts in Billboard or the box office for Hollywood and Broadway. It’s possible to compare critical reviews and how the product sells. There is no such information in the fine arts. We don’t know what shows are selling in galleries. Is Stella, for example, in the top ten this week, or has he dropped? What about Benny Andrews charting at 78 with a bullet? The art world is remote and inaccessible. The public has no access to information or its influence. Only a handful of individuals are capable of purchasing work and influencing an artist’s career. That’s in the hands of a few influencers, which makes them more important in establishing matters of aesthetics and taste than they should be. At the academic level, movements and individual artists are not evaluated. There is no dialogue about why Pollock, for example, is more important and influential than Motherwell. Museums do not disclose what works in their collections are worth. There is an academic lie that all work is equal. Which is not true, of course, for the collectors who buy from galleries and auctions. Then we see the real dollar value of the work, which is never discussed in the classroom. In the teaching of art history, all movements and individual artists are treated as equal. The introduction of feminism has further flattened the canon. In the new textbooks Judith Leyster gets equal billing with Rembrandt and Vermeer.

BA To the general public. the art world is insignificant. For us, it’s pretty big. We are impressed because we are a part of it. People in the poetry world are impressed though the public could care less. In the real world, nobody knows any poets. In the entertainment world, if you ask people who they like, there are ready answers. I’m saying this to put into perspective a show like the MFA’s African American Artists: New York and Boston. In the enclave of the art world, it was the first time that happened. It didn’t matter what happened compared to the fact of Black people coming to an opening and drinking out of tea cups that was unique. To come as guests and not as servers was a phenomenon. It was a breakdown of segregation and so much more than just an exhibition. Before they had the first woman on a space shuttle there was never a conversation of where she was going to go to the bathroom. It wasn’t an issue until she went and I don’t know what they did. Until things happen you don’t have a problem. The MFA didn’t have a problem of what to do with Black people who are guests at an exhibition

CG Did Black people visit those shows?

BA They came in droves. But the Met was a fiasco. Not many Black people visited Harlem on My Mind. It wasn’t something that Black people were interested in. It didn’t reflect them in the way that they felt they should be. A lot of White people went because it was kind of an exposition. It was something that should have taken place at the coliseum. It was like a trade show. The same was true about the one that took place at the Whitney, about which there was so much controversy, because we worked with them on that show and then they reneged on it. Of course, the MFA show was the definitive one of its kind and the public attended in droves. It’s a historical show in that it occurred at that venue at that time with input from Black people. It was the only one at that time with Black input.

CG Were you involved with the selection?

BA At a distance. It was Barry Gaither who made the selection. At the Whitney there was no Black involvement. They had no Black people they were able to consult with. The Black historians they claimed on the brochure were not consulted. So, there was no Black input for the show. The MFA show was the only one at that time with Black input. You were asking about the status of Black artists today. That goes with all the pluses and minuses of society. There has been a transition of attitude.

Black people who have been included are doing well and that includes artists. The ones that are still out, and that’s the largest group, are still having a hard time. The pressure that created the MFA show no longer exists.

CG That’s part of why I want to do a Provincetown show, because there is no pressure to do it other than to curate a compelling exhibition which says something about Black artists in Provincetown.

BA That’s the plus and there are more of these shows. More people are interested in what you are saying about the aesthetics or dramatics. That’s healthy and how it should be. It’s like poor people. It’s understood that people should eat better. But a lot of people are eliminated from getting food, which is a bad thing. That’s what’s happening with artists and not just black artists. There’s a stronger emphasis on financial and critical success. People are getting the rewards. We are seeing it happen in Soho and the East Village. It’s happening for a few Black artists. But there’s less effort being made to assist artists in areas like alternative spaces where artists don’t have to prove that they are trying to be successful.

(On April 6, 1971, Grace Glueck reported in the New York Times. “Fifteen black artists out of a scheduled 75 have withdrawn from the Whitney Museum exhibition, Contemporary Black Artists in America, opening today. Their action is in sympathy with a boycott called by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, a group of black artists that initiated the show nearly two years ago.

“The Coalition, which claims an active membership of over 150, charges that the Whitney reneged on “two fundamental points of agreement”—that the exhibition would be selected with the assistance of black art specialists, and that it would be presented ‘during the most prestigious period of the 1970–71 art season.’

“At a press conference called by the Coalition at the Studio Museum in Harlem yesterday, a number of black art specialists from across the country issued a supporting statement. It demanded, among other things, that ‘black art experts and consultants and/or institutions must be involved in the preparation and presentation of all art activities presented by white institutions and involving the black artist and the black community.’

“A separate statement issued by Cliff Joseph, co?chairman with Benny Andrews of the Coalition, said in part that in order for the show to have authenticity, ‘it is essential that it be selected by one whose wisdom, strength, and depth of sensitivity regarding black art is drawn from the well of his own black experience.’ The show was organized by a white curator, Robert M. Doty.

“Yesterday John I. H. Baur, director of the Whitney, said he had a basic philosophical difference with the sentiments expressed by Mr. Joseph. ‘It’s more than a matter of our wanting to take full charge of our own show,’ he noted. ‘The Coalition stands for a kind of separatism I don’t believe in. The black artists don’t have backgrounds in tribal art—they’re part of the American experience. And they should be judged by the same yardstick as other American artists.’ ”)

CG What’s happening to organizations like the Studio Museum of Harlem or African American Artists in Residence Program at Northeastern University?

BA That bears out what I am saying. The Studio Museum is doing fantastic. It’s the nation’s foremost Black cultural organization. Other kinds of organizations that would have helped are dying on the vine. There is adequate. if not plentiful, support for the Studio Museum. It has raised itself by its bootstraps to become a first-class institution.

CG Give me some other examples.

BA There’s Barry Gaither’s National Center for African American Artists in Boston.

CG It has very low visibility.

BA It suffers what Boston suffers on a lesser scale. The Studio Museum benefits from what happens in the New York art world. The National Museum suffers in that sense. The MFA and ICA get a certain amount of publicity but a fraction for that of the Met and New York museums.

CG Are there other institutions around the country?

BA There is the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center. It’s named for the Black French pioneer who established what became Chicago. I believe he was a fur trader. In Philadelphia, there’s the Museum of Afro American Art and Science.

The museum in Chicago is funded by the city, as is the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s a success because it receives a certain amount of public funding, as does the Studio Museum. So, it is not existing hand-to-mouth. There’s an Afro American Museum in Los Angeles which was built by the state. It was legislated into the state budget. The institutions which I mention are the only substantial ones that are mostly oriented to the high arts.

The rest of the organizations are like AAMARP which has survived because of the support of Northeastern University. (Which is no longer the case.) Artists spaces, if they exist, would be like PS1 and things like it but they are almost nonexistent.

CG Is this Reaganomics?

BA Reaganomics have played a part. He and his staff are reflecting on what the people want. There hasn’t been any attempt to impeach him. The voting population is quite happy with Reagan. He and his people are the mechanics for this because it is what the country has wanted. Look at what’s happening with food stamps and social security. Roosevelt didn’t make social change by himself. There was a demand in society for social security. We’re in an era of survival of the fittest for society. The poor and unfortunate are being shunted aside. It’s happening to Black artists as well.

CG Is that what you felt in Washington, D. C. at the National Endowment for the arts? (Andrews taught art at Queens College for three decades, and from 1982 to 1984, served as the Director of the Visual Arts Program for the National Endowment for the Arts.)

BA I was trying to level out fairness with distribution all over the country. That was a different approach. Utah and Maine were being looked at for what they were doing. We tried to get more of them involved in making decisions reflecting what they saw instead of having one group decide what everyone saw. You have New York people deciding for a Georgia or Texas person. That this is Georgia or this is Texas. Or, this is not Georgia or this is not Texas.

I was trying to get more involvement of experts and people who were trained in those areas, who had an affinity for what they were about or not about. I tried to encourage more tax payers’ money to go to diverse places.

CG Did that agenda succeed?

BA Yes, very well.

CG How did that impact you with your New York friends?

BA It was never written about in any art publications. I was never mentioned. It was seen as anti-New York to do something like that. When I was there it was never mentioned in newspapers or magazines. They didn’t mention me because I was attempting to make a more democratic NEA.

CG You were not interested in rewarding the already established and celebrated.

BA I was not the only one but I was trying to get more and more people from all over the country to speak and talk. The jurors were trying to see that more of an experimental nature would be done in areas where this would not normally happen.

CG Still the best artists move to New York.

BA That’s changing because it’s no longer possible to come to the city and find an affordable loft. It’s very hard to live here but that’s another thing.

CG Are more artists staying home?

BA They are trying to or going to other areas. There’s coming to be more and more support. When they said that about Paris it wasn’t true. Artists went to Paris because it was the best place to get attention for their work. But when America progressed socially and economically people developed art here in New York. People started to come here. Now there are a large number of people moving South because there are jobs there. They used to come here for jobs. In the arts you have to go where you have the best chance to survive. It’s not just being an artist, it’s to find a place to survive and create.

Right now, New York is so expensive that it’s almost an impossible place to live. When they are starting out artists need cheap space to live in order to survive. If you can’t find that there’s no way to be an artist.

CG A couple of years ago I visited Skowhegan School (in Maine). Art critic Hilton Kramer happened to be in residence. I attended an informal session with students. He fielded questions including how important it was to live in New York. He responded that they would never be successful artists unless they lived in New York as that is the center of the international art world at this time.

BA Kramer plays an interesting game. That makes him very appealing as a lecturer. We’re on the same circuit and have had some interesting debates. It’s set up like throwing red meat to hungry lions. People know it’s not the truth but can’t argue against it because he has all the right credentials. There are art world powers.

It’s like the Metropolitan Club with fat cats sitting in huge chairs. They have the money and power. They guard the doors that lead to opportunities. They’re not right because out in the street other things are happening that they can’t control. If you look at the art world there are the heavy hitters and gallerists like Leo Castelli and Mary Boone. In criticism there’s Kramer, Grace Gleuck, John Canaday, and John Russell. They greatly influence things for the general public. Robert Hughes tries to see it differently. Because he writes for Time he has a larger audience with a great advantage and can knock them. It’s like Boston playing LA. They are both winning a lot and making money. When you think about it. the power brokers are all millionaires. Hughes is doing this with Kramer and Kramer is doing it with whoever.

CG Clash of the Titans.

BA That’s right. What does it matter if Ali beats Frazier? That’s what we’ve got on a small scale because the art world is so insignificant.

CG As someone who has served in the NEA, what would you say to a young artist other than go to New York and find a loft?

BA None of us are at the stage where we can tell others exactly what is good or bad. But the basic thing for anyone aspiring to be an artist is that you are doing the work and want to be an artist. Trying to be one should be your primary goal. If you find a way to do that, you’re successful and you should see that just being that is a success. Anything beyond that is at the mercy of fate.

Be it Hilton Kramer saying you have to come to New York, or, someone else saying that these people should have a chance; things that sell and things that don’t sell. You have these problems and they are a part of the profession.

It’s like being a cab driver who has problems with wrecks and flats. If someone tells you to go to the barn and pick up a cab be prepared for what it entails. You can’t start complaining about the issues. You won’t even get to start the ignition, which is your mission as a cab driver. A great many individuals set out to be cab drivers and succeed. They don’t become famous like movie stars. They don’t meet producers who put them into movies. That happens once in a very great while.

It’s the same with people aspiring to be artists. The problem with discussion of insidious plots and schemes is that they have nothing to do with making art for the vast majority of artists. It’s like gossip of the Tylenol scare (1982). It killed ten people but all of us were involved. It’s like when Leo Castelli shows up at Sotheby’s and buys something or sells a Johns for $2 million. Or Andy Warhol wears a tuxedo backwards at an event. All that has nothing to do with being an artist. It has nothing to do with me and my work. It doesn’t impact my art, possibilities, or opportunities.

That’s the problem when you start talking about what Hughes said, or Kramer said, or what Castelli and Mary Boone said. It has nothing to do with being an artist.

CG If you have a speaking engagement in Iowa or Wisconsin, and visit students and artists, is what they are making reflective of what they have seen in art magazines? Young artists tend to take very seriously the influencers you have mentioned.

BA For a young person trying to be creative whatever is going on is by and large over. If you know about it in Wisconsin it’s over by the time you get the news. It’s like yesterday’s paper. If you learn about Keith Haring or Neo Geo, by the time you learn about it, then it’s too late to work in that manner. It’s been done.

CG That’s what’s wrong with art schools. Instructors get hired when they have established careers. With that security and tenure there is less pressure to develop new ideas and work. They pass on their outdated approach to students. My professors taught social realism and abstract expressionism in the 1960s when Pop, Op, Minimalism, Conceptualism were emerging. What we were taught was outdated. That’s the plague of art schools. Very few of my colleagues are still trying to develop and exhibit.

By that standard are you over?

BA No, I am talking about being influenced. When I was a student (Art Institute of Chicago), we would be getting material from MoMA or what have you roughly a year late by the time they put the show together. It was over. That’s what I would tell students. When it comes to (David) Salle or (Julian) Schnabel that’s ok to read about but has nothing to do with your own creativity. You can’t try to do something in that manner.

CG During the 1960s during Spring break I visited New York museums and galleries. I went to the Cedar Tavern expecting to find artists. It was just a bar. I had a beer then left.

What is the current status of Black art?

BA I don’t accept that there is quote “Black Art.” Not in the way that you or we are talking about it. Now if we talked about Voodooism. Or if you talked about Africa in the context of the art of Africa. Or if you wanted to slash and say Africa/Black. I think you could generalize a lot more about Africa or Black art. Unless an individual is kept in a barrel or down in a well it is impossible for him or her not to be affected by what the country is. It would be like saying Polish Art or Irish Art or Jewish Art. Of course. there are things that the Jewish people, if they are concerned about it, they can affect the way things are done. There can be Yiddish Theater, Ben Zion, or Chaim Gross. They do things that stem from a Jewish or Hebrew basis.

That distinguishes it from what a Sean O’Casey would do on an Irish basis. Nobody pigeonholes his as “Irish Writing.” They talk a lot about Irish writers that write and give it a lot of room. It can be romantic, social, or abstract. You can talk about French writers or American writers. You can talk about Black writers in America or talk about Black painters in America. But if you expect that when a Black person creates a work of art, and you come to it expecting to see Black art, that’s asking to see too much. There are a lot of Irish writers who don’t write in such a manner that you can distinguish them from a Scottish, Welsh, or English writer.

CG What about Jean Michel Basquiat (1960–1988)?

BA I’m not really critical of him. I think it’s fair that he gets what he gets. But it is a typical thing in America that he is not, in the eyes of those who make the decisions, an Afro-American artist. He comes from an island and things like that. And that’s been the history of acceptance in the United States. It is much easier for White people to accept people from other areas. People who, in their eyes, did not come from slavery. That’s the logical thing.

When they did the Conflict and Controversy show at the Studio Museum, they selected work from the decade 1960–1970 when there really was a social thing at that time. As a gesture the New York Times put Basquiat on the cover of its Sunday Magazine. They simply would not deal with any of the African-American artists in the exhibition because they just can’t handle that. But exotica they can handle and chose someone like him. He reflects the living style of that magazine. He dresses in a manner similar to styles advertised in the magazine. It’s a classic example. The social implications of putting a Dana Chandler (Born 1941, an artist activist who founded AAMARP at Northeastern University) on the cover, or even in the magazine, was too much for them. Basquiat had nothing to do with that decade. He wasn’t even working then.

CG So it was tokenism. Did the Times review the exhibition?

BA It was reviewed. But what I am saying is that this was an example of not being able to deal with it. It would be like the magazine running an article on the Holocaust and putting Mr. Bloomingdale on the cover.

CG Can we talk about Provincetown. Is it a coincidence that I am doing a show with Benny Andrews, Emelio Cruz, Earl Pilgrim, and Bob Thompson, four Black artists who lived and worked in Provincetown?

BA Provincetown was different then from what it is now because the social circumstances have changed. Provincetown offered greater opportunities for Black artists not only to enter the arts but society for Black artists, for Black people actually. I first showed in Provincetown in 1960 at Paul Kessler Gallery. I had about twelve shows there from 1960 to 1972. Then I moved to Tirca Karlis’s gallery. What happened for people like me is that people who would be interested in you, artist-to-artist, would very often be in places like Provincetown. The town had a very diversified group of people because they were coming from someplace else. There’s so much freedom in that. I guess that’s why homosexuals do so much better there. Because you don’t have an established community there or established taboos. You have people who are from somewhere and they tend to be much more tolerant. It’s like Vegas conventions where people chase prostitutes, stay out all night, and do things they would never do at home. You have a freedom thing which includes race and everything else. Chaim Gross (1904–1991) was instrumental in helping me. He was always there, liked my work, though I didn’t know him. Bella Fishko, founder of Forum Gallery was there. Chaim recommended me, which is how I got into her gallery. Later I met Raphael Soyer who was with Forum Gallery. I remember a lot of people from that time; Bob Thompson, Nat Halper had a gallery, and Martha Jackson (gallerist) was around.

CG Do you recall Sun Gallery?

BA They were on the way out.

CG Did you know Bob Thompson (1937–1966)?

BA He came to Provincetown in ’58 or ’59, which is when I met him. I knew him very well. I was one of a few (figurative expressionist) like Bob, Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, Emilio Cruz, Jay Milder who were all there at that time. I came from New York in 1958. Jay and Red had a loft in the Lower East Side. Bob Thompson came in ’59 and met Red and Jay. Walter Chrysler (1875–1940) bought works.

Bob came in a big car, which I’ll never forget. I was living on Suffolk Street and he was looking for me because they had been telling him about me. Eventually we got to know each other. I was the only one married with children. The others were single. That summer Jay Milder, Bob Thompson, and Red Grooms went to Nebraska. All three planned to get married, but only Jay did. They all knew women there. Jay was from Omaha or Lincoln.

CG Is he still married to her?

BA No, but they had three children. Then Red returned and he and Jay set up the Delancey Street Museum, which was on the corner of Delancey and Suffolk. Mimi and Red moved in there. Red and Jay had been living together in a loft downtown. They would babysit for me. They would sleep and I would bring the kid in a carriage. They would get up at three in the afternoon when I returned. Then Bob moved in and Red was doing his happenings. He did Burning Building which premiered in Provincetown.

That’s when a lot of people were coming from the Village looking for drugs. There was a joke at the time that people were leaving New York to look for drugs in California and Californians were coming to New York for drugs. They would meet somewhere in the middle and say, “Go back.” People were abandoning their lofts, just putting on their hat and leaving. It was that On the Road Jack Kerouac time.

CG Earl Pilgrim and Lilly did just that—left suddenly for California.

BA You could just go around and pick up books and stuff off the street. I loaded up the baby carriage. That’s when Bob left for Louisville where he married Carol. They settled on Rivington Street in the Bowery. He was always painting. I would drop by with my kid but Bob was so into drugs that it would take and hour or two for him to wake up.

Eventually Bob would be up and we would shoot the breeze. Then some famous jazz musicians showed up and they would be doing drugs. They would kid me but I would just leave.

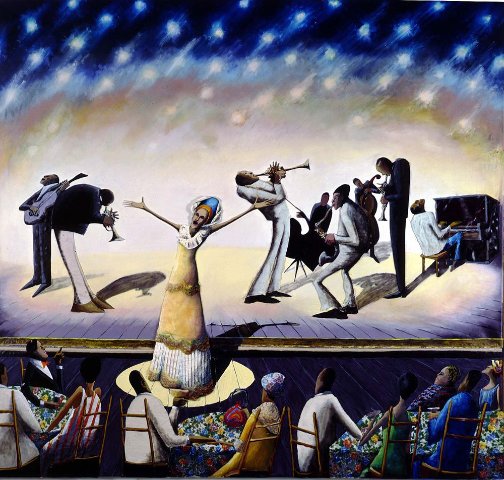

(Several are depicted in his large masterpiece Garden of Music in the collection of the Wadsworth Athenaeum.)

CG So he was part of the jazz scene.

BA There were recordings dedicated to him. Jackie McClean and those guys were dedicated to him.

CG It sounds like a scene from Jack Gelber’s play The Connection.

BA He played the drums. I have a poster of him performing as the drummer. They played in the Lower East Side and St. Mark’s Place. He existed in a world probably the freest world of race of any of us because he always had an entourage. We kidded that he was like Jack Johnson (1878–1946 World Champion boxer). He wore Italian silk suits with bowler hats. He would have shows and take people to Harlem. Not like Johnson in the 1920s but much nicer and more respectable the way Bob was doing it.

He joined Martha Jackson Gallery, but he got into drugs, which was unusual for an artist. In general artists smoke pot but don’t get into heavy drugs like he did.

CG That was the jazz world.

BA I used to do a lot of jazz sketching and would be out late at the Sagamore Café which was opposite to Cooper Union. I have drawings of Thelonius Monk and musicians at the Five Spot. At two or three in the morning people came in and the drug trafficking would start. Bob was into that but none of the rest of us. It got to be worse and worse like a bottomless bucket. He didn’t bother me about it because I had a wife and kid. There were artists who stopped being around him because he was always asking for money. He sold work but it was a bottomless bucket and he begged for money.

CG How did he keep working?

BA I don’t know but he just did. It took him longer and longer to get up during those days. It was afternoon when he dragged out of bed but he was always working.

CG How important was Bob Thompson?

BA It’s hard to explain how important he was because he did not have a vision that was restricted to what you say would be Black art.

CG With its Italian renaissance influences few would recognize the work as Black art.

BA Think of artists like Ensor who did subtle surrealist inspired paintings. He came from a very healthy family background in Louisville. He didn’t have a sense of oppression about being Black. Kentucky is a very difference state than where I came from in the deep South in Georgia. Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina, Georgia are real heavy southern states. Kentucky, North Carolina, Delaware, they’re light. People who come from those states didn’t grow up as oppressed as those in air-tight segregated societies. It shapes an individual differently. Bob was less scarred by racism than I was. That was reflected in his work.

CG The interest in Piero.

BA That’s what I’m saying. He didn’t feel as hard pressed to reflect on Black American concerns as a lot of us did. So, he was less identified with it. Not only that, but he was never involved, though he was a bit early on for it, in any Black-awareness social activities, in terms of any political activities.

In the eyes of Black people, he later suffered for that because they weren’t interested in him either. Jacob Lawrence and Charles White (1918–1979) especially were always given credit for being very self-conscious about race and doing all they could to identify with it. Bob didn’t do that one way or the other. In a sense, Sam Gilliam is similar to Bob. Today Sam is doing well and people are proud of him in a way. But, in his actions he doesn’t reflect what I do in my work. So, there is not much insistence on including him in Black anthologies. That’s changing now because the concept of it is different. It’s not required today in the way that it was in the ten-year stretch between 1965 and 1975 when it was a given that you had to pay your dues, without anyone consciously thinking it. There is no way to associate that Bob paid his.

CG He paid the ultimate price, he died.

BA I’m not talking about that. Martin Luther King also paid the ultimate price but he was a martyr.

CG Bob Thompson wasn’t a martyr but he was a victim.

BA There are some Black people whose art work is less respected. Dana Chandler’s work is less respected than Bob Thompson’s. But in the community (Boston) where people know him, they feel that he has made a greater contribution to Black people than Bob did. This is not to say that Bob should have acted differently. There are a lot of people who have no concern for things like that. In fact, there was a time when people were penalized because they painted abstractly. The point is that we are as diversified as anyone else.

CG The Boston artist Ellen Banks told me that she was chastised as a traitor to her race by another artist because she painted abstractly.

We have been talking about your work as well as other figurative expressionists who worked in Provincetown and New York: Lester Johnson, Jan Müller, Tony Vevers (not a New Yorker), Red Grooms, Jay Milder, Bob Thompson, Emilio Cruz. Clement Greenberg declared figurative painting to be reactionary. When the figure returned, it was identified as the new realism of Pop art. The figurative expressionist movement was weakened because major figures like Müller and Thompson died young. Johnson, a leading artist, was out of New York on a teaching gig. Isn’t it true that this major movement never received proper recognition?

BA When you discuss Greenberg and the world he operated in, you are not talking about any recognition of Black artists. There’s no reason for you to concern yourself with that. The artists you are talking about just did what they wanted to do. There were no critics with interest in them. They were not interested in what artists like us had to say.

CG When Thompson died in 1966 the Martha Jackson Gallery mounted a retrospective. They arranged for me to meet his widow Carol and view a number of works as well as those in the gallery. Rare for that time, I reviewed Thompson for the New York supplement of Boston’s Avatar. I was surprised when Judith Wilson found the review and included it in her Thompson bibliography.

Is lack of critical support still an issue for you?

BA For most of us it remains a problem, and I am a big problem for critics. For many reasons, one of which is that I write Black. That helps in a way because they can’t knock you down, but they won’t come near you. It works both ways.

It’s hard for critics to take criticism. That’s the first thing. They insist on being able to do the most despicable things to a practitioner, then take immediate offense to anyone who tried to objectively criticize them. John Canaday would write humiliating, belittling reviews. Anyone who tried to speak back was dismissed as a cry-baby. Not all, but the majority of critics behave this way. What we do and the way we behave, in the eyes of a lot of them who don’t know us from Adam, to them we are flaunting the law.

When you look at Thompson, Grooms, Johnson, people like us, they always have a problem. Are we primitive or what? If we are primitive, how the hell did we get through art school? That’s a problem they have. They can’t figure out that maybe you can do something else. In my case they can’t reconcile that I can also be an administrator, or that I’m a strong advocate for the rights of Black people. I am also in a strong position to do something for everyone’s rights. When I was at the Endowment there were times when I argued against giving preferential treatment to any one group. I was going against what was best and I felt you shouldn’t do things like that.

CG Do you believe in a quota system?

BA Yes, I do believe in a quota system. But there are ways to best do that. I try not to accept generalities.

I feel there should be a quota system for school bussing. I believe in bussing. We must try to make up for, compensate and assist any group that has been deprived. When I grew up no matter how far we were from schools there were no busses for Black students. No matter how close to schools White kids lived, however, there were busses. That took them a long way past our schools which they could have walked to. I’m just giving you an example of racial inequality. If you are going to wait for the system to include Black people, it’s never going to happen.