Venice: Peggy Guggenheim Museum, Palazzo Cini, Santa Maria della Salute

The Absinthe Minded Professor

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 06, 2008

On another rainy day in Venice, last fall, we visited museums and Santa Maria della Salute, all within a short walk from our lodging, at the Don Orione complex in the Dorsodsuro section, near the Accademia vaparetto stop. From the Grand Canal one views the Peggy Guggenheim Museum a short distance from Santa Maria della Salute which marks the tip of the peninsula.

I last visited the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in 1975 and swear that it was Peggy herself seated at the dining room table. At the time there were limited hours for visiting the collection which was still a private home for Guggenheim (1898-1979). During her life she explored several possibilities for establishing a museum. Particularly after she closed the seminal New York Gallery, Art of This Century, and returned to Europe at the end of World War Two.

While living in Paris, particularly in the final days before the Nazi occupation, she frantically visited studios and purchased works at drastic discounts. Not only was she acquiring and saving works of art there was also the matter of her own safety and that of her entourage. After many harrowing experiences she managed to charter a plane and flew from Portugal to New York with Max Ernst, several other individuals, and the collection she had rescued.

During the war, she and the gallery became a focal point for the Surrealists in exile including the leader of the movement, Andre Breton. Her friend, Marcel Duchamp, helped to organize exhibitions including one of collages which was how she came in contact with young American artists including Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock. For a time, she supported Pollock on a retainer and owned all of the work he produced during that arrangement. Many of these paintings she subsequently donated to museums and there are major examples of his paintings on view in Venice.

From her husband Laurence Vail, a surrealist artist, she had two children, Pegeen and Sinbad. She divorced him when he had an affair with and later married the author, Kay Boyle. A room in the Venice museum, originally the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, is dedicated to the primitive, figurative paintings of the troubled Pegeen who took her life in 1967. Peggy is quoted as having told Pegeen that she would rather own a Picasso than have a daughter.

The Peggy Guggenheim Museum, which is now managed by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, is one of the most remarkable in the field of modern art. While relatively small it is densely packed with the works of her artist friends and lovers both in Europe and New York. Until rather recently it was the only venue for modern art in Venice other than the displays of the Biennale. In fact her collection was first publicly displayed in the Greek pavilion of a Biennale. This led to the interest of opening her home to the public on a limited basis during her lifetime.

It is alleged, and reported to me by one who was present at the time, that there were negotiations with a representative of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston to acquire the collection. But the meeting ended abruptly. The decision to have the collection managed by the foundation of her uncle (her father, Benjamin Guggenheim, went down with the Titanic in 1912) occurred as an alternative to establishing an independent museum.

It was with great anticipation that we planned a visit to the museum. Along the way we passed the friendly, local absinthe shop. Being an absinthe minded professor, I could not pass up the opportunity. The Czech brewed bottle that I purchased came with its own traditional spoon. This is placed on top of the glass with a sugar cube and the bitter, medicinal absinthe is poured over it. Passing through customs I declared it as an aperitif.

Along the way we passed the Palazzo Cini. In addition to a small but choice permanent collection, including a rare Madonna and Child by Piero della Francesca, there was a special exhibition by the Venetian portrait artist, Rosalba Carriera (1702-1785). She enjoyed great success in Paris in 1721 when she created portraits of the Royal Family as well as the artist Watteau. She was elected to the Academy and enjoyed an active professional life. While she has been elevated to a position of importance by feminist art historians, for me, the work was not of great interest. But this was an opportunity to see her portraits in depth. Carriera was particularly skilled in creating miniatures and in the medium of pastel.

In addition to viewing the works in the Guggenheim Collection, with its great strength in Surrealism, particularly remarkable works by Kazimir Malevich, Max Ernst and Magritte, there were other special exhibitions. Since 1997, the museum has displayed twenty six works from the collection of Gianni Mattioli with remarkable examples of paintings by the Italian Futurists: Balla, Boccioni, Carra, Depero, Russolo and Severini. As well as paintings by Modigliani, and Morandi. Within its limits the selection represents a superb insight to the accomplishments of early Italian modernism.

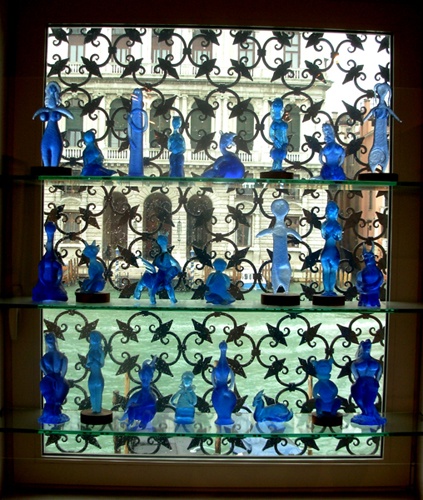

In another part of the museum there was a special exhibition of the sculpture of the Italian modernist sculptor, Medardo Rosso (1858-1928). There was a selection of his figurative pieces which were generally small in scale and comprised mostly heads and busts as well as a few group pieces. The works on view included plasters and bronzes as well as some figures in wax as well as wax applied over plaster. There were also examples by this artist that we encountered at the Museo Fortuny. The work of Rosso has long had a cult status as a neglected minor master of the period who is viewed as a particularly poetic artist.

In addition to exploring the galleries of the museum we also stepped out onto the terrace with its vistas of the Grand Canal. There was a small Calder sculpture at one end and horses at the other. The American artist, Alexander Calder, was a great friend of the collector and designed her bed as well as jewelry.

On the broad steps descending to the terrace is one of the most notorious works in the collection. The horse and rider sculpture by Marino Marini has an interesting feature, an erect penis, which one may unscrew. She had the option to remove the member on such occasions when the Pope, perhaps, wafted by in a ceremonial gondola.

It was an object in which Peggy, in her scandalous auto biography, expressed considerable and diverse interest. In the first edition of the book she concealed the identity of her many lovers. But everyone easily guessed who they were. So, for the second edition, she famously named names. It was almost an insult to the manhood of many famous artist and writer friends not to make the list. It was a sport in which she and Pegeen were often noted as competitors.

On the day of our visit, mid-week in the 'off season,' the museum was packed. This included the cafeteria where we planned an intimate lunch. It proved to be a mistake as I grew impatient with waiting. So we left and ended up having two outrageously expensive bowls of soup. Hey, that's Venice, where the Euro certainly does not give you much bang for the buck. A woman working in the restaurant seemed not quite right in the testa and appeared to be laughing at us. These are the odd adventures of travel particularly on cloudy days.

After our elegant little lunch we darted back through the rain toward Santa Maria della Salute which is a short distance beyond the Guggenheim Musuem. The Venetian Senate decreed the building of the new church in 1630 following a wave of the plague in 1629. The title of the church is translated as Basilica of Saint Mary of Health/ Salvation. After San Marco it is the next most famous and remarkable church in Venice. The competition to design the church was won by the architect Baldassare Longhena (1598-1682). Construction was completed in 1681 the year before the death of the architect. It was built on a platform resting on 100,000 wooden piles. The octagonal shape reveals a magnificent domed interior. Unfortunately, during our visit the dome was being repaired which obscured its exterior with scaffolding.

Having viewed the interior of the church I planned to step out on the terrace to photograph panoramas of the magnificent views. But it started to rain cats and dogs. When there appeared to be a bit of a letup we sprinted to the nearby vaparetto stop. So I never got those shots. Oh well. So much for a rainy day in Venice.