Touring Carnivals Europe and Americas

Part One: Trinidad, Quebec, Venice, and Basel

By: Zeren Earls - Jan 07, 2013

Dating back to the Middle Ages, Carnival, meaning “farewell to flesh” in Latin, is a celebration that marks the beginning of Lent. While the aim of all carnivals is the pleasure of playing, each one is unique based on the tradition, culture, and climate of the country where it is observed. During the years when I directed First Night Boston and First Night International, I attended nine carnivals — Trinidad, Quebec, Venice, Basel, Nice, Tenerife, Binche, Aalst, and Viareggio — to observe the community’s involvement and to glean ideas applicable to our own celebrations.

My first adventure was in 1982 and began with a charter flight to Port of Spain, Trinidad. Accompanied by my late husband Paul, who came prepared with his tape recorder, we were surrounded by a profusion of color and rhythm upon arrival. Steel bands rehearsed in empty lots, while mas (“masquerades”) unfolded on hillsides.

At dawn on Jour Ouvert (opening day), the two-day reign of the Carnival King began with steel band music by players, descending from the hills. As musicians and revelers moved toward the carnival grounds, across from magnificent mansions, they smeared black chalk on all white faces watching and pulled us into their ranks.

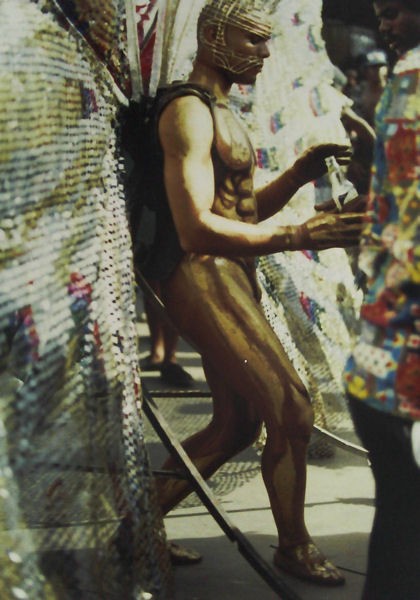

On the staging ground, known as the “Savannah,” were a large band of 2300 papillons — human butterflies spread out in a dramatic explosion of primary colors, their wing spans varying from 8 to 25 feet. Also engaged in kinetic fury, other masqueraders formed smaller bands with different costumes in varying sizes and clashing colors, such as the Queen of Dracula, the Scorpion Fish, and the Phoenix. The bands moved along a track leading to a ramp, which took them up to the confines of the competition area. Masqueraders shuffled to the music in their procession, creating a spectacle for the crowds in the stands. Upon receiving the People’s Choice Award, the butterflies crossed the stage and shed their wings, taking on majestic gilded human forms.

Another day was dedicated to the Junior Carnival Parade, which took place on the streets of Port of Spain. Following weeks of hard work and organization on the part of teachers and students, including many with physical, hearing or visual disabilities, all basked in the admiration of the crowds as they passed by.

Children grow up with carnival in their blood. Every young boy’s dream is to play in a band. Many children become full-time musicians, annually competing in preliminary, semifinal and regional championships. Qualifying to perform on the big stage is a mark of distinction. We were treated to a musical feast of 19 bands playing indigenous music on Music Awards Night, which included the Calypso King Championship, held to select the year’s top ten albums.

The Carnival Champions Awards took place on an indoor stage on the night of Dimanche Gras. Finalists competed for first, second, and third place. The Male and Female Individuals of the Year were chosen among the contestants. The sweet but fleeting nature of “Life” was symbolized by the face of Marilyn Monroe sequined into a large butterfly wing. Among the winged heroes were Che Guevara and Muhammad Ali.

Carnival was brought to Trinidad by French settlers, who colonized the island. In addition to the European background, the African and East Indian heritage of the locals helps shape the splendor and drama of the celebration. Band leaders, designers, steel drummers, and calypso musicians spend weeks in neighborhoods organizing for the event. Participants learn the skills of wire and cane bending, as well as working with materials such as satin, chiffon, velvet, feathers, foil and glitter. The entire community works together to create splendor and to play, with a dose of mockery and taunting.

Sharing my papillon images with Boston artists inspired them to create unique butterflies for the First Night procession. Also encouraged by my experience, I was able to convince the city’s Caribbean community to reveal itself downtown, despite the cold weather on New Year’s Eve.

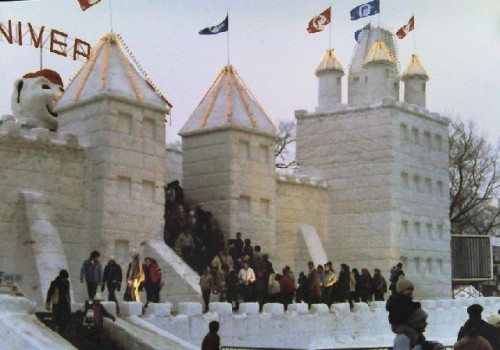

In 1984 my carnival adventure took me to Quebec, Canada, where the festivities were shaped by the region’s climate. The carnival was a celebration of snow; its players were the people. A magnificent snow castle built over a wooden armature dominated the city center. Street entrances welcomed celebrants with a joyous snowman. Sidewalks displayed snow sculptures, ranging from a gigantic tube of toothpaste to people watching a human-size TV, while restaurants featured their own displays by their entrance. None of the sculptures were barricaded from the public; carefree children climbed on and around them with abandon.

In the evening a parade of big floats, their shapes delineated in lights, greeted bundled-up onlookers for hours. Horse and carriage rides enhanced the festivities as they shuttled people to and from the illuminated castle.

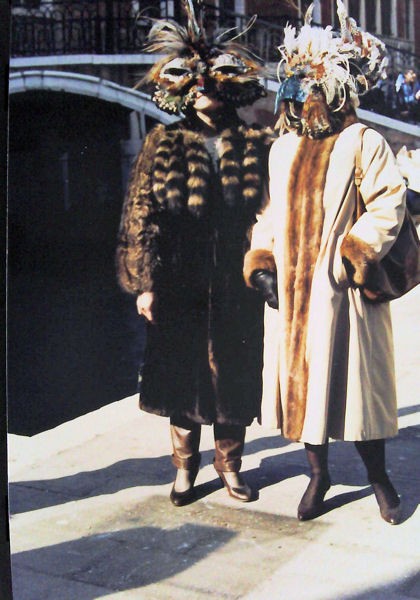

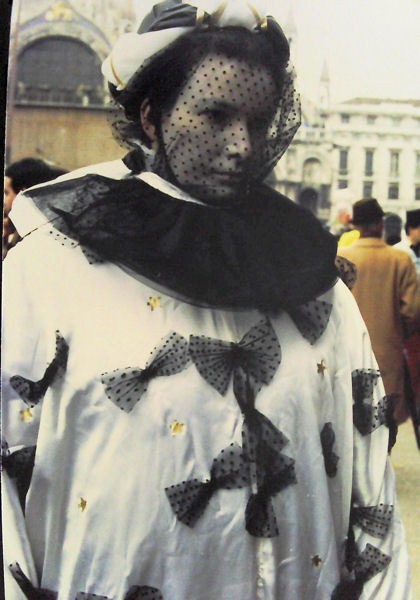

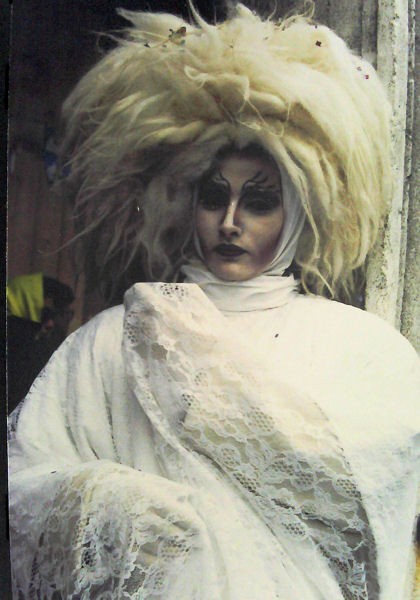

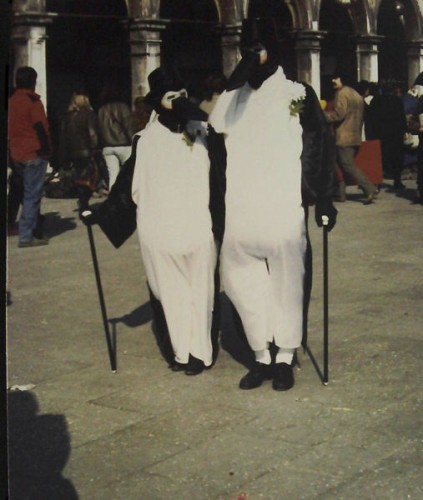

In 1985 my destination was Venice, Italy for the Carnevale, a masked ball lasting ten surreal days. With the Piazza San Marco as the centerpiece for many of the festivities, participants caroused and carried on their daily lives in masterful disguise. Concocting fantasies in satin and tulle and in haunting expressionless masks, the people were the players in a stage set of palazzi (palatial mansions) along the canals and spanning bridges. Masked figures stood in doorways, looked out windows or sat around fountains, posing for passers-by. As an influx of revelers arrived at the train station, they too quickly donned costumes, stretching the limits of the imagination and enhancing the flashes of color that electrified the city’s grey February air.

Born from the Roman Saturnalian feasts, Venetian carnival is an elaborate pre-Lent celebration, with dozens of masked balls, in addition to street dancing and parades of people and gondolas. People attend the balls in 17th-century finery, much of which has traditional significance dating back to medieval times. After falling dormant with the surrender of the Venetian city-states to Napoleon in 1797, Carnevale was revived in 1980. One indelible image I came away with was of a woman dressed in gold from head to toe, standing still in a doorway. Encouraging Boston’s First Night celebrants to turn out in costume thus became a goal of mine.

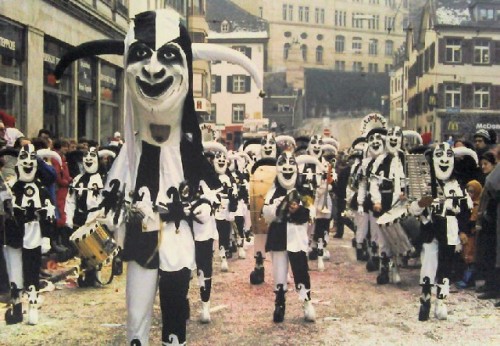

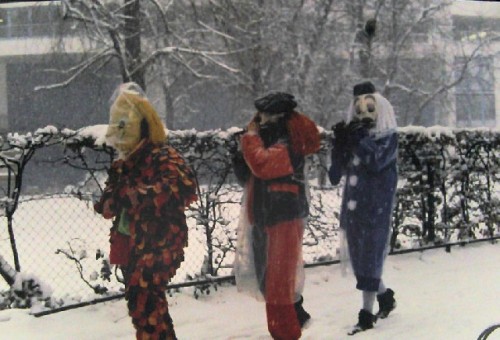

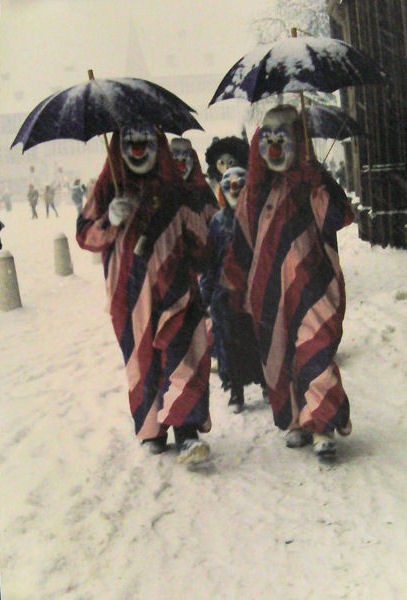

In 1986 my trip to Basel, Switzerland was another enchanting experience. Known as Fasnacht, the three-day carnival opens at 4 am with the Morgeschtraich, or “morning stroke.” The entire city was shrouded in darkness as music — a slow rhythmic tune played in unison on high-pitched pipe and drum — arose from the streets and alleyways in central Basel. The players emerged, lit by lanterns borne on their heads and with their faces hidden behind masks, and led the crowds to various hotels for the traditional flour soup, ladled out of big kettles for free by the staff. Warmed up by the soup, crowds and carnival participants returned to the streets for merriment.

Carnival generally means a suspension of ordinary routine and a reversal of roles — the lowly are exalted, the jester becomes king or priest, men act as women and women as men, and humans turn into beasts. The disguises help to relax rules, resulting in varying degrees of licentiousness and the freedom to criticize neighbors or town officials, often through satire.The aggression is playful and indiscriminate; the weapon in Basel is confetti.

Basel is one of the few Protestant cities anywhere to hold a traditional carnival. To separate Fasnacht from religious associations, the festival in Basel is begun a week later than most carnivals and after Catholics have already begun Lent. The theater of the carnival, with its intricate costumes, masks, and lanterns, as well as the music, wit and orderly structure, allow locals to celebrate in a unique and playful way. There is a clear separation between participants and observers; participants are the only ones permitted to wear masks and costumes.

People participate actively in Basel’s Fasnacht by joining various organizations. Those that make up the large parades are the Cliquen, groups of 25-200 people in costume and mask playing piccolos and drums. The large Cliquen are divided into groups with an average of 40 people in each. The festivities open with the Morgeschtraich, which provides the musical undertone for the festival. Many of the traditional tunes are fife-and-drum marches. On the afternoon of the first and last day of carnival, all the Cliquen march together in a parade, their themes painted on huge rectangular lanterns and expressed in their costumes. In the evenings the lit lanterns are exhibited in a hall for public view.

A second large body of participants are the members of Guggemuusig groups. They also wear a variation on a chosen costume and play an instrument, but the music itself is a parody. Literally meaning “music from paper bags,” Guggemuusig involves musicians playing distortions of traditional marches out of tune on instruments ranging from drums and horns to noisemakers.

A third way of participating is to bring in a Waggiswaage, a large hay wagon loaded with flowers, oranges, confetti, and candy with which to pelt the crowds. The Waggis who ride the wagon wear wooden clogs and masks topped with wild, bushy hair, often bright green or orange.

Unexpectedly coming upon groups of two to six masked people in costume, moving through streets softened by pastel-colored confetti with their music permeating the air, inspired me to introduce Street Surprises to Boston’s First Night. During the days leading up to the event, people encountered costumed characters during their lunch hour or on the way home from work.

(To be continued)