Ada Louse Huxtable Dead At 91

Eloquent Critic of Architecture and Built Environment

By: Mark Favermann - Jan 08, 2013

On the occasion of the passing of the renowned architectural critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, we are reposting our prior coverage in 2008. Editor

On Architecture: Collected Reflections On A Century of Change

By Ada Louise Huxtable

Published by Walker & Company, New York, New York

October 2008. 464 Pages

Ada Louise Huxtable defines the term architectural critic. She expresses the essence of what architecture is. By her fluent wording and eloquent phrasing, a clear sense of place, physical space and exact time are portrayed with understandable images and straightforward references.

In fact, her style is so expressive and accessible that she defines the notion of critic of any kind. In 1970, while writing for The New York Times, Mrs. Huxtable won the first Pulitzer Prize for "distinguished criticism."

Her latest book, On Architecture: Collected Reflections on a Century of Change (Oct. 2008), is a series of her various and usually astutely wonderful pieces from five decades of observing and critiquing architecture and the urban environment. She has virtually shaped the conversation on architecture in the United States and acted as the conscience of the nation's architectural community for nearly half a century.

With this in mind, it is a rare treat to read for the first time, as well as once again, several of her articles and essays dealing with the prominent issues of the built environment in the latter half of the 20th Century and the first decade of this century. The observations are keen, the cultural context clear and her sensibilities are at once sophisticated yet always down to earth.

Ada Louise Huxtable makes criticism seem easy and accessible to read. Architectural history is made to be a handmaiden to practical knowledge. Style and function are described as servants to contemporary design and building construction. The inner workings of city politics as they affected the development business have been fairly chronicled by her as well.

Born in New York City, she received an AB from Hunter College in 1941 and married industrial designer L. Garth Huxtable in 1942. She did graduate studies at New York University. She served as Curatorial Assistant for architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art from 1946-50. She was the contributing editor at Progressive Architecture and Art in America from 1950-63.

Mrs. Huxtable was named the first architecture critic at The New York Times in 1963 and served in that capacity until 1982. She wrote for The New York Review of Books and is currently the architecture critic for The Wall Street Journal. Throughout her career, when she spoke or wrote, architects, developers, politicians and bureaucrats listened and often had to duck or be chastised.

On Architecture is divided into several sections. The first "The Way We Were" looks back at the decades covered in the selected essays in the book to suggest the nature of the times. The Way We Built showcases a selection of iconic structures of the 20th Century when Modernism was at its corporate and institutional zenith even as rumblings were occurring counter to its total establishment embrace.

The section "Modernism and Its Discontents" speaks to the open rebellion and aesthetic reaction to Modernism. The last two sections "Reinventing Architecture" and "Rewriting History" deal with new work and ideas.

These later sections deal with architects whose designs did not play by the rules of Modernism. These rebellious individuals and their brave clients enormously influenced architecture as a profession and design as a whole.

Others are discussed who had an approach and style of design that were not recognized by modernism because they were not mainstream, purists. These works were considered too revolutionary by the architectural and critical establishment. As controversial as much of this design was, now all of it has been absorbed into the mainstream.

Interestingly, in her introduction, Huxtable speaks to the "courage and genius' of the great earlier works that endure. She compares the "attitude, novelty and fashionable edginess" of today's architectural practitioners to the recent past. To her, this is a time of chic, hard-edged minimalism.

She counters that Alvar Aalto's more soft-edged humanism invites an experience that combines people and nature in his buildings. Louis Kahn seems to elevate the human condition in his structures underscoring a sense of dignity and individual worth. And Mies van der Rohe's works demonstrate the precise and near perfect elimination needed to reach for simple beauty. Here less can be absolutely more.

Ada Luise Huxtable is fascinated by the way reputations have gone up and down over the years. She says that each generation sees what it wants to see and writes its own contextural script. She sees Yale's Art and Architecture Building as an example of the generational love/hate process. This 1971 structure by Paul Rudolph was championed by her when it was built for its heroic brutalist forms and complex interlocking levels, but several generations of faculty and students hated it for its multilayered interiors and uncomfortable work and teaching spaces.

Eventually, it was configured by students with self-constructed minispaces for their work areas and a mysterious and damaging fire occurred. Thirty years later the building has been restored and celebrated by a new generation as "a masterpiece of space, light and mass."

Considering it a concrete bunker along the Hudson River, she vilified New York City's Jacob Javits Convention Center. Huxtable advocated that it should be redesigned in glass. This she now refers to a "lump of coal' and considers it a prime architectural example of The Law of Unexpected Consequences.

She is a bit flabbergasted that "the General Motors Building that brought mediocrity and a dismal, redundant plaza to the most elegant part of New York's Fifth Avenue would be redeemed by the Apple Store's magic crystal cube on a newly elevated plaza, turning disaster into triumph." Reading Ada Louise Huxtable is enlightening and fun.

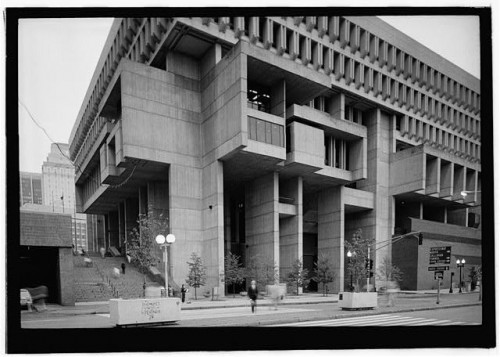

Two structures, very current in architectural dialogue, were written about by Huxtable at the time of their completion. They are as controversial today as they were back then. The first is Boston's New City Hall (1967) and the now The Museum of Arts and Design, the once "Lollipop Building" in New York. Link to review. Uncompromisingly dramatic with rough concrete forms, Boston's City Hall has gone from one of the most celebrated buildings in the world, once ranked 5th best on some best world architecture lists, to the most hated structure in Boston.

Boston's longtime Mayor Menino wants to sell it or tear it down. It was designed by Kallmann, McKinnell and Knowles in a 1962 world architectural design competition at the height of the Brutalist style. Initially Huxtable felt it had "a dignity and an openness that belied Boston's notoriously convoluted politics."

She now feels that the building was particularly abused and not well served by the politicians and bureaucracy that inhabited it. Huxtable admired the building when it was first built and against convention still admires it today.

The "Lollipop Building," so referred to by others after Mrs. Huxtable wrote that part of its ornamentation was like lollipops, is the former Huntington Hartford's Gallery of Modern Art Building (1964) at 2 Columbus Circle in New York City. The building by architect Edward Durell Stone was a reaction to Modernism. Ada Louise Huxtable unfavorably reviewed it and called the structure a "die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollipops."

It was a stylistic reaction by Stone to the International Style or minimalist modernism. Of course, Minimalists felt that the façade was too over the top. Three decades later, Huxtable along with others who had maligned it, began to see it as a distinctive period piece. Now it is gone and replaced by the Arts and Design Museum's new façade. Huxtable is now wistful about the older building.

Ada Louise Huxtable's writing gives great pleasure. Her words smoothly challenge us to look, actually to see, to think, to react and to ultimately be inspired. She is a great gift to our built environment and how we perceive it. On Architecture is a wonderful compilation of ideas, form about function and contemporary cultural history.