Kerry James Marshall: Mastry

At Met Breuer

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 08, 2017

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry

Met Breuer

To January 29, 2017

Now 61, the retrospective Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, installed on two floors of New York’s Met Breuer, confirms that he is the first among several, top-tier African American artists.

Deeply rooted in the American tradition of genre, history painting and social realism the work, while riveting and evocative, may be regarded as conservative when compared to the cutting edge of contemporary art.

By any means necessary, however, he has created large, complex, dense works that with clarity, precision and insight affirm that black lives matter.

Here and there teeth flash in his biting attack on racism in America. More significantly, however, he has made the routine life of black people front and center in epic works celebrated on the walls of major museums.

It is likely that the work will be seen differently by white and black audiences. It represents for most, an intensive immersion in an unfamiliar world, but for people of color it offers gripping signifiers.

There is a connection between these vignettes from Marshall and the Century Cycle of ten plays by August Wilson. While Marshall conveys daily life in housing projects, homes, and beauty parlors in LA and Chicago, Wilson focused his plays on a black neighborhood in his native Pittsburgh.

In a 60 Minutes interview, Denzel Washington, who directed and stars in Wilson’s Fences explained “It’s not about race. It’s about culture.” That subtle but important difference is not readily apparent to museum visitors or theatre and cinema audiences.

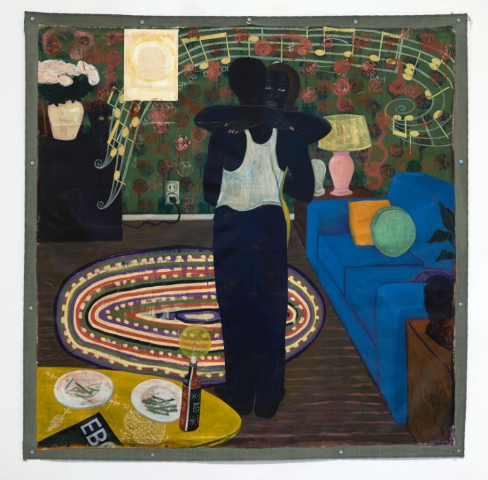

Deeply rooted in language, music and art, initially for self protection, there is a codified, hip, ironic and often hilarious manner in which black people talk to and about each other.

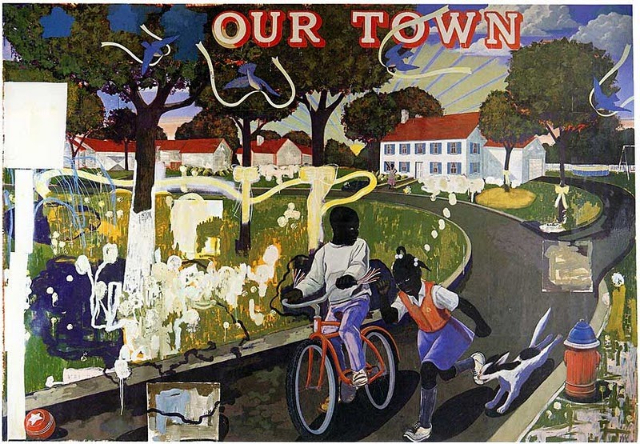

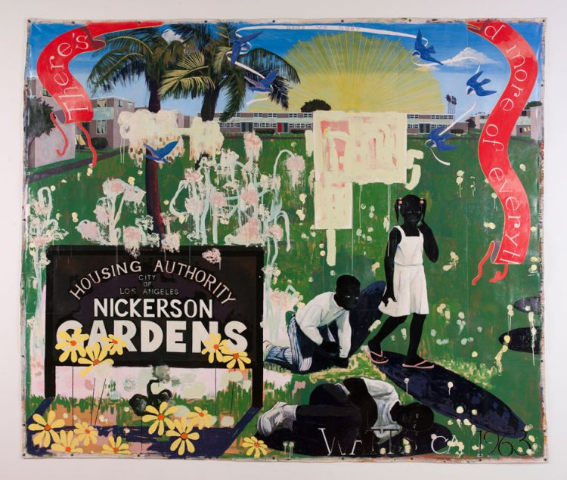

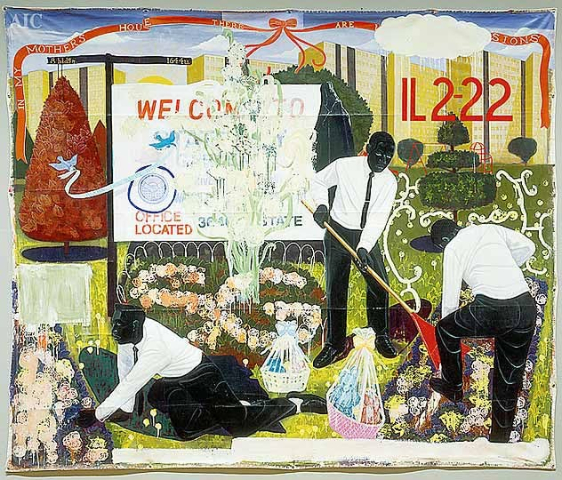

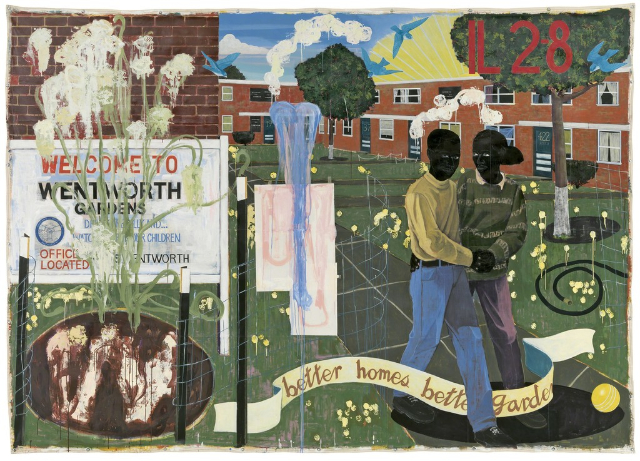

Occasionally, the attack and anger is sharp and specific but more often it is not. This overview of Marshall’s work allows us to flow through and absorb the running narrative of series like “The Garden Project.” We see folks and kids, at work and play, going about their business. They ride bikes, play games, swim, water ski and sail.

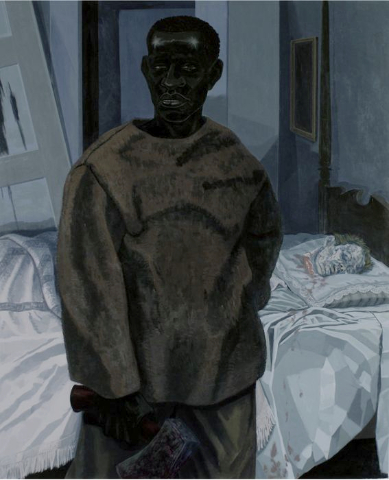

Then there are maximum impact, gotcha paintings like “Portrait of Nat Turner With the Head of his Master.” It is included in a room of portraits of heroes, martyrs, terrorists and assassins. There is Harriet Tubman with her husband.

Surprisingly, what to make of Julian Carlton, an estate worker originally from Barbados? Employed by Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesen (Wisconsin), shortly after being fired, he went a rampage murdering Wright’s mistress, Mamah Borthwick, her two children, and several other people. He torched the building before attempting to take his life with acid. Carlton died several days later while in custody. Marshall’s brooding portrait is of an actor who portrayed Carlton.

We are kept off balance as the pendulum swings in Marshall’s work. It can be as evocative and heart warming as a delta blues song or as scorching as a Molotov cocktail.

There is a series of portraits of young black men wearing hoodies. They reference the young, gifted, and black gunned down by cops. You look at the images and speculate what might have been for lives that matter.

In ironic self reflection Marshall created a series of imagined black artists. We see these men and women wielding enormous easels. With a twist it recalled self portraits by Vermeer, Rembrandt and Judith Leyster in their studios.

Particularly in “The Garden Project” the compositions are dense and busy. There is a lot going on including signage and floating banners with text. We wondered about occasional splotches of paint. The Times critic speculated that they may represent bullet holes.

In some of the most evocative works he takes us into homes and beauty parlors.

In “De Style” (perhaps a riff on the Dutch movement di Stijl) we view several customers having their hair done in an outrageous manner. A client seated in the chair is being given a more conventional cut.

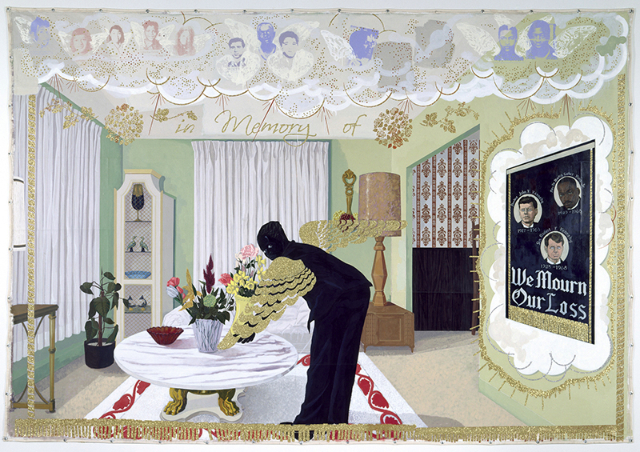

The painting “Souvenir 1” of a well decorated, neat, middle-class living room depicts a woman, with outstretched, gold, angel wings bent over a coffee table. On the wall is a framed picture of J.F.K., Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King with the text “We mourn our Loss.” In a proscenium-like design above her is a banner proclaiming “In Memory Of.” Over that is a panorama of portraits and labels for black leaders and martyrs.

The retrospective includes early works as well as experiments. They represent a range of diversions and paths not followed. Another part of the project includes works that Marshall was allowed to borrow from the Met’s permanent collection. There are old masters as well as earlier African American artists including the outsider artist, Horace Pippin, and the imposing print of John Brown by Charles White.

Surveying the work one absorbs that Marshall has an astute and pragmatic grasp of art history.

This can generate interesting, ironic and amusing connections. There is a painting of several people sailing on a sloop. The composition and arrangement of figures evoked American masterpieces like “Breezing Up” by Winslow Homer or the MFA’s “Starting Out After Rail” by Thomas Eakins. That reference is so esoteric that it was an inside joke that had me doubled over.

We initiated this review by suggesting that Marshall is both socially and politically current while arguably conservative and reactionary stylistically. This is remarkably like how I felt when recently attending a production of an August Wilson play “The Piano Lesson” in Hartford.

Perhaps that reflects an understanding of their primary audience. As the congregation exclaims to its pastor “Make it plain.”

Marshall’s figures are clear and didactic. There is a poster-like flattening with little or no chiaroscuro. He does not seduce the eye with slick trompe l’oeil. Nothing messes up or complicates the message. One finds in Marshall’s work echoes of paintings by Jacob Lawrence, Phillip Evergood or Ben Shahn that also told it like it is.

A version of this article was published in Boston's The Arts Fuse.