Yale University Art Gallery Reopens

America's Oldest University Art Museum

By: Richard Friswell - Jan 12, 2013

A recent tour of the newly expanded and renovated Yale University Art Gallery, in New Haven Connecticut, has visitors treading on a little-noticed engraved marker inlayed in the stone floor of the Ancient Arts gallery. Cool winter light slants into the space from nearby Chapel Street, illuminating the inscription: ‘Col. JOHN TRUMBULL, Patriot and Artist, Friend and Aid (sic) of WASHINGTON, lies beside his wife beneath this GALLERY OF ART. Lebanon 1756 – New York 1843.’

Look on the back side of any hard-to-find two-dollar bill and you can find a representation of Trumbull’s famous 1817 masterpiece, The Declaration of Independence. Large-scale versions of several pieces from his Revolutionary War series found their way into Bullfinch-designed niches in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C. a decade later, but the smaller studies were eventually donated by a dispirited Trumbull to Yale University, after discovering, late in his life, that the American public had little appetite for history paintings, especially for events and personalities so recently transpired.

With his donation to the school, and the promise that he would be interred nearby (“these paintings are my children…let me be buried with my family. I have long lived among the dead.”), Yale was on its way to becoming the America’s first university museum.

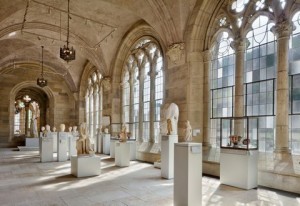

A suitable building, Street Hall (1866) was soon erected to house the Trumbull works and other ephemera that began to stream in from private collections and archeological digs around the world. This Ruskinian Gothic structure has served many functions over the last hundred years, including student studio classrooms, administrative offices and pigeon roosts in the empty tower overlooking the Yale campus.

Now, after a 16-year, $135 million planning, assessment and restoration project under the direction of New York-based architectural firm, Ennnead, lead by design partner, Richard Olcott and management partner, Duncan Hazard, the three buildings, spanning over one-hundred years of design sensibility have been united into a 70,000 square foot complex.

Anchoring the gallery at one end is the sleek concrete and glass Kahn Gallery (1953), a landmark space envisioned by Yale’s one-time dean of the School of Architecture. Its north-facing, street-level window complex tempts the passer-by with glimpses of the treasures contained there-in. The Kahn Gallery, already suffering by the mid-90s from the effects of experimental design concepts so prevalent in the early-modern design movement, required the attention of the architects and construction specialists as a first priority.

Next in line was the neighboring and contiguous Old Yale Art Gallery (1928), an Italianate Gothic structure whose glowing, wedding cake masonry façade and leaded glass windows lay buried under decades of city soot and acid rain discoloration.

As the scaffolding came down around this multi-year renovation project, the result is a museum space that effectively integrates architecture and art into a seamless and well-conceived tour of 5000-years of art, ethno-culture and functional design.

The art gallery staff has augmented the objects and painting previously on display with an additional 20,000 items, including many masterpieces from their quarter-of-a-million object collection, much of which had never been on display before. “We had six Rothkos in storage and had to decide which three we wanted to have on display,” said Jock Reynolds, museum director, as he toured us through the newly-added, high-ceiling Modern and Contemporary Art gallery.

For Yale, this new space in not so much an embarrassment of riches as it is an opportunity to bring vast portions of their accumulated works into the public arena. “We are now the eighth-largest museum in the U.S., and we remain committed to our mission to be a free resource for the community—from school children to our students here at Yale and other academic institutions, to anyone interested in travelling to New Haven to interact with our collections. Our goal with this transition is to collectively transform the three-building complex into a laboratory in which to learn and think about art,” Reynolds tells me.

A thorough, but rapidly-paced tour of the new facilities was necessary, because there is too much to absorb in just a few hours. What was once a local university gallery offering a rainy afternoon’s diversion is now a comprehensive cultural experience requiring several days to truly appreciate all it has to offer.

Some of the highlights include.

The Yale collection has received a boost over the years from wealthy alumni and benefactors. The result is depth and quality in many of the collections on display.

The second floor of the Kahn building is given over to an extraordinary gathering of artifacts from the Indo-Pacific region. Aided by a gift from Thomas Jaffe, his collection of ethnographic sculpture, Javanese gold from the prehistoric to the late medieval period and Indonesian textiles are now skillfully displayed and curated by Ruth Barnes, formerly with University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum of Art. Richly informative text panels lead the visitor through an explanation of the unifying themes of that region’s cultures, including ancestor worship, the world of spirits, concepts of fertility, warfare and headhunting.

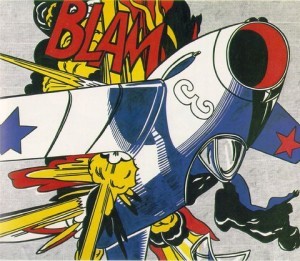

The famed Louis Kahn honeycombed, poured-concrete ceiling also hangs low over a portion of the Modern and Contemporary Art collection. Again, gifting by several generous alumni make this gallery experience a compelling walk through the visual arts of the 20th century. A period of deep reflection on the part of international artists reassessing the relationship between such long-held assumptions as perception and representation, objects and their freighted cultural meaning, form and perspective are all represented in Yale holdings now on display. The brilliant primary colors of Josef Albers geometric constructs appear to glow on concrete cinder block walls; Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic, Blam (1962) blasts its way into the room with hyperbolic intensity; Picasso’s Cubist portraits’ vibrancy of color and composition are still arresting nearly a century after their creation; Jackson Pollock’s’ Number 13A: Arabesque (1948) speaks to the physicality of Abstract Expressionism, as the viewer imagines the painter dancing over his canvas with paint brush dripping, as the title implies.

The European Art Gallery encompasses nearly 2,000 objects, spanning the ninth through the nineteenth century. Particular strong in Italian art of the early Renaissance, the deep mulberry-painted walls add a tone of intimacy and regal standing to the many works depicting religious figures and biblical scenes. These gold-field painting are frequently bypassed by museum goers as staid and iconoclastic in their motifs. Yale’s collection, acquired as a collection by James Jackson Jarvis in 1871, deserves a second look, as the number of works on display in this has tripled to include masterpieces by de Fabriano, Pallaiuolo, Bosch, and later works by Holbein, Hals and Rubins. Not to be missed is the modestly-sized Rubens portrait, Head of a Bearded Man in Profile, a study used as a model in other works, but radiating life through layers of flesh-toned oil paint, still vibrant after centuries.

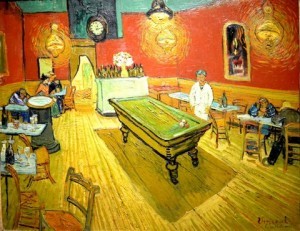

Spanning the centuries, this expanded gallery also houses a wide range of Impressionist masterpieces, including Manet, Monet and the iconic Post-Impressionist work by van Gogh, The Night Café (1888), whose vibrancy and impasto brush strokes suggest a third dimension to the work.

The new Wang Galleries of American and Decorative Arts chronicles American functional design from the colonial period to 1900. The architectural detailing of the original Street Hall building lends itself best to displaying these rarely-viewed artifacts of our cultural heritage. Chestnut wainscoting and pine molding grained to match (by trompe l’œil specialist Marc Petocsky of MJP Studios), other large-scale architectural elements from the collection, many of which have not been displayed before, enhance the visitor’s experience, including the front door and reconstructed room from the Rose House, of North Branford, CT (see below, left) and a carefully-reassembled parlor (including original paint) from the Rowley House (ca. 1770) of Gilead, CT.

The Yale silver collection is one of the most extensive of any academic museum, spanning three centuries. Elaborately crafted object d’art remind us theveryday life—at least in certain Colonial, Victorian homes; and as evidenced in the Hume galleries, features post-1900 designs from modern and early post-modern period homes—was an ongoing celebration of artisanship and beauty-in-the-hand.

The Art of the Ancient Americas gallery was inspired by the legendary Yale professor and art historian George Kubler, and a gift by Mr. and Mrs. Fred Olsen, in the 1950s, of a collection of Mesoamerican artifacts. The gallery has art holdings of Maya and West Mexico cultures numbering 1500 objects, crossing cultural boundaries from the Olmec to the Inca, and spanning 3000 years. The exhibition animates with the peoples and cultures long-extinguished by war, migration, and most tragically, disease and genocide borne by European invasions during the Age of Exploration.

Highly-individualized character and personal traits seem to come alive in the perfectly-preserved detail found in many works: A rare early Maya male figure carved from a manatee bone reflects the simple elegance of Olmec style. Painted clay Jaina figures of captive men and women, priest, warriors, and a mother holding her baby are laden with details of costume and dress. An exceptional early classic Maya lidded vessel (gift of Peggy and Richard Danzinger, `63), has feet in the shape of peccary heads that support a bowl symbolizing the cosmos.

Old and new are combined in the gallery, in the form of a contemporary watercolor reconstruction of a celebrated Maya wall painting from Bonampak. Not to be missed is the Head of Macuilxochitl [(God ofPleasure, Games and Music ) Aztec, c. 1500, A.D., bequest of estate of Alice M. Kaplan], see right, greets the visitor at gallery’s entrance. Contemporaneously attired in a playful, asymmetrical headdress, he reaches across the ages, inviting us to recall that there is no distant past, just a continuously-evolving present.

Details too numerous to mention had to be addressed before the three-building complex could be considered ‘up to code’ for public safety, interior environmental stability and display space flexibility. Every effort was made to preserve architectural detail long-obscured by decades of re-appropriation of space. For example, the Street Hall tower, affording a stunning view of the Yale campus was uninhabitable in its original form.

The Ennead architectural team designed a building-within-a-building—a structurally-sound ‘filler’ that would provide usable space within the confines of the tower—without relying on its outer stone façade for support. Wide, well-lit stairwells now lead visitors from one floor to the next within the formerly unusable tower space. Additionally, the original glass skylight on the roof of the Old Yale Art Gallery was removed to make way for a discreet, rooftop glass and steel galley space with its own skylight. It is discreetly set back from the building’s top edge, leaving the aesthetics of the original, elaborately-detailed structure undisturbed, when looking up at the building from street level. This also allowed for the creation of the walk-out, rooftop Margaret and Angus Wurtele Sculpture Terrace, with works there by Moore, Maillol and others (and more stunning views of the city).

The Yale University Art Gallery is a destination that makes a trip by train or car from New York City well worthwhile. Not only are the museum‘s no-cost offerings on a scale and quality that rivals the best that any mid-sized museum institution can muster (New Haven in now second only to Washington D.C. with free access to a wide range of art), but the design of the newly-integrated space is masterfully done and worth the trip, as well.

No long lines or ‘artist of the century’ retrospectives here; no crowded gift shops with trendy French Impressionist-emblazoned shopping bags conspicuously displayed. The various galleries present over 4,000 works of art and artifacts in an accessible way, and with enough depth in each collection to truly educate and inform.

Leave time to partake of New Haven’s wide-ranging restaurants for a taste of the world, visit the other galleries springing up all over town and walk the Yale campus, itself, offering just a touch of European-style academic institutions of olde.

Reposted with permission of Richard Friswell and Artes Magazine.