Sophisticaled Giant Dexter Gordon

Insightful Bio of Tenor Titan by Maxine Gordon

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 15, 2019

SOPHISTICATED GIANT

The Life and Legacy of Dexter Gordon

By Maxine Gordon

Illustrated. 279 pp. University of California Press. $29.95.

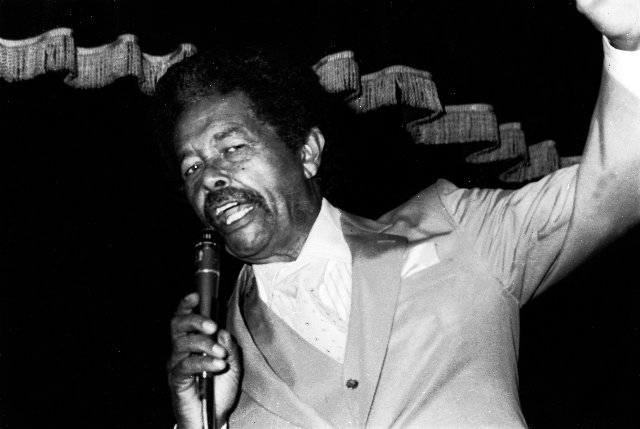

Long and tall, with a laid back, slurring, gravvely-voiced, hipster patois the elegantly attired Dexter Gordon (1923 to 1990) interacted intimately with audiences. After poignant ballads, in a manner boosted from Lester "Prez" Young, he hoisted his tenor in a horizontal manner as recognition of often adoring audiences. They were absorbed by performances redolent with the pathos and poetry of lush life in every sense.

In 1972, during a week in Copenhagen, I was fishing for a story to bring back to the daily Boston Herald Traveler. I copped the number of an expat, bop, tenor sax player from the phone book. During a set at the Newport Jazz Festival I had caught a glimpse of the imposing 6’ 6” musician.

That morphed into a rocket fueled psychedelic lunch which previously I have recounted.

Since 1962 while in exile from the man, and the mainstream. Dexter's reputation as a bop progenitor had long since lapsed. Although he annually visited family and friends in LA, where he was born the son of a doctor, he was out of sight and out of mind.

When we met he had been in exile for a decade but worked an extensive European jazz circuit. That included tours and extended club dates at Montmartre, in Copenhagen, Blue Note in Paris, as well as dates in Scandinavia, Spain and Italy.

In Europe mostly he was clean but there were a lapse when recording "Our Man in Paris" for Blue Note with pianist and fellow addict Bud Powell, drummer Kenny Clark, and bass player, Pierre Michelot . He was busted for dealing, a serious charge, which got knocked down to using. There was a similar snafu in Sweden. That complicated getting a permit to reside in Denmark which had become his home away from home.

Four years after I met Dexter, in 1976, his manager/ wife Maxine Gordon convinced him to leave Copenhagen, where he had a Danish wife and children. They undertook a difficult and risky comeback in the States. It snowballed into a triumph including a contract with Columbia Records and its potent marketing muscle.

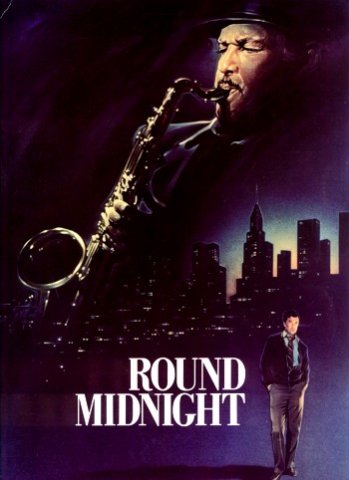

Suffering from emphysema he was semi-retired when Bertrand Tavernier cast him, more or less to play himself. as an American in Paris, Dale Turner. He had a gig playing at the Blue Note in the 1986 film "Round Midnight." The title derives from the title of a Dizzy Gillsepie standard. The character he portrayed, which earned an Academy Award nomination, conflated tenor player Lester Young and pianist Powell during their Paris years.

It took intensive effort to get up to speed after a lapse of rehearsing and performing. The film conveys the ambiance of fleabag hotels, lonely days and melancholy nights. Maxine conveys that he had a hand transforming the script from French parody of a black musician to realistic dialogue. Dexter's prose was more like the elegant manner of Duke Ellington than a blues singer. There was no jive in talking with Dexter. Like Miles Davis, the son of a dentist, Dexter's father was a prominent physician. They were articulate and educated men.

Yesterday, as part of research for this review of Maxine Gordon’s meticulous and galvanic book, I viewed the film which I had seen years ago. It vividly recalled the laconic, melancholy, ennui and duende of a magnificent musician I experienced many times during the decade of his comeback.

The enduring aspect of a somber film is the generous footage of performances with a variety of superb musicians. The band at the recreated 1950s Blue Note is fronted by pianist Herbie Hancock who scored the film. The film features performances by Gordon, Hancock, Freddie Hubbard, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, Bobby McFerrin, Pierre Michelot, Billy Higgins, John McLaughlin, Chet Baker, Bobby Hutcherson, Wayne Shorter, Lonette McKee, and Cedar Walton, most of whom appear in the film. Hancock won an Academy Award for Best Music, Original Score.

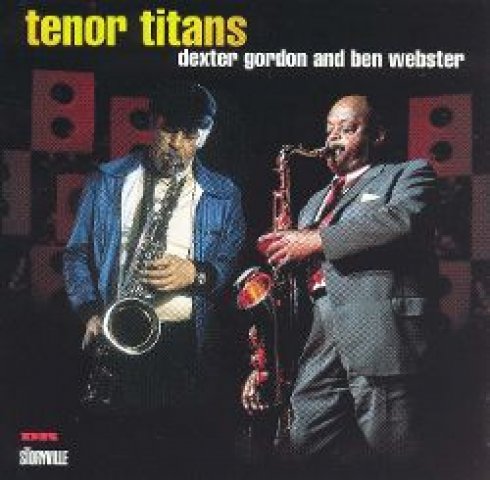

It is a fitting musical document and portrait of late period Dexter when his best work comprised mid temp bop and uniquely lyrical approach to standards. That reflects the breathy manner of Ben Webster, Duke’s tenor master, and Dexter's friend in Copenhagen. Webster died in 1973 and Dexter bought his horn emulating its unique tone. The other sax fetish that the film quotes is "happiness is a wet Rico reed."

From Prez, a generation before Dexter and Basie’s lead horn, he learned to respect lyrics. That equated to singing ballads through your sax. In concert he often introduced ballads by reciting lyrics before playing them. It's well know that Dexter regretted never filling Young's chair in Basie's band. But Count told him that he couldn't afford him and that there "Can only be one leader in my band."

Other than sides with Helen Humes and Jimmie Rushing it is surprising that such a lyrical player rarely backed vocalists. In the film he performs with Lonette McKee a singer I was unfamiliar with.

Reading Maxine’s magnificent study of a major musician and innovator has been an adventure and challenge. It provides a template to consider a range of social and political issues as well as impetus to explore five decades of music from sanguine outbursts of hard bop in the 1940s, through the melancholy, soul searching introspection of his altestijl.

When they were retired and living in Cuernavaca, on pads of legal paper, he was writing an autobiography. Passages of that work, in italics, appear intermittently in the book. He made her promise that she would finish the project. Pages leap into overdrive when we read hot licks of his molten prose and dead on anecdotes.

Remarkably, to do this, she went back to school to study oral history and African American culture. In addition to meticulous research she brings experience and insights as a road manager and professional in the music industry.

Initially, she was hired to get Dexter from point A to point B on tour in Europe. With her head buried in train schedules he quipped asking if that was the only book she ever read? Early on, she proved herself by getting him from Lyon back home to Copenhagen during a railroad strike.

Life on the road is full of temptation from booze to broads. After a night of playing and drinking it’s tough to come down, get some sleep, then commute to the next gig. Coping with that too often entails cycles of uppers and downers. That’s tough on relationships, family and marriages.

Dexter is survived by six children. In the film there is a scene when his fourteen-year-old daughter comes to the club. Another scene entails their awkward reunion in a restaurant. The difficult estrangement is a metaphor for failed parenting. Arguably, the child Dexter knew best was Woody Louis Armstrong Shaw III, Maxine’s son with trumpeter Woody Shaw. Dexter's stepson wrote the afterword for the book. During his return to America Shaw and Gordon often performed together and comprised an extended family.

One senses that after decades of addiction and chaos, including busts and extended incarcerations in the 1950s, Maxine brought order, focus and stability to his life from the mid 1970s. Initially as road manager then lover, wife and manager she was with him every minute of every day. That’s a huge part of getting if not straight at least straighter. For many jazz artists I knew and interviewed there was a revolving door of opiods, pills, reefer and booze. There was a complex delusion of seeking a balance of lesser evils. That meant dipping, toking, and taking a taste.

Keeping up a buzz also meant maintaining a teflon sheild of ironic, ultra cool. That hipster veneer of apathy when intereacting with Dexter was his serio-comic way of fending off the jive, barbs and insults of racist America. That well layered armor was often rolled back when he bared his soul while grooving deep into a ballad. He could find the deepest levels of pain and insight in seemingly trite. tin pan alley tunes

For Maxine, taking over personal management, arranging tours and contracts represented an enormous learning curve. Through her writing about that process we have invaluable insights to the cutthroat music and recording industry. Initially, promoting a then forgotten musician was next to impossible. Major jazz clubs and festivals were reluctant to give prime spots and front money to an obscure, forgotten tenor player.

In the final years, after the film and Oscar hype, Dexter while on tour was treated like royalty. After years of hard luck it was too little too late.

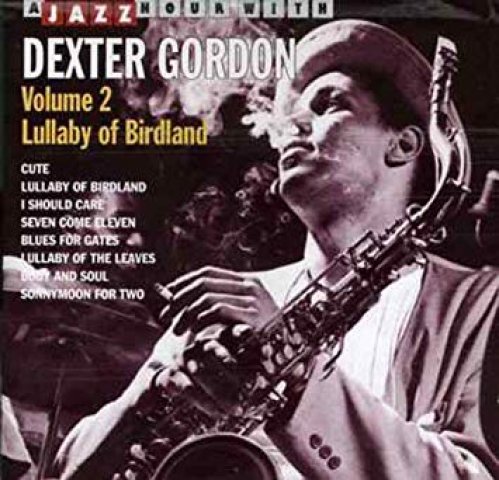

With her book as a guide we break down the Dexter conundrum and discography into phases and challenges. There is an enormous amount of material to deal with. I have been sampling some 20 CDs and as many LPs.

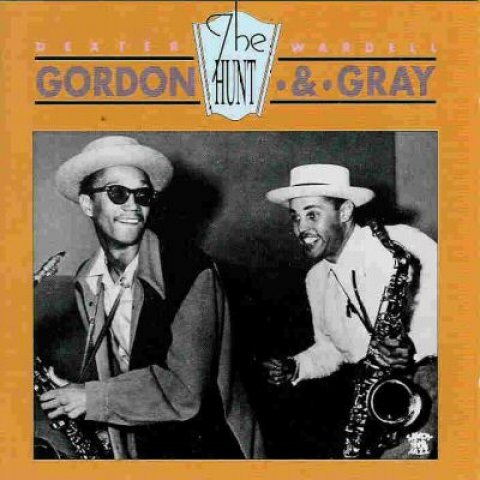

There are the Dial and Savoy 78’s from the 1940s. These are three minute cuts, The seminal duet with Wardell Gray “The Chase,” from 1947, was released on both sides. It outsold Parker’s Dial recordings. There are some extended tracks available from primitive tapes of night club dates.

When long playing records, LPs. were introduced by Columbia Records in 1948 the initial intent was to record classical music. Producer George Avakina began to record jazz artists and set up to tape live sets of the Newport Jazz Festival. Norman Granz released his Jazz at the Philharmonic series. This was a decade after the development of bop the the first time that fans could hear extended solos and jam sessions.

There's not much on record of Dexter from the 1950s. Dexter refused to discuss that lost decade which Maxine has researched. From the 1960s we have several wonderful Blue Note recordings. We learn that producers focused on accessible material. From Blue Note he moved on to notable albums for Prestige.

When Maxine was negotiating with Columbia there was the matter of a binding contract with SteepleChase a Danish label. It released live sessions at Club Montmartre with Dexter and other artists.

Gordon signed what was assumed to be a friendly handshake deal. SteepleChase was founded in 1972 by Nils Winther, who was a student at Copenhagen University at the time. Dexter wasn’t the first or last musician to be cheated into a lopsided contract. Most musicians were paid short money for sessions and never saw any royalties.

We learn of complex arrangements for Columbia to buy out the SteepleChase contract. While a relatively obscure label SteepleChase has an enormous inventory of live material. That allows for an in depth hearing of Gordon with various combinations of expat American as well as superb European and particularly Scandinavian sidemen. A frequent group in Copenhgen featured Gordon with the American pianist Kenny Drew, bass player Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen and drummer Albert "Tootie" Heath. American audiences heard the remarkable bass virtuoso perform with pianists George Shearing and Oscar Peterson. He was noted for keeping up with Peterson the fastest pianist since Art Tatum.

The book encourages us to consider two relatively underappreciated loci for jazz innovation. Dexter came out of LA and the early recordings offer tantalizing glimpses of that milieu. From 1962 to 1976 we are immersed in the European jazz world which deserves further study and appreciation. It is wrong to regard it as a sidebar of mainstream American jazz.

We would like to know more of the unique friendship between Dexter and Ben Webster. I have been able to find just one CD of them collaborating but it is evocative and intriguing.

He was a high school kid when he took a chair with the Lionel Hampton band. Back then there were no conservatories for young jazz musicians or Berklee College of Music. You went to school on the road picking up charts and sharing riffs. From Hamp he moved on to Satchmo. It paid well to be on the road with the master but the music was a snore.

Things opened up with the legendary Billy Eckstein band that spawned bop. He was grooving on slightly older bandmates giants. He learned from Charlie Parker on alto sax and the ear splitting speed and upper register of Dizzy’s horn. Blakey played drums and Sarah Vaughan was the chick singer. From 1943 to 1947 it was America’s most progressive band.

It is said that Dexter transposed bop to tenor sax. In that regard he was an influence of Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. Later, when they matured, he borrowed back. Maxine tells of a falling out with Webster because of that. Ben played mainstream swing. During a gig together he laid down his solo then left the stand to Dexter who followed with a Coltranesque set. Feeling hurt and insulted it took years to repair the rift.

Bop was spawned by cats who cut the draft during the big one. Materials for recordings were scarce during the war years. Add to that the ASCAP strike of 1942-44. To get around it musicians recorded standards with lapsed copyrights and under assumed names. Parker recorded as Charlie Chan and Dizzy as John Birks (his middle name).

For all of those reasons, from addiction issues in the 1950s, then exile in Europe from 1962 to 1976, Dexter never got his due. We have only glimpses of the era when he was in the forefront of jazz invention. Until his comeback other tenor players- Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Trane- filled that void. There is an interesting comment that all of the tenor players, including Dexter and Coltrane, wanted to sound like Getz. Or, in the earlier period, like Hawk when Coleman Hawkins was the gold standard for tenor players. Hawkins also spent many years in Europe where he and Gordon crossed paths.

Often the best of Gordon is heard during jam sessions and battles with other players. That started with running buddy, Wardell Gray, in "The Chase" and "The Hunt" from 1947. In 1955, just 35, the body of Gray was found in the desert near Vegas with his neck broken. There are also great duels with reed men like Gene Ammons, James Moody, and Jackie McClean.

More than just a formidable physical presence, in every sense, Gordon was a giant. He was brought down by decades of stress and neglect when opiods were punished as a crime rather than treated as a disease. That was exacerbated by racism that targeted black musicians. In New York musicians with criminal records were denied cabaret cards. Gordon and a generation of jazz giants were inmates at Federal Medical Center, Lexington, Kentucky. Because they were prisoners there are no recordings of their legendary all star bands. From 1953 to 1955 he served time at Chino Prison as well as Folsom Prison. Always philosophical Gordon regarded prison as getting off smack.

It is often noted that Dexter had movie star looks. That paid off late in life but early on he was noted for acting chops.

He appeared as a member (unaccredited) of Art Hazzard's band in the 1950 film Young Man with a Horn. He appeared in an unaccredited and overdubbed role as a member of a prison band in the movie Unchained, filmed at Chino. Gordon was a saxophonist performing Freddie Redd's music for the Los Angeles production of Jack Gelber's play The Connection in 1960, replacing Jackie McLean. He contributed two compositions, Ernie's Tune and I Want More to the score and later recorded them for his album Dexter Calling.

During Spring break from college in 1960 I saw the Living Theatre production of The Connection. All these years later I vividly recall the experience

Dexter read voraciously including Victor Hugo's Les Miserables in French. In the Tavernier film he speaks hipster French in the manner which I also heard him speak Danish. They were manifestations of his literary passion and fluency.

Maxine tells us that he left his treasure copy of Les Miserables “…to Bruce Wright who was among many other things a poet and defender of the legal rights of many jazz musicians.”

At the time of his death he was working on a script about musicians on the road. There is a nice taste of the Dexter/Maxine project on pages 57 to 61. Some of the characters in addition to Gordon included tenor players, Sonny Stitt and Gene Ammons, baritone, Leo Parker, trumpet players Dizzy and Fats Navarro, singers Eckstine and Sarah Vaughan and bass player Tommy Potter and drummer Art Blakey. What an incredible jazz film that would have been.

It was just another aspect of a multivalent genius. Dexter cast a long shadow over American music from its greatest era.