Dishwasher Dialogues, Theatre of Mischief

Looking For Samuel Beckett

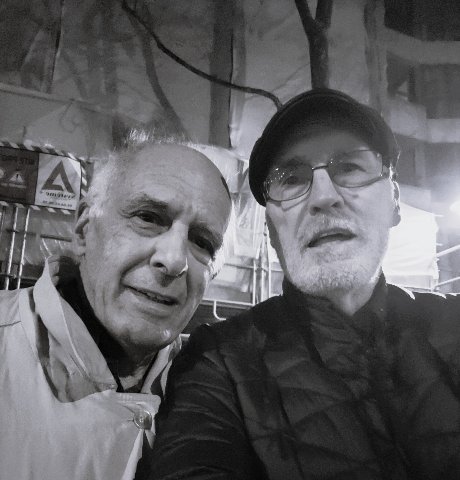

By: Greg Ligbht and Rafael Mahdavi - Jan 16, 2026

Dishwasher Dialogues, Theatre of Mischief

Looking For Samuel Beckett

Rafael: Working at Chez Haynes was a leap in the dark, unexpected, an everchanging tableau vivant. It was theatre in so many ways, with no rehearsals. Every night brought something unexpected. With a little tweak here or there, drama could unfold.

Greg: Improvisation dominated. And sometimes a more brazen intervention helped: a note in the salad here, a shameless reservation prank there.

Rafael: From the moment one walked in through the saloon doors, the place became a stage. There was even the raised alcove over to the left in the back.

Greg: The incomparable table five, slightly elevated, on its own platform. The best table in the house. In the 50’s and 60’s that ‘stage’ hosted some of the best musicians in Paris. Our performances were different, more personal indulgence than anything else. The theatre of mischief might be a kinder description. Whatever, they were frequently ludicrous, even absurd, but always fun. Well, almost always.

Rafael: All of us had been thrown there, and we seemed to know what we were supposed to say. We were rarely at a loss for words, we were “on”, it was “show time”. I dislike Heidegger intensely, but his idea of “Geworfenheit”, being “thrown” into existence and being, applies here.

Greg: His life was the opposite. He never repented or apologized.

Rafael: He was a fucking Nazi party member until the very end when the American GIs were crawling up his arse.

Greg: But ‘thrown into mischief’ appeals. Although Heidegger would not get it. The evil he was thrown into, then embraced, was not mischief and certainly not fun. Not even human. Except in the worst way possible.

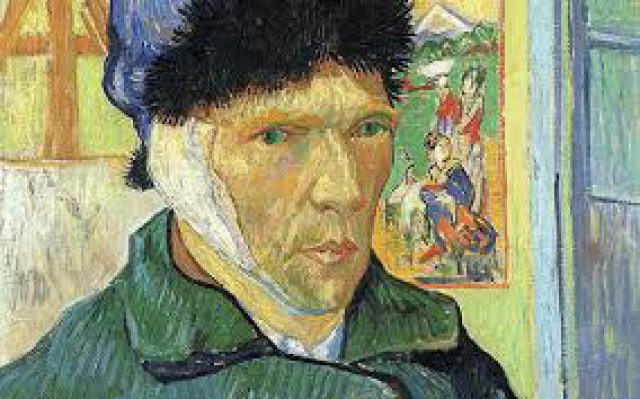

Rafael: We had all been thrown together at Chez Haynes. In retrospect theatre was unavoidable. Theatre seemed to pop up often, outside Chez Haynes too. I recall a dinner at Bentley’s where one of his friends, a crazy woman, tried to cut off my ear. She thought I was Vincent. She was trying to remake art history. I pushed back my chair just in time and she fell to the ground.

Greg: You were talking about Van Gogh. Passionately as you always talked about art. I don’t remember you saying anything particularly provocative, but she suddenly lunged at you. She snarled out something like ‘You want to be Van Gogh?’ and then the knife came out. I think wine played a part. But not the whole part.

Rafael: Back to Chez Haynes. Leroy was an actor; we all knew he had acted in films. The film or play we were in every night was unrolling and nonstop. We had no idea what séance we were in.

Greg: Just to be clear, you are talking about the French meaning of séance here, meaning a sitting. We were not summoning up the dead.

Rafael: Yes, the midnight show. Walk right in, folks! You’ll be an extra. The plot? No idea.

Greg: In this we were following Leroy’s lead. Leroy was the tsar of impromptu. He did not emerge from the back that often, but when he did—because a few friends or some self-styled ‘bigwigs’ were in town—it was an event; generally powered by drink. He would make his entrance from the back, crossing through the room to the bar murmuring preposterous comments in a medley of theatrical snorts and grumbles and huffs. Sometimes he stopped to make a sarcastic comment or give a mocking hello. Always followed with laughter. I especially remember a group of four impeccably dressed, wealthy black businessmen from New York who knew about the legend of Leroy and wanted to meet him: ‘Leroy Haynes!’ they insisted with reverence. When I relayed the message to Leroy—he was peeling onions in the back—he told me to tell them he wasn’t in and wasn’t coming in. Finally, after their third or fourth insistent plea, he came out dressed in full costume, his faded pink tee shirt, casual trousers combo, pulled up a chair, accepted their offer of a drink and plied their ears with increasingly louder and raunchier stories. All to their wild delight. Leroy knew his audience. The restaurant’s best bottles flowed, the anecdotes flourished, and the laughter exploded. Everybody was thrilled and overjoyed. It was pure unadulterated ‘theatre of Leroy’.

Rafael: We would talk about theatre during our Sunday night Chinese dinners. With a few extra Tsing Tao beers, we discussed Martin Esslin’s Theatre of The Absurd, dissected playwrights such as Ionesco, Albee, Genet, Beckett, and poets and philosophers too.

Greg: Those were all-in seminars: poetry, art and philosophy, but theatre was a favorite. There were so many theatres in Paris then—of the absurd, of death, of cruelty, of the oppressed. We would endlessly discuss them, and not just in our Sunday Chinese restaurant near L’Odéon or in Le Trafalgar, or after ‘performances’ at Chez Haynes. They broke out wherever we were.

Rafael: I had read somewhere that Beckett lived on the Boulevard Saint Jacques.

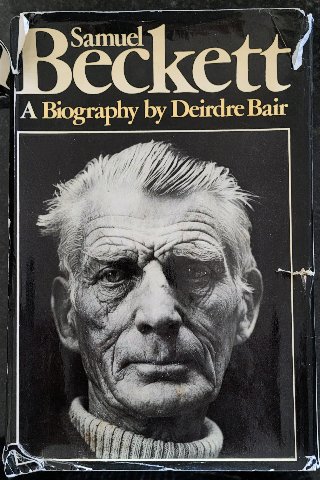

Greg: I think I mentioned it to you. I remember we talked about our heroes— you talked Picasso, I talked Beckett. I was a huge Beckett fan back then. I still am. He was about the age we are now. We knew he lived in Paris, but his address was a well-kept secret. Even by his first biographer, Deirdre Bair, who kept the address to herself. Bair published her biography of him in 1978 and I immediately bought it. I forked out what felt like a fortune for a hardcover copy. It was many, many years before I bought another hardcover book. But for Beckett? I didn’t want to wait for the paperback. She did mention him living on Bd. St. Jacques. There was no specific address given, but there were clues. I cannot remember all of them, but there were enough hints to give an accurate idea of the building’s location. It was near a Metro stop, which had to be Metro Saint Jacques, and she commented that his view looked down into La Santé Prison. He was in the 14th arrondissement, so not far away from me.

Rafael: One Sunday you and I started looking for Beckett’s apartment. We began at Place Denfert-Rochereau and worked our way east, toward Place d’Italie. In those days, you’ll remember, there were no codes required to enter apartment buildings.

Greg: Not the outside door anyway. Delivery people still had to deliver.

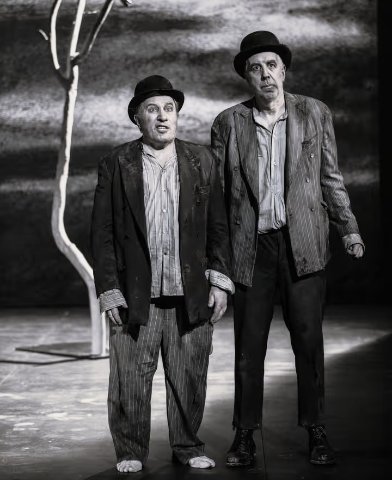

Rafael: We told ourselves that this search was absurd.

Greg: But not Godot absurd. We were not simply standing on the street, waiting to get lucky. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist the gag.) I had done my research, such as it was. Today we might be called stalkers. On second thought, maybe absurd would have been appropriate. We were searching for the author of Waiting for Godot after all. And, we had no real idea what the point of doing so was, or even how many buildings we would have to try. (Now, as I write this, I am suddenly feeling a bit uncomfortable; a forlorn image of Vladimir and Estragon farcically standing on Boulevard Saint Jacques in my mind.) The irony never occurred to us back then.

Rafael: The Boulevard Saint Jacques wasn’t that long, it ended at Rue de la Santé. I forget where exactly, and after three or four attempts, we walked into a lobby, and read the names on the mailboxes. And there it was. Samuel Beckett.

Greg: It was not very many attempts. Two or three buildings at most. The clues worked. But the name was not Samuel Beckett, it was “S. Beckett” on a metal mailbox, in a bank of 16 or so similar mailboxes, on the righthand side of the foyer as you entered.

Rafael: I suggested we ring the buzzer, but after much discussion, we didn’t ring. I changed my mind; it seemed invasive.

Greg: It would have been invasive. Totally. Still, maybe we should have.

Rafael: Maybe Sam would answer the door and tell us to scram. Although I read years later, he was an amiable man; he would probably have talked to us a short while.

Greg: He only lived about 15 minutes’ walk from me. I contemplated just passing by on occasion and waiting around to see if he came out. But I never did it. Not once. It was enough to have located him. To know he was nearby. So, I wasn’t much of a stalker after all.

Rafael: I saw Beckett once, a few years later, at the bus stop on the Rue Dauphine. I was standing next to him and didn’t dare say hello. I told myself every Parisian intéllo must walk up to him and say something weird or silly or even nice. I was sure he’d heard all the variations. I said nothing. I didn’t wait for the bus. Much later somebody who works in the theatre told me that Ionesco, who also lived in Paris at the time, was lonely in his old age. He would call his publisher Gallimard to inquire if anybody had called for him. Despite his fame and his contributions to the theatre he was alone; he needed people to talk to, to know that some people enquired about him and hadn’t forgotten him.

Greg: For all but a few, that is the writer’s lot, the artists’ fate. Even the celebrated are lonely in the grave. Of course, some—I’m looking at you Nietzsche—live posthumously. But that only has meaning during the fleeting days of pre-posthumous life.

Rafael: Thinking back to those times and our numerous discussions, I realize that we were relatively isolated. We had come to Paris with no letters of introduction, we knew nobody in the theatre or art world in Paris. We had arrived in Paris cold, with no connections of any kind to people who might appreciate our intelligence and gifts.

Greg: When I first arrived in Paris, rumors of intelligence or special ‘gifts’ would have been greatly exaggerated. As they would today.

Rafael: I wouldn’t go that far, mon ami.