Show and Tell (and Play) with Philip Glass at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

The Great American Composer Returns to North Adams

By: Larry Murray - Jan 17, 2009

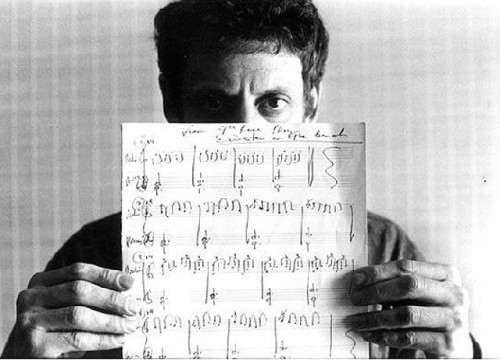

The American composer Philip Glass returned to Mass MoCA last night for an evening of reflections on the music and films that comprise his most recent oeuvre. He was introduced by MoCA's Director, Joe Thompson. Over the course of two hours, in conversation with the noted Boston Phoenix film critic Gerald Peary, he elaborated on the hows and whys of his musical choices, and revealed a bit about how he creates his music.

For all his fame, Glass is not a flashy showman. Though born in Baltimore which also produced filmmaker John Waters, neither his music nor his persona are particularly flamboyant. Indeed, the evening at Mass MoCA was more like a classic show and tell with familiar subjects than a real look into the man who is, arguably, America's greatest living composer. The applause at his arrival was just as enthusiastic as at his departure. He was preaching to the choir.

Wading through the enormous body of work he has created over his lifetime - he is now 70 - one finds operas, symphonies, chamber works and numerous collaborations with playwrights and choreographers. There has been much speculation as to why such a prolific composer of challenging works came to spend the latter part of his life writing music for film. The quest for fame seems unlikely. Perhaps it was the easy money (compared to writing grant requests and negotiating with orchestras) or perhaps simply the creative challenge itself.

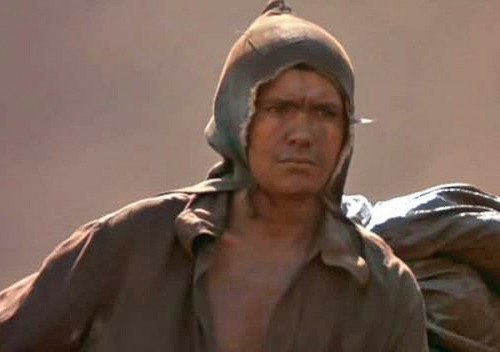

Glass revealed his fascination with the process of creating film, and his insistence on being part of that process, rather than the latecomer who simply adds music underneath an already edited final work. The first film his interviewer, Gerald Peary highlighted was Powaqqatsi (1988) from the Qatsi series which he worked on with the political filmmaker Godfrey Reggio. Glass told the MoCA gathering that he was able to travel to Brazil with the film crew where they documented the 8,000 young fortune seekers mining for gold in a gigantic open pit, each owning a 2' x 6' piece of it. During the shooting, the cameraman was listening to the score, as did some of the people being filmed. Glass spoke about how simple and child-like the gold diggers appeared to be, and how, upon returning to the United States, he added a children's choir to the score he created to reflect that.

Also screened was Reggio's Evidence, a short seven minute film of very young faces in rapt attention...but to what was not revealed until the very end. They were totally immersed in simply watching television.

It is clear in these documentary films how the undulating, hypnotic music of Glass can work to bring the viewer closer to the images, and thereby develop a closeness between viewer and viewed. Another example Peary chose provided the opposite effect. In The Thin Blue Line, created with Errol Morris, 1988, the music acted to distance the viewer from the horrendous murder of a policeman taking place. In The Hours, the suicide of Virginia Wolf is shown, again, with the music setting a more nostalgic feeling, rather than one of horror.

Long after the completion of Tod Browning's film Dracula in 1931, Glass added a new music score for the DVD release. He admitted that it was the close-ups of Bela Lugosi's fanged face that drew him to the project, having spent many afternoons as a child in the dark of the cinema.

The show and tell portion of the evening also highlighted excerpts from Cassandra's Dream (Woody Allen, 2007) and with whom he had artistic differences, and Kundun (Martin Scorsese, 1997) with whom he didn't.

The basic question of why he has been composing for film in the latter part of his life was never answered.

The final portion of the evening found Glass at the piano, playing a number of his works. Though the specifics were not noted on the program provided, Glass mumbled that they were his Etudes 2 and 10, as well as excerpts from Jean Genet's The Balcony. Glass prophesied that we would find them very similar, and we did.