Felrath Hines (1913-1993): Out of the Shadows

Three Works Acquired by the MFA

By: Susan Schwalb - Jan 20, 2010

"I started painting to give myself a better life. I couldn't find a handle with my name on it. I wanted something to do, something that was worthwhile and manageable. I do not want my work to be placed in a special category with a particular group. ….I should be able to show wherever I want to show and under the circumstances I prefer to show." –from an interview with the artist in 1989 by William E. Taylor, published in "The Abstract Art of Felrath Hines: Icons of a Perfect Neutrality" International Review of African-American Art, Vol. 10 No. 3, 1993.A luminous painting, Untitled aka Grey and Ochre, 1977, by Felrath Hines (1913-1993), was exhibited in the West Wing at the Museum of Fine Arts/Boston from July to December, 2009. The work was installed on the second floor, between a large wall painting by Kara Walker, and David Smith's Cubi XVIII, a polished stainless steel sculpture. The Hines painting had been recently donated to the museum by his widow, Dorothy Fisher, along with two other abstract paintings by the artist.

I first saw this elegant work in early October, 2009, as part of a backstage tour of recent acquisitions. Made up of very simple geometric forms with softened, blurry edges between the colors, it seemed to project a muted light from its core. The subtle grays and ochre's appeared to change color from a darker tone at the top to a lighter tone at the bottom as if dividing the work between dusk and early dawn. The piece was a dramatic contrast to the Kara Walker painting, The Rich Soil Down There, an enormous black and white caricature of southern culture and slave life. This blunt, in-your-face work about the African-American experience was at the opposite pole from Felrath Hines' interests. On the other hand, the Smith sculpture seemed engaged in a continuous dialogue with his painting, as it echoed its horizontal central band.

I was inspired after my visit to the MFA to learn more about Hines's life. I began by looking around the Internet, after which I visited Dorothy Fisher at her Brookline home, filled with works spanning Hines' career. Later that day Dorothy took me to her daughter's house where an attic space had been converted into a studio to hold the rest of the estate. This has become a place to invite curators and collectors; in the past few years Dorothy has written to more than 50 institutions, where Hines had exhibited or had a connection, offering to donate 3-5 works. The response was immediate and enthusiastic, and apart from the MFA, paintings and drawings are now included in more than 30 museums and university collections, including the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts/Houston, the National Museum of American Art, Yale University Art Gallery and the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Felrath Hines was born in 1913 in Indianapolis; his father worked as a waiter and his mother as a seamstress and teacher. He was the oldest of six children, although only four survived. As a child his mother encouraged him to explore all the opportunities that could be found in this segregated city. Although he couldn't go to the movie theaters or swim in public pools, he was able to take art classes at the Herron Art Institute in downtown Indianapolis which, unlike the public schools, was open to all races.

After graduating from high school he worked at many jobs, managing an ice cream parlor, for example, or cleaning yards, until he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps where he fought forest fires in the West while taking correspondence courses in art.

In 1940 he became a dining car waiter on the Chicago Northwestern Railroad, in those days one of the best jobs for an Afro-American. After several years he had built up enough seniority to arrange his schedule so that he was able to go to the Art Institute of Chicago during the day while working on the railroad at night.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like for a young art student to have a schedule that involved traveling most of the night. A few years later, Hines moved to New York City to begin his career as an artist. Initially he worked as a waiter, and then as a fabric designer and china painter, but he also took evening classes at Pratt Institute as well as private lessons with Nahum Tschacbasov, a Russian expressionist cubist painter.

By 1951 he was working for the framer Robert M. Kulicke where he met many well-known artists of the day and eventually became a partner with Kulicke. At that time it was almost unthinkable for an artist to make a living from art, and although Hines began to exhibit at serious galleries, he sold very little. He had his first museum exhibitions in 1955 at the Riverside Museum, NY and the John Herron Art Institute (now the Indianapolis Museum of Art).

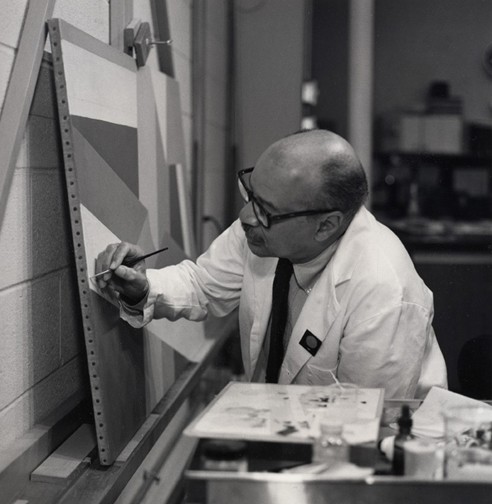

While working at Kulicke, Hines became interested in art conservation and restoration, and eventually devoted two years away from his own work to serve as an apprentice to Caroline and Sheldon Keck, pioneers in conservation. During this time he worked on the Monet water lilies at MOMA along with the O'Keeffe-Steiglitz collection for Fiske University.

Leaving Kulicke, he began what would be a 25-year career in restoration, first in New York as supervisory conservator at the Fine Arts Conservation Laboratories, and then in private practice with clients such as The Whitney Museum, the Corcoran and MOMA. At the same time he became O'Keeffe's personal restorer, and in 1972, at O'Keeffe's suggestion, he relocated to Washington DC to become chief conservator at the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian.

This would be the first time he had paid vacations, and the chance at a pension. He restored such iconic paintings as Gilbert Stuart's portraits of George and Martha Washington, and in 1980 he was appointed chief conservator at the Hirshhorn Museum. Only when he retired in 1984 was he finally able to devote himself totally to his work.

Hines participated in the civil rights movement and knew Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. While living in New York in 1963 he joined the Spiral, a group organized by Romare Bearden that included fifteen other Afro-American artists. They met weekly to grapple with civil rights along with issues related to art practices. Often arguing whether their art should contain social commentary or reflect "the Negro culture", Hines was adamant that it was up to the individual artist, and noted that some Jewish artists reflected Jewish concerns while others did not.

Before the group stopped meeting in 1965, it organized one group exhibition (restricting the palette of the paintings to black and white) but Hines continued to be active in organizations that addressed issues facing black artists and he continued to march in civil rights demonstrations

Even though opportunities to exhibit in the 1960s and 1970s were confined to exhibitions that showed black artists exclusively, his work remained abstract and personal. After his move to DC he was able to find gallery representation with Barbara Fiedler Gallery and the Franz Bader Gallery. Only after his death were there major New York exhibitions of his work at the June Kelly Gallery (2002 and 2004).

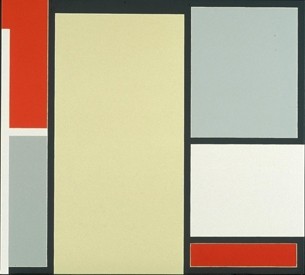

Aside from Untitled, Grey and Ochre, The Museum of Fine Arts owns two smaller paintings by Hines. Transition, dating from 1958, is typical of his early, more painterly abstractions; filled with brightly colored, loosely shaped geometric forms, it seems to evoke landscape. The palette is varied here, but by the 1970s Hines' work became much simpler, with a clearer edge and very subtle colors. Facade I, 1987 a hard-edge, brightly colored painting, somewhat reminiscent of Mondrian, is more characteristic of Hines's late work. The precise edges (made without tape) lose the softness of Untitled as the artist plays with geometric forms and black linear borders. With their bold, intense color and their perfectly crafted surfaces, Hines' late works can only be compared to Anne Truitt's sculptures. I hope that sometime in the future the MFA will mount a full-scale retrospective.

Susan Schwalb is one of the foremost figures in the revival of the ancient technique of silverpoint drawing in America. Her oeuvre ranges from drawings on paper to artist books and paintings on wood panels. Her work is represented in most of the major public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The National Gallery, Wash. D.C., The British Museum, London, The Brooklyn Museum, NY, The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Kupferstichkabinett - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, The Ashmolean Museum. Oxford, UK,Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, The Achenbach Foundation of Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, The Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, and the Arkansas Arts Center, Little Rock, AK.