Marilyn Horne: The Song Continues

Master Class at the Weill Recital Hall

By: Susan Hall and Alison Gardiner - Jan 23, 2016

Marilyn Horne Master Class

Weill Recital Hall

Carnegie Hall

Emily D'Angelo, Mezzo-Soprano; Matthew Swensen, Tenor; Angela Vallone, Soprano; Ian Koziara, Tenor.

Collaborating Pianists: Michael Biel, Alden Gatt, Nathan Harris, Andrew Sun.

New York, New York

January 21, 2016

The Master Class is a high art form, first conceived by Franz Liszt and other European pedagogues who taught group lessons. Liszt was notoriously temperamental. The tone of Terrence McNally’s play Master Class may reflect Liszt, but is unfair to Maria Callas, who taught her students warmly, just as every master we’ve ever witnessed does.

Performers who are also teachers undertake a sacred trust and Marilyn Horne is a high priestess of the form.

Horne moves briskly onto the stage of the Weill Recital Hall, swathed in a blue green silk jacket, but also business like in glasses and picking up a pencil for notes. She is warm, humorous and plain-spoken. She immediately sets a tone of appreciation, speaking with enthusiasm about young singers she's just heard.

Students in this master class are on the cusp of careers as are their collaborators at the piano. The hall is packed with young musicians, older ones and enthusiasts of the human voice. Hearing young talent is exciting. So is watching an artist like Horne make subtle and not so subtle suggestions which yield a more satisfying performance as the students take in her advice and incorporate it in their songs. Horne combines two crucial aspects of teaching well: she is joyous and rigorous.

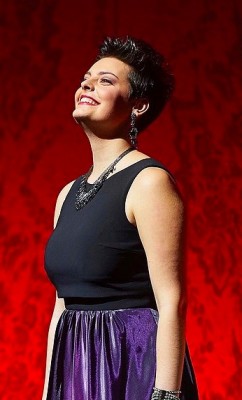

Emily D'Angelo, the first singer, has an Audrey-Hepburn-pixie face topping a long-stemmed figure, imposing and yet delicate. Her lush mezzo voice is displayed in a challenging Gerard Manley Hopkins poem set by Samuel Barber. Horne dives into the unusual and dense words of the song about a nun who will soon take her vows. Horne points out that listeners need to understand the words, which are difficult because they are not often heard. The diction has to exaggerated to make the words clear.

Horne focuses on "sided hail" as an example of how to bring the texture and color of the imagery to life. She asks what the phrase "sided hail" means. D'Angelo guesses, "Faceted." Horne speaks of the hail cutting sideways through the air, slicing. Harsh. When D'Angelo sings the phrase a second time, she captures the world of storm that the nun will soon leave for the veil.

Her rendering of Ernest Charles familiar “When I have Sung my Songs” is wrenchingly touching as she follows Horne's suggestion to plan her breaths to provide for slower pacing. Accompanied by the sensitive Nathan Harris, who studies with Martin Katz at the University of Michigan, D’Angelo already is cast as Nero in the Coronation of Poppea.

Next up is Matthew Swensen, a tenor trained at the Eastman School of Music. Horne comments that all young artists want to sing Strauss these days. Swensen shows us why. Night is full of aching melody accompanied by luscious harmonies. As Michael Biel sympathetically accompanies, Horne directs Swensen through some choice bites on German gutterals and final consonants. Swensen claims his Scandinavian heritage in Edward Grieg’s En Drom. Horne's attention to diction would yield arresting results through the evening.

Angela Vallone also chose Strauss, unleashing a pure and shimmering soprano. Horne questions her interpretation of the song's context which does not seem clear. Is she singing about saying a final farewell to a dying loved one? Yes, Vallone would try that.

Andrew Sun is already a piano collaborator of the first rank. Horne suggests that he play the introduction at a much slower pace than he ever would have imagined. Extending notes until they are almost unbearable, the magic of lento becomes clear. The listener wishes a note would last forever. Particularly a Strauss note. Horne laughs: "When you pass the age of eighty, you want everything to go slower and slower."

Yet when Vallone begins to sing, Horne observes her wiping a tear away. Horne reminds her: Sadness must be communicated in the song and should not interfere with the singing instrument.

Ian Koziara displays a powerful helden tenor edge and lyricism in Wagner's Dreams. Horne clearly loves his interpretation, but counters that Wagner's Dreams is not the place for Siegfried. Kozario smiles in agreement and is able to adapt quickly and give us something smoother and more tender.

Horne zeroes in on Koziara's habit of leading with the chin, as though he is getting his main support from the chin. On a dime, Koziaro relaxes his chin.

Time is running out and the audience is asked if Koziara and his charming and sensitive collaborator Alden Gatt would undertake Schubert. The audience insists. In Erlking, Horne is concerned that Koziaro does not differentiate the various voices. Rosa Ponselle had squealed when she sang the young boy. Horne imitates Ponselle. How can Koziaro a young boy's voice? He does so effectively, a light, heady sound, quite different from the fuller, bolder narrator's.

Horne is a wonderful, detailed teacher and it is a privilege to be in her presence. Clearly these talented singers were able to incorporate her apt suggestions to good effect. Is revelation the reason audiences respond to a great master class? With Horne, the answer is yes.