Langdon Quin at University of New Hampshire

Acts and Memory Through April 8

By: David Carbone - Jan 27, 2010

Langdon Quin is a classicizing realist who, over several decades, has steadfastly held to his own path, one committed to the challenges of both perceptual and synthetic representation. For him, the Western tradition has been open and alive. By immersing himself in the art-past, Quin has been able to fortify himself for the difficult task of developing a language for his experience. At the core of Quin's art is a sense of awe and a deep pleasure in being able to see the world and express it through forms generated out of a late-modernist sensibility.

The necessity of tradition, for Quin, is centered on its capacity to expand the associative emotions and ideas of an image and slow our full recognition of its emotional force. What is gained is the exposition of cultural memory as a gauge to the complexity of individual experience and an exploration of the inherent meanings at play between works of art.

Underpinning everything Quin has done is a veiled autobiographical source, so it isn't surprising that his work evokes the opposite of a direct emotional response; he has always shown a subtle refinement and reserve in revealing his experience of life. At the risk of losing the sense of immediacy, in his major projects, he has gambled on obtaining a delicate poignancy.

This approach was derived in part from his mentors at Tanglewood and Yale: William Bailey, Gretna Campbell, Bernard Chaet, and Gabriel Laderman. All of these artists approached figuration through their understanding of modernism and abstraction; and each arrived at a completely different figurative position. In arranging his own constellation of forebears, Quin has also looked to Piero, Corot, de Chirico, the Novecento artists Felice Casorati and Fausto Pirandello, Bonnard, Balthus, Lennart Anderson, and James Weeks; all of whose influences can be felt in various ways, especially in his landscapes.

Often moving from perception to invention, Quin may begin with a drawing or a "first strike" oil sketch, after Corot's practice, with the principle aim of establishing the space through light. From such spontaneous works, larger synthetic paintings are developed, where more complex structural ideas are elaborated. Quin's desire to dwell deeply in what is seen becomes an extended meditation on landscape, still life, or the figure.

Yet surprisingly, Quin's use of traditional forms does not quite arrive at the old meanings. The Renaissance belief, famously stated by Alberti—that the magic of painting can make the absent present—is reversed in Quin's work; I often feel the tremulous sensation that what is depicted is vanishing as I look. His work has a synesthetic quality, as if gazing through sun-struck, colored chimes, their tintinnabulation signaling a ghostly, almost fairytale vision. This is achieved through his chromatizing object colors by following the laws of simultaneous contrast, deployed with broad, broken touches that dissolve forms into patterns of light. Despite his emphasis on a classical formality, Quin's effort to express an inner calm actually elicits a morbid feeling of panic, of life's —all-too-quick—falling away. This, for me, is the moral kernel of his work.

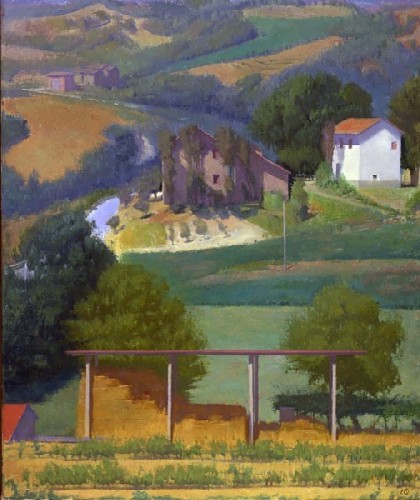

Quin's landscapes also carry political values, and regardless of where he paints, his work implicitly represents an opposition to the destruction of the countryside and the spread of anonymous and vulgar suburban developments. In his work, too, he finds liberation in his solitude before nature—away from the complexity of human conflict. His choice of farm country, in both Italy and America, as a place to live and work can be seen as Quin's urge to dwell in places that convey a sense of an enduring past, of Arcadia. Certainly the very urban hunger for "green" values underlies the appeal of Quin's landscapes.

These works hold illusionism in check through a generalized painterly representation heightened by a prismatic palette of colors. Quin shows himself to be a master of balancing spatial organization and the simultaneous ordering of forms as shapes in the surface. This aspect gives his images a cubist foundation that links his formal concerns with those of Piero, Bonnard, Balthus, and Casorati. Often working with a painting knife, to heighten the material presence of the paint, both as an analogy to the substance of things and as an agent to activate the surface-to-space tensions, Quin pushes his paintings from image toward musical-like structure, and in his best works, to a rapt vision. By lowering the effects of realistic mimicry, Quin is able to give his work a luminosity and effects of luster, a hazy atmosphere of beautifully nuanced tones and color temperatures that veil nature's forms with his emotion.

Although these mostly rural scenes are alternately from Troy, New York, Durham, New Hampshire, and Gubbio in Umbria, Italy, where Quin has spent his summers for several decades, the dominant dialogue is with Balthus's Chassy landscapes. While much of Balthus's dark tenebrous winter landscapes express a spectral existential melancholy, Quin has sought to rival the languid humidity of Balthus's spring and summer views with their golden haze and verdant flora. In Quin's work languor, haze, and greenery express his most ecstatic self and a wistful longing to glimpse the Eden beneath the surface of the everyday wilderness. Landscapes that seem to be major poetic statements are: Upstate Spring: Abandoned Farms (1997), Mills with New Marina (1999–2000), the panoramic Gardener (2000), the multileveled Parish (2004–5), the bird's eye view in Landlines (2005–6), the woman on a ladder, trimming a rose bush in Pruning (2002), and the Near San Benedetto (2009); seen together they begin to suggest a cycle of seasons.

In Quin's hands, still life is often a hybrid genre fused with landscape; various windows capture the most intimate glimpses of interior/exterior spaces. The watering can left on a sill in Window, (2002–3) seems to play a symbolic role, signaling the mundane work of both gardening and studio work. The same can be said for Still Life with Tools (2009) in which the artist is seen in the distance. Other still lifes cast aside the neo-romantic mode to engage with the Italian Meta-physical tradition where the objects seem to represent urban buildings in September Eleventh (2001), Ledge (2006–7), and Seismic Still Life (2005). The latter work seems to blend William Bailey's crockery reliefs with Rodrigo Moynihan's studio shelves in an attempt to play the posed against the spontaneous, his inner calm against the anticipation of a sudden—possibly fatal—event, transposed into the anticipation of a landscape tremor. In these works, cultural echoes serve as a useful counterpoint to historical events and personal crisis, melding still life with narrative.

The least histrionic and more veristic works, in this mode, shade toward the anticlassical qualities of Fausto Pirandello and Lennart Anderson and may yet prove to be Quin's most original contribution to the genre. This is especially so in Still Life with Model's Chair (2006) where the heavily built up surfaces and the seemingly accidental arrangement of silk forms create a voluptuous evocation of the model's absent body, a displaced carnality, which is both mundane and quixotically compelling.

Another major vein of feeling only implicit in his landscapes is the theme of human mortality; and so, evinced in his depiction of family life. An example in one of his major works, a rather abstract case, is La Bottega: A Family Portrait (1996). Here Quin enlarges his ambition by composing a polyphonic pictorial structure of figures and buildings that compels us to rove through the picture's space. As in a traditional allegory, three generations of a family play out their roles that suggest our progress through life, if we live long enough and are lucky. In this Italian context, one has the sense of la famiglia stretching back in time for millennia.

Still what interests me in this painting is less an exegesis of its content than how the subject is situated within Quin's larger vision of nature and his mastery of invention. The unusually long horizontal format of this canvas (52" x 102") does much to decenter its focus, forestalling our ability to take in the picture at a glance. Within this format he has invented strong, laterally sliding, shape-shifting relations that develop into a time-shifting spatial arabesque. This allows us to gradually take in the layers of correspondences that create the objective correlative to Quin's seemingly Stoic view: we are elliptically led from innocence to the crypt and beyond into the radiant matrix of nature.

Autobiography is most pronounced in several ambitious figure compositions that span the last two decades. The earliest is a diptych called, A Studio View (1988–90), in which the figure of the artist straddles the two panels as he leans out a window. In the right foreground, we are given the interior of a studio in which the drama of youthful desire and mortality are echoed in a large painting of a nude woman and an emblematic still life in the lower right corner. The artist has stood up from his work to gaze out from his upstate New York studio at a shaded orphic vision of a woman—his wife—descending a staircase with a young child in her arms. Beyond them an idyllic Italian landscape winds back into the glistening humid distance: the family in Arcadia. Pictorially, everything is opposing sign and symbol; the stairs descend, while the studio ladder rises. It's a pictorial equation of the delicate and difficult balancing between the solitary life of the artist and the community that is family, and ultimately Eros, the force of attraction and havoc. Without pretense, Quin adapts the mechanics of allegory to testify to the truth of his experience.

Recently, the theme of studio life vs. home life has been emblematically restated in the hybrid still life Household (2007), where the studio in the foreground is set against the home, seen through the window. Closely following A Studio View (1988–90) in time is the Visitor (1992–93), in which the artist's wife, then a young mother, sits at a table in their Italian summer home with her little boy. As we look from mother to son, we become aware that the tall nude woman with classical Greek braids standing behind the boy is an apparition that only we can see.

To the boy she is a vague sensation, a frisson—felt as a sudden chill at the back of the neck; to us she is an ambiguous personification. Is this visitation by Venus an amplification of emergent oedipal desire, a family romance in Freud's sense of the term, or is she the artist's nostalgic signaling of his own moment of sexual self-awareness provoked by a moment observed?

However, the unique appearance of this Venus in Quin's painting may also be seen as a dialogue with the work of the artist's wife, Caren Canier, whose imagery has often been concerned with the metaphoric presence of Greek and Roman female deities that have long haunted her experience of living in Italy. In fact, the painting may really be about her sensation.

If the child in Visitor is a mirror of parental imagining, that projection takes on a sense of separation and otherness in Solstice I (2006–8), where the artist's sons loom awkwardly large and uneasy in the Gubbio farmhouse, as their comparatively diminutive mother looks on. The painting has been deliberately left unfinished and the resulting disjunction of form language yields a somewhat expressionistic effect. Set against the spatial interior, a huge X spans the surface from corner to corner, separating the figures into separate zones. Barely contained by the doorway in which he stands, the eldest son seems poised to leave, as the younger son squirms in his chair, a big-headed figure whose features are undefined—schematic, perhaps meant to underline the labile character of his adolescence. Here the tensions of A Studio View fall away as the artist and his wife are as one in contemplation of the maturation and departure of their children, giving double weight to the picture's title.

In Models: An Allegory of Faith (2005–6), Quin has turned to the subject of desire and fidelity. Two women studied separately in drawings and painted studies are brought together in what at first appears to be a conventional pairing of virtue and vice. In the foreground the voluptuous model Sarah is posing seated and set before a screen. To the left, the room beyond opens up to reveal the other figure, the artist Caren absorbed in painting at a table. Between them lies the family pug, standing in as the traditional symbol of fidelity. But the longer one looks, the more alternate readings begin to appear.

As a painting, Models appears to descend from Balthus's Three Sisters series. Quin takes the idea of Balthus's girl in profile and the girl facing out and situates them in an off-square format. Every form is condensed and made to obey a basic geometric pattern in a compressed space. Each figure is absorbed in what she is doing, making no acknowledgement of the other. Yet both are also a reworking of the artist-and-model theme. Perhaps Caren is drawing Sarah from memory? And perhaps, too, the Caren figure represents the artist's anima?

Both of these women are models in a double sense: they have modeled for Quin and they are models of ways of being that he admires. Surprisingly, the older figure of the artist Caren is classicized to seem younger, almost child-like in spirit, while the youthful, zaftig Sarah is depicted in a more realistic manner, revealing a womanly old soul.

Modeling itself is a mode of subtle but visceral collaboration, as models may learn; one is closely seen and radiates a sense of being that can have a decisive effect on the drawn or painted results. When it is successful, modeling is a sharing of intimacy, a mutual exchange, a gifting, which is in itself an act of faith. Here, Quin addresses the primal reality of his desire in manifold aspects.

This essential theme of the demi-urge is also played out in the complex triptych Working From Life III (2005–9), Quin's parting salute to his career in teaching at the University of New Hampshire and an acknowledgment of the progress of his students from their beginnings to the brink of maturity. Like the most recent self-mocking variation on Models in which Quin has included himself, Working from Life is bemused, even wry.

The painting seems to read like a modello for a mural. The experience of space and light changes dramatically from room to room, suggesting different times of day, and different stages in the student's development. Strong diagonals move from corner to corner, carrying my gaze from panel to panel, alternately emphasizing and suppressing space. Each figure is broadly described and conveys its role through gesture.

In the first panel, a grey-blue morning light floods a deep space of diagonally placed forms. Young students in a wide arc variously focus on the animated instruction of the teacher, in a blue apron, while a naked model is suppressed by a shadow emphasizing her as a body, a form to be understood like the cast figures high above her on the cabinet.

By contrast, the central panel functions like a frieze. The room is filled with a yellow amber light suggesting late afternoon and compressing the studio's space. The chorus of students busy themselves setting up the stage for the model, a hermaphrodite, the symbol of the sexes united. Along the sides of the studio, amorous couples, both straight and gay, embrace, almost hidden, in the chaotic procession of figures and easels.

Finally, we see a night class in which nacreous green floodlights illumine the cavernous dark blue-purple interior. The model, a woman, is still central to the image and surrounded by the class, but the students have turned away, absorbed in their painting and themselves, like the artist in Models. In these last two panels, the instructor seems peripheral and melds into the unfolding of activity, like everyone else.

It is a quixotic representation of that second family of every painter-teacher: the class. What comes happily to mind, as I puzzle over this parting souvenir of the life class, are a few lines by the great twentieth-century Italian poet Umberto Saba, which seem to speak directly to what Quin is affirming, in this and perhaps all of his works:

Other than you, what have I talked about

in the practice of my art; what have I hidden

or unveiled other than you?

What would have seemed distasteful to my senses

lacking you, and hateful to my higher spirit,

all that I would have fled from as unworthy of me,

I sought because of you, dark desire.

Nor could I curse you, who are too much

myself: you are the father of my fathers,

the children of my children.

—"Desire" Umberto Saba

Like Saba, Quin cannot help but explore the dark forces driving the pleasure he takes in painting and the empathy his work derives from the sublimation of love. Langdon Quin's unique blend of an American, post-abstract figuration and an Italianate, classicizing taste renders quotidian scenes with a quiet dignity, which nevertheless, reveals a subtle mystery.

David Carbone, University at Albany,

State University of New York

Umberto Saba, "Desire" from The Dying Heart is included in Songbook: The Selected Poems of Umberto Saba, trans. by George Hochfield and Leonard Nathan (Yale University Press: 2008) 313.

Catalogue of the exhibition is available for $15. You may order at the UNH website www.unh.edu/moa or call 603/862-3712.