Herb Snitzer's Glorious Days and Nights

A Jazz Memoir

By: Charles Giuliano - Jan 29, 2011

Glorious Days and Nights: A Jazz Memoir

By Herb Snitzer

Afterward by Dan Morgenstern

144 Pages, illustrated, 2011

University Press of Mississippi

Other Publications

Jazz: A Visual Journey, Notables Publishing

Reprise: The Extraordinary Revival of Early Music, Joel Cohen, Little, Brown & Co., Boston, MA

Today is for Children, The Macmillan Co., New York, NY

Living at Summerhill, The Macmillan Co., New York, NY

The New York I Know (with Marya Mannes), Lippincott Publishing, NY

In his sixth book Glorious Days and Nights: A Jazz Memoir Herb Snitzer looks back on a career of photographing jazz musicians.

After graduation from the University of the Arts (Philadelphia College of Art), Snitzer, who was born in 1932, headed for New York.

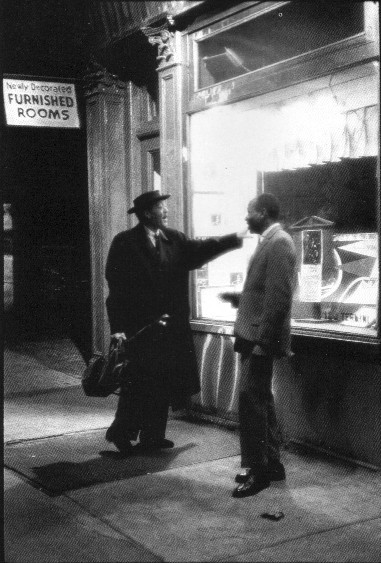

One of his first free lance assignments was to cover the legendary, tenor sax player, Lester Young, at the Five Spot Café, in 1958. Shooting at night with available light he created an enduring image of Young, holding his instrument case, wearing his signature porkpie hat. The scene is backlit by a storefront and there is a sign projecting from the building that reads “Newly Decorated Furnished Rooms.” The musician with arm outstretched is pointing to something while engaged in a conversation with an unidentified man.

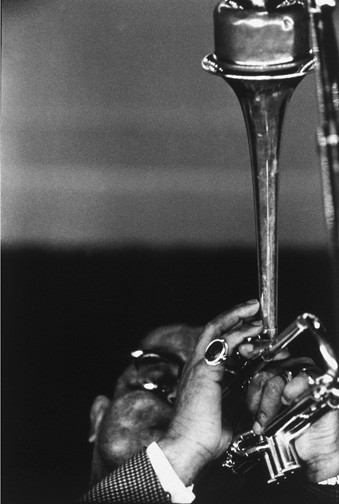

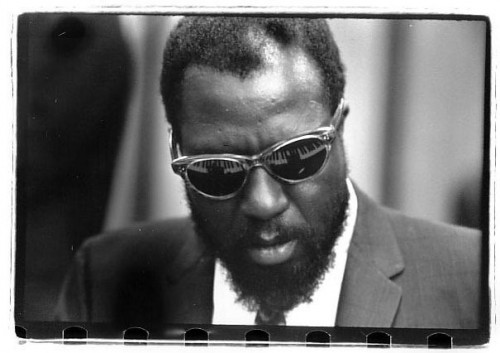

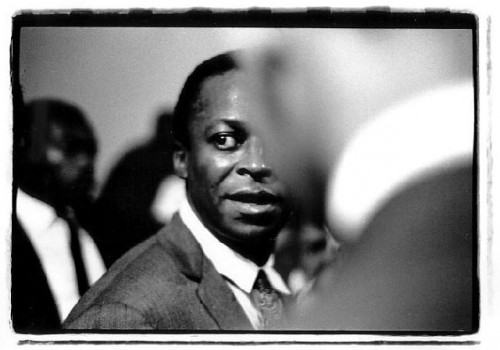

With this earliest image Snitzer launched a career and also, in embryo, established a style that identifies many of the key works among the 84 photographs selected for the book. While there are many studies of musicians in performance he sought out access back stage, on busses, in bars and hotels. As much as possible he attempted to get close and personal. There are many intimate portraits that compellingly convey trust as well as proximity.

As the subtitle of the book conveys this reaches beyond a portfolio of beautiful images of now mostly deceased masters of the art form. In the accompanying 42 page text Snitzer relates a life depicting the jazz world to which he had unique and often challenging access.

From the earliest accounts of his high school and art school years, to the first tentative involvement with the jazz world, there are frequent and often awkward, self conscious references to race. As the boyish looking, slightly built son of Jewish immigrants, with little or no understanding of the life of an artist, he relates making his way as an empathetic white man in the milieu of mostly black artists.

It is a familiar narrative that conflates with the entire history of the medium. Ironically, the first jazz recordings, by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, were made by a group of white musicians. The first black singer to record, Mamie Smith, did so on the spur of the moment because Sophie Tucker did not show up for the scheduled session.

There has been a curious literature as hip whites have attempted to convey their experiences of black culture. An early classic was written by a minor, Jewish player, Mezz Mezzrow “Really the Blues.” It is a fascinating book largely written in the slang invented by black musicians. Curiously, in that tradition, Snitzer’s book even contains a glossary of terms. One assumes that only hipsters would read his book. As we say “Never hip a square.” Even Norman Mailer took a stab at the genre with his now terribly dated essay “The White Negro.”

Being involved in the jazz world, however, goes beyond being hip to the jive. For many white jazz musicians it has also meant acquiring the bad habits and pitfalls of a rough life on the road. For a generation of young emulators “Blowing like Bird” meant getting strung out on smack. Snitzer touches on the problems of Stan Getz and Chet Baker to mention but a couple. While he relates hanging with Monk, and getting badly beaten by him at table tennis, he fails to mention his daily pharmacology.

In many ways the text of this fine and riveting book is every bit as involving as the meticulously selected set of images. There is a lot of edge and poignant insight to the narrative of a man determined to record a world and lifestyle to which he had a backstage pass.

When entering into the world of others it is best to have credentials. The ever present camera was a means of access. It gave the excuse and reason to be there and tolerated. Add to that representing a noted publication Metronome, first as a contributor and eventually, in its final phase, as co-editor with Dan Morgenstern. The jazz critic has provided a brief afterward to the book. It is interesting to learn that while Metronome struggled to find readers and sell subscriptions, Downbeat, had no such issues. It was a tax write off for a publisher with lucrative investments.

There are insights to the struggles of Metronome. Initially it primarily covered the mostly white big bands. Snitzer conveys trying to cover the emerging black performers he was listening to in the New York club scene like Miles, Trane, Monk, Ornette and Cecil.

Oops, left out the last names. But as Billie sang “Don’t explain.”

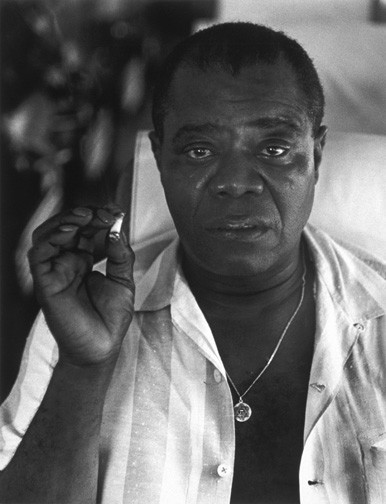

Like how Snitzer conveys that white folks referred to Louis Armstrong as Satchmo. But those who knew him called him Pops. He got to hang out and related a hilarious tale of when Pops and Trummy Young were jiving in front of Armstrong’s house. With endearing charm Snitzer informs us that he hadn’t a clue what they were talking about. Which cracked up the musicians.

Similarly Snitzer found Dizzy Gillespie anything but. He refused to use that nickname and addressed the musician with his own nick name “J.B.” after his name John Birks. The book is full of such interesting nuances. Like how and why Pop wore a Star of David medallion. Read the book and find out about it.

This is a wonderful and warm narrative about riding the bus to gigs with Duke and Pops. Or getting jived and abused by the diva, Nina Simone, whom everyone knows was a piece of work. She would, from time to time, cuss out her audiences. Snitzer adored her, tried to see where she was coming from, and worshiped her as an artist. A very troubled one.

Hanging out in the jazz world entails taking a lot of heat and abuse.

Over dinner at the Half Shell, just up the street from the former Jazz Workshop, the blind musician, Roland Rahsaan Kirk, was on a screed. While a couple of the guys from the band fell off their chairs laughing Kirk went on a tirade about the muttthafuggin white jazz critics. I took notes and picked up the check. It just came with the territory.

This book resonates with me. It also inspired awe of so many great performers that I never got to hear or hang out with. And those gorgeous images. They would give any fellow artist fits of envy.

One photo in particular struck me. It is not the most compelling. The caption states “Woody Herman and the saxophone section, Beverly, Ma, 1983.” That’s the day I met Herb at Sandy’s Jazz Revival. I have a thick file of slides and negatives from that gig.

There was a party for Herman and his all star band hosted by a fan who was small, dressed like Sergeant Pepper, wore a wig, didn’t smoke, and lived in a huge house. In the living room there was a grand piano and an expensive drum kit with too many Zildjian cymbals. His fantasy was playing for a jam session with all those incredible musicians.

On the walls and set up on decorator, Plexiglas easels were numerous kitsch prints of Leroy Nieman then famous for his splashy Playboy illustrations. Everything about that experience reeked of money and bad taste. The musicians vacuumed the spread, lapped up the booze, and had a great time hanging out.

Later, the host got caught up in a scam that made the front page. And the house burned down. Probably heavily insured. Destroying all those Niemans.

The jazz life.

Solid.

Hey Herb, I dig your book. Thanks for the memories.