Dishwasher Dialogues Folly and Madness in Theatre

Blacck to Black

By: Greg Ligbht and Rafael Mahdavi - Jan 29, 2026

Dishwasher Dialogues Folly and Madness in Theatre

Black to Black

Rafael: Then there was the play, Black to Black. Leroy helped finance that from his winnings at the racetrack. He must have won big that first time. He gave us a wad of bills.

Greg: I don’t think I knew that a gambling habit was behind the funds Leroy gave me with this play. Although, in retrospect, support from winnings at the track is more than apt. These projects of ours were all shots in the dark. Leroy appreciated the risk, the craziness, the art of what we were doing. He could relate. I think it was him through and through.

Rafael: The creative life. The biggest gamble. The odds are slim. We found a basement where we rehearsed near the Place Clichy, behind the Cafe Wepler. It was a kind neighbourhood, where socialist dreams met hopeful, poor creators, and wannabe bourgeois folk. I think Henry Miller mentions Cafe Wepler in his book Quiet Days in Clichy.

Greg: I remember it was a large, empty, decrepit space owned or leased by a group of young French artists and actors. They were a little bit older than us and were working in other parts of the building. The space hadn’t been used in a long while and the first day we spent the whole morning picking up and sweeping the litter and dust left by previous tenants. After a few hours, I asked one of the French artists if they had any large bags which we could put all the garbage into. He said he would buy the bags across the street and be right back. I remember waiting and waiting and wondering where he could possibly have gotten to. Finally, I went out into the street to find him. Across the street was a bistro. I went in and there he was sitting at a table with his colleagues having a full lunch.

It was at that moment that I learned the culture of French meals. Two hours in the middle of the day to talk and drink and enjoy one’s food. No matter what the urgency. Nothing is more urgent than a good meal. Certainly not bagging up rubbish. I was astounded at the time and feeling more than a bit irritated. Eventually, I came to appreciate this lunchtime break. During our rehearsals, we soon began to frequent the cheaper workmen’s cafés in the area and enjoyed some of that same experience.

Rafael: Do you recall there was a little restaurant called Casa Miguel near Chez Haynes? It was run by a Spanish anarchist refugee from the Spanish Civil War, and you paid what you could afford for your meal. The Guinness Book of World Records called it at the time the cheapest restaurant in the world. Quite amazing.

Greg: I do remember it. They served a full French meal with all the courses for 4 or 5 francs.

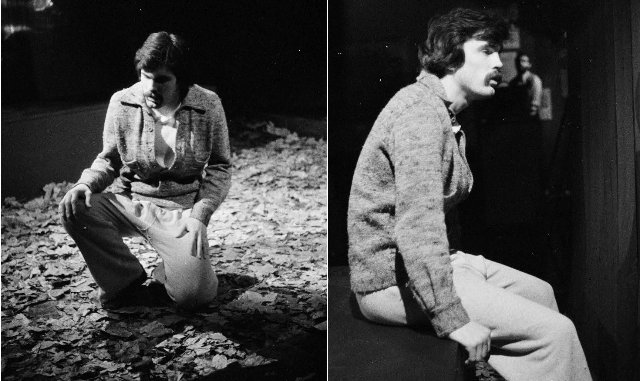

Rafael: But back to the play. We scrounged up bits and pieces from dumpsites and empty lots for the stage set. Laura took photos, which came in handy since they provided a record of the permutations of our rehearsal spaces and the set too. We did this play with zero money, a play put on with leftovers. We created something with stuff that people threw away, death come to life again, resurrection. After all, isn’t poetry made with leftovers?

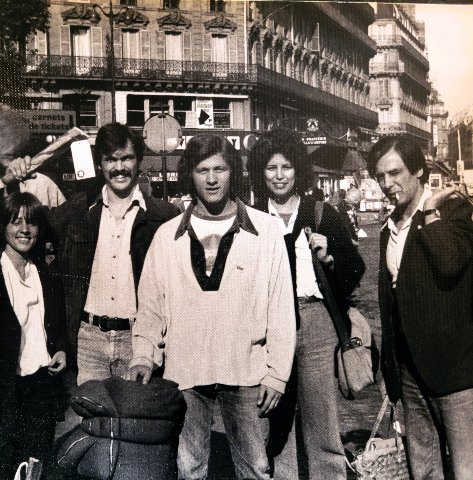

Greg: The words for the play certainly were. Leftovers from some of my poems. And, of course, the set was. And, maybe, we were also leftovers as well. Leftover from whichever country or countries we came from. Chez Haynes was a curious community of young, mainly English-speaking, seekers, residing in Paris for all those reasons that inspire young people to see and experience and ride along with whatever is happening. We came from different backgrounds with different dreams and different interests and different talents but also a knack for doing things. When an opportunity emerged, we were willing to start sharing and connecting and throwing stuff into the cauldron. We provided each other with a ready ear for ideas with non-threatening feedback. I think we were all fortunate to have found each other.

By this time, Molly and Tex, new members of the Chez Haynes crew, had joined the Black to Black production. Molly took over directing the piece. She had trained as a dancer and somewhere along the way had acquired theatre experience. She had experience directing actors in New York. I think she thought my theatre experiments were nuts, but she was also happy to go along with it all, and she added immensely to my performance. Later, she taught a dance course at the American Center, and I remember assisting her on a terrific dance piece which she designed and performed to Philip Glass music. And then there was Tex, who had no theatre experience that I knew of, but was smart, energetic, and happy to go wherever the set, lighting and stage management needed to go. He had also taken over Thomas’ room next to me on the fifth-floor walk-up. The one with the shower stall. And you managed the publicity. Which meant photography.

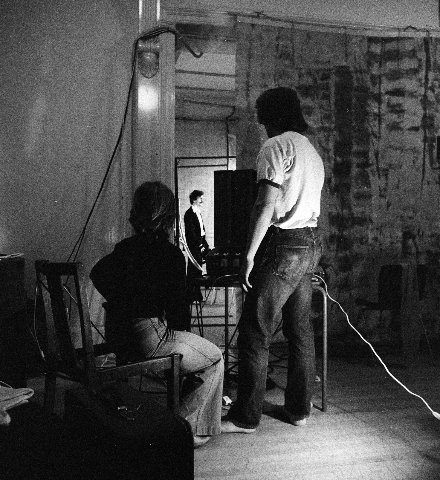

Rafael: Here, I want to say a few words again about taking photos in those days. Today people use their cell phone, and the pictures are good. They have little idea of what it meant to take pictures at that time. You had to use black and white 35 mm negative film. If you wanted color indoors, you had to have special lighting. We developed the negatives, then with a magnifying glass we chose the best images from the contact sheet and had them printed up. Later, as I said earlier, I set up my own darkroom.

Greg: I remember making those contact sheets in the darkroom. We poured over them, looking for the exact image that worked for our purposes. We did this almost from the beginning. For multiple shows. There is even a photo of the obelisk in my sitting room. We had cleared the room, filled it with dead leaves, and placed this obelisk next to the window. Don’t ask me why. Maybe the leaves foreshadowed the rags to come.

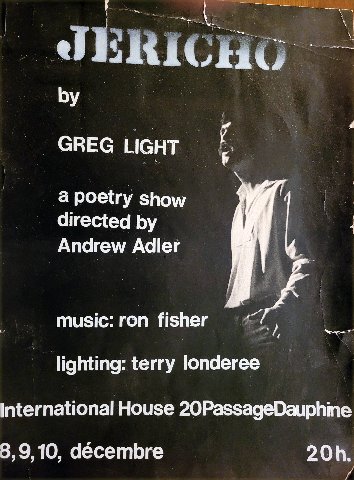

Greg: Black to Black grew out of the early performances of my Jericho poems at the International House, at 20 Passage Dauphine in Paris and at the Centre Culturel in St. Gratien, another Parisian suburb. I have little memory of how those shows came about and who was involved other than working with you on the photographic work.

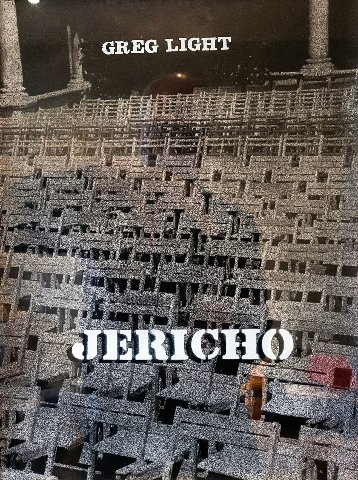

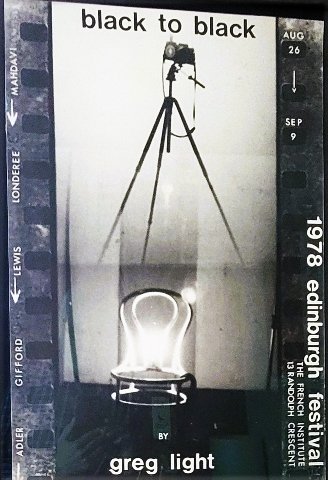

I do remember that the audiences were mainly French and working with a completely English text was unsatisfying. I gradually began breaking the poems down in rehearsals, improvisation and repetition of lines and movement, adding odd props—including a large electric typewriter and a camera on a tripod—so the text could all fit onto one page, be translated and put in the program. That is how Black to Black developed, the title coming from one of the Jericho poems. We were going to publish those poems in a small book, very similar to Tundra in look. It was a kind of sequel although very different poetically. You had designed the cover, with similar lettering over a photograph you had taken of what looked like an ancient Greek Theatre full of hundreds of empty fold-up chairs. But then money and events overtook us. It was not published.

Rafael: Getting the Black to Black play script photocopied wasn’t that easy, there weren’t that many copy machines around, and it was expensive to make copies.

Greg: I didn’t need many copies to begin with as I had shortened it to fit on one page which was translated into French. We handed out both the English and French versions (and eventually German, as well) to audience members. The publicity package primarily consisted of photographs you had developed. Even the shortened text was photographed.

Rafael: We got the package together, wrote a cover letter, and sent the envelope to the Edinburgh Theatre Festival. None of us believed anything would come of it, from Edinburgh. But a few weeks later they wrote back, telling us your play Black to Black had been accepted. You had been given a place in a Fringe theatre. The Fringe was like Off-Broadway. No connections to cultural power brokers, no brown-nosing the right people. They had accepted us cold. Because your play was good!

For the record, for la petite histoire as the French say, I want to mention here that in 1966, when I was twenty and at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, I won a playwriting competition sponsored by the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. I went to some rehearsals of my play. But I never went to the opening night. My life was pretty rocky at the time, mainly because the U.S. Army was breathing down my neck. I fled to Paris. Recently I googled all this and to my great surprise, I could find no mention of any kind of this event at Ann Arbor.

Greg: Most of this memoir will not be verifiable by Google. All of it is from a time before Google. Before the days of endless ‘evidence’ and the historical ‘authority’ of the internet. Today, anything and everything can be found and verified whether it happened or not.

Rafael: The play’s title was The Joy Boys.

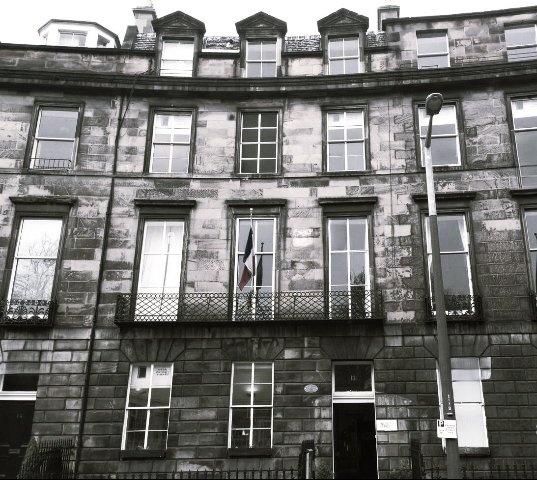

Greg: Prescient perhaps? Acceptance to the Fringe Festival back then was straightforward. If you could get a venue, you were in. Finding a decent venue was trickier. Ironically, it was the French aspect of our company and production that made it happen. Just as we created a press, we also created a little theatre company: Alliance Théâtrale—the name simply described this small alliance of different artists, actors, writers, dancers and technicians that connected in Paris at the time. I don’t remember the details, but I learned there was a French Institute in Edinburgh with a performance space, so we packed up all our materials including a short performance history (replete with photos) and presented ourselves to them as a bona fide French company. Back then the French Institute was on Randolph Crescent, a very central location in Edinburgh. I know they had a huge number of different events scheduled during the festival, but they accepted us and gave us a good time slot. I think we had to pay something for the space, but it couldn’t have worked out better. No highlevel cultural world connections were working behind the scenes. We just rolled the dice with the ideas and the art we had, and it paid off.

Rafael: Leroy was our Maecenas, our Pigalle patron of the arts, and of poets. Leroy allowed us to be dreamers, to follow our visions. I don’t know if he’d like to be compared to the famous Roman benefactor of poets.

Greg: Hard to say what he would think. But it sounds appropriate enough. He had been doing it for decades with musicians and now with us. His ‘patronage’—as unconventional as it was—cannot be underestimated. Not only did his restaurant connect us all, we always felt (but never knew for certain) that despite, or because of, the unique folly and madness that coursed through Leroy’s veins back then, deep down he appreciated, even cheered, the strange folly and madness coursing through ours. It’s why we worked there for as long as we did. To support and feed that folly. I know when I approached him for time off to go to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival—the biggest theatre festival in the world, bigger even than the Avignon Festival which he would have known of—his natural generosity and theatrical predisposition immediately surfaced.

Leroy: “I suppose you want some money for this production as well?” he said in his gruff, long-suffering voice.

Greg: “I’m not asking for that, but it would be nice,” I said, or something to that effect. I was genuinely taken aback.

Leroy: “Hmmmpfff” he grunted, or something to that effect, and stomped off.

Greg: But a few days later he handed me a wad of bills. I can’t remember how much he gave us, but the banknotes were of the 100-franc denomination not the 10-franc bills we were used to. The budget was certainly of the bargain-basement kind—we slept on somebody’s friend’s floor in a small flat not far from Edinburgh Castle. (I remember they had a three-year-old daughter who kept saying to Tex “you talk funny, you talk funny, you do” in her own very strong Scottish accent.) The train fare, shipment of the set and theatre hire required real money which Leroy’s contribution covered. We bundled everything together and left from Gare du Nord on a sunny afternoon.

Most importantly, Leroy let Molly, Tex and I take 10 days off in the middle of the summer tourist season to go up there. I am not sure he had thought it through. Not fully. Or maybe I was not entirely upfront that three of us were going. Whatever, he was irritated about the loss of staff when we returned. Maybe Don and the manageress had gotten their grumbles into his ear. The first day back, I remember him saying “I hope you had a good time up there. Go ahead and take another week off,” which he knew I could ill afford. Back then ‘no work-no pay’ was the rule for workers with no papers, and I had returned dead broke.

Rafael: For me, Leroy was always a bit of a mystery. Sure, I knew about parts of his life, but only parts, like snippets of a film. I never saw Leroy cry, for example. He had a diamond hard core. He’d seen too much, probably in the war in the Pacific. He could be very tough, especially on the waitresses, when he was drunk.

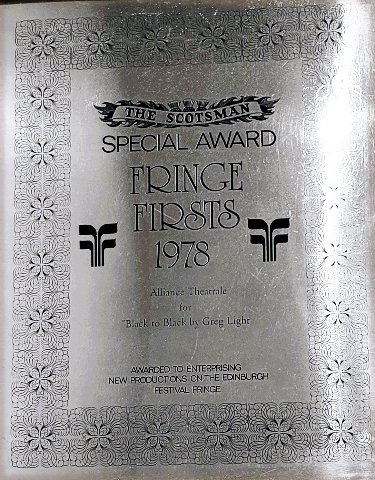

Greg: True. He had his dark side. Which was born somewhere we did not know or understand. The week following our return was tight. I guess Leroy felt I had a little lesson in life to learn. Baguettes and butter kept me alive. And 1F60-liter bottles of Ober Pils beer. But he didn’t fire me. Which he often did with staff at the drop of a hat. He had once fired me for a month (no memory why) but this time I escaped that fate. So, the lesson was not as bad as it could have been. He was clearly pleased, although never overtly so, with what we were all doing, and I think the fact that we won a coveted ‘Fringe First Award’ made him all the prouder.

Given its experimental nature, Black to Black had quite a run after Edinburgh, in a variety of different spaces and theatres in Paris; and then special invitations to festivals in Switzerland and Lyon. Then, along with One Day in May, it was eventually published in Toronto in a Canadian Playwright series.